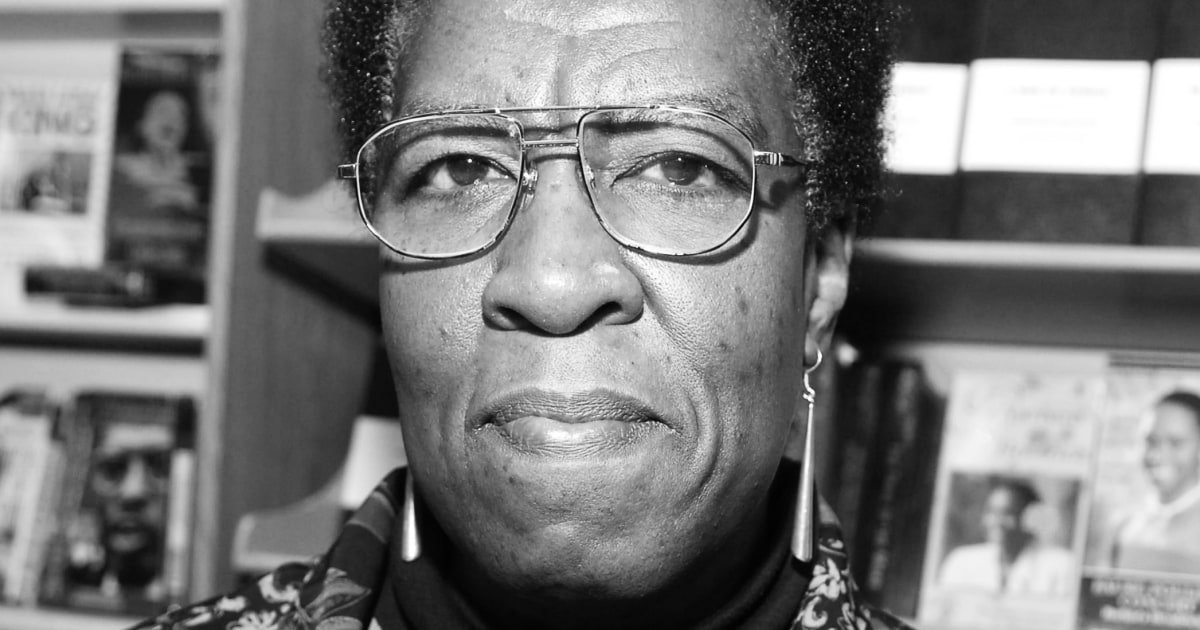

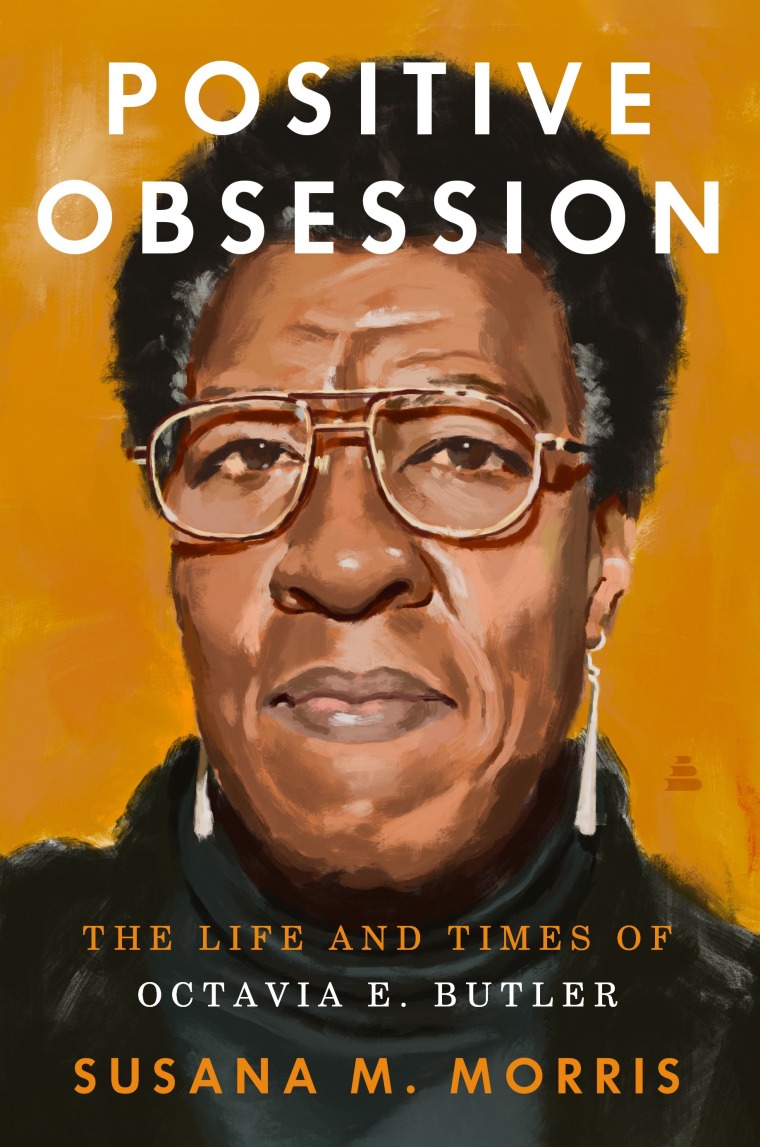

For science fiction novelist Pionera Octavia E. Butler, writing was more than a profession. It was a form of survival, resistance and reflection. In “positive obsession: the life and times of Octavia E. Butler”, the author and university professor Susana M. Morris shares the quiet but radical history of Butler’s life, revealing how the worlds he imagined were molded by which he often excluded her.

Going from a shy black girl, born in 1947 and raised with Jim Crow, to a literary icon, the path of Butler’s success was not linear. They told him not to dream but obtained a “real” job. While juggling with temperatures, financial anxiety and a society that resisted making space for her, Butler wrote literature that defined gender that has adapted to television and cinema in recent years, and has remained viral almost two decades after her death in 2006 in 58.

“Positive obsession”, called by a 1989 Essay by Butler, extracts from magazines, interviews and personal letters in Butler’s public archives to illuminate the forces that shape it, revealing an ambitious and meticulous writer.

During most of his career, Butler woke up before dawn to write for hours before what once called “many little horrible works.” While working in factories and warehouses, he washed the dishes, inspected the fries and made telemarketing calls, Butler conjured characters from his daily encounters.

Morris told NBC that by sharing Butler’s story, 19 years after his death, he hopes to inspire artists who do not believe they can afford to create time.

“In this economic system in which we are currently, we are so crunch trying to buy eggs or pay the rent,” said Morris, “sometimes we don’t even feel that we can access art for the good of art. But through all the tests and tribulations, I was accessing it.”

Butler’s newspapers show how writing was their way of withdrawing against racism, patriarchy and other norms that frustrated it and made her feel overlooked as a creative person and a public intellectual. She wrote because “she had to do it,” Morris writes. She put the pencil to the role to make sense of the world and speak again.

Beyond writing novels, Butler finally became known for his direct and evocative commitment to readers, whom he pressed to think about the world around them. He analyzed the dynamics of the real world and extrapolated them in prophetic and precious fiction. She wrote stories that seem to have become more popular as time has passed. His novel “Kindred” was reinvented in a television series in 2022, and authors John Jennings and Damian Duffy won a Hugo award in 2021 for their graphic novel reinventing their book “Parable of the Sower”.

In social networks, the “#Octaviaknew” trend captures the ominous ways in which their words resonate in the present issues such as climate change, inequality and politics. His ability, decades ago, conjuring how we live now gives Morris students a sense of connection with Butler’s work today.

In “Talents Stop”, published in 1998 and set in the 2020s, Butler presents a conservative presidential candidate that urges voters to join him in a project to “make the United States great.” The words on the page reverberated through the Morris classroom while teaching the book during Trump’s first presidency. That is why many readers think that Butler’s work was almost prophetic. “Psychic? Maybe not,” says Morris. “Prescient? Absolutely.”

Morris uses the 1987 story “The Evening and The Morning and the Night”, about a community dealing with a fictional genetic disorder, to talk to students about the marginalization of people with disabilities.

Butler’s short story of 1984 “Bloodchild” pushes readers to rethink gender, reproduction and family. “We are living at a time that demonizes the transercise,” said Morris. “But in ‘Bloodchild’, men lead babies. It complicates our idea of what the bodies are supposed to do.”

Butler’s fiction never floated reality. Confronted it. And continues to make readers question what they thought they understood. Although it is often filed as science fiction, Morris says that Butler’s work transcends the label, and instead classifies it as “speculative fiction.”

The immersive portrait of Morris can sometimes want to read Butler’s diary or listen to the most internal thoughts of a quiet person and sometimes lonely.

“She lived a life of the mind,” said Morris. From that life came the work formed by discipline, imagination and a kind of beautiful obsession, one that Morris expects others to reflect in their own lives.

“I hope that in this world he often lacks beauty,” said Morris, “that other people can see their example and find beauty in their own type of practice.”