There have been a flurry of announcements over the last few years by various multinational corporations (MNCs), either exiting Pakistan or significantly scaling down their operations here. Some of the prominent ones include Procter & Gamble, Shell, Caltex and Eli Lily, among others.

There has also been a significant slowdown in manufacturing activity, where more than half of products tracked by the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics through the Large Scale Manufacturing index have exhibited a median drop in production of 10 percent annually, over the last two years.

The gradual exodus of MNCs from Pakistan is a multifaceted affair that cannot be viewed through a mundane political lens. It is a mix of evolving strategies at a global or regional level for the respective entity, as well as a lacklustre economic and investment environment locally.

This write-up explores how the business models of MNCs have evolved over the years and how a shift in global trade is catalysing the exodus. There is also some introspection about how consistently elevated sovereign risk, and one of the more regressive taxation regimes in the world, has pushed any kind of formal business over the edge in Pakistan.

Even as the government touts policies to attract foreign investment, a number of multinational giants have been scaling back or exiting from Pakistan in recent times. What is going on here?

Is this the global economic environment at play or does this reflect deep fractures in the

country’s economic and regulatory framework? And can anything be done about it?

HISTORIC CONTEXT

Many MNCs that exist in developing markets were birthed by parent entities operating in those areas, mostly to serve the interests of colonial powers, or to consolidate the same.

As the sun started to set on colonialism after World War II, the emperor got new clothes, the MNC in this case, and they all got a makeover, trying to shy away from a troubled history. It can be an MNC that sold soaps and was notorious for operating palm plantations through bonded labour in Central Africa, or an MNC that basically led the Nazi war machine but now sells innocuous chemicals.

The history of MNCs has been dramatic and they have evolved with time. Only recently, after 355 years in operations, did the Hudson’s Bay Company shut down, after laying the foundations of Canada through trading fur across the Atlantic and eventually morphing into its largest landowner — only to be succeeded by a chain of department stores that were killed by e-commerce. They could survive multiple wars and the death of the Empire, but could not survive the post-pandemic transition to e-commerce shopping.

During the late 2000s, there was a similar mass exodus of financial institutions, not just from Pakistan but from other developing markets as well. This was largely due to higher compliance costs and the realisation that the only way to give economic returns to shareholders was to scale up and become one of the top five institutions in the respective country. It is only through scale that one can extract economic returns; without scale, they struggle and keep losing market share.

Many of these institutions survived the Opium Wars in China, and others, only to be forced to scale down by activist shareholders. Currently, only one bank from the times of the Empire continues to exist as a shell of its former self, while the rest have exited not just Pakistan but other emerging markets as well.

THE CHINESE CENTURY

The current wave of MNC exits can be partially attributed to the emergence of China as the world’s factory. This led to production of goods at a scale never seen before, and with scale comes lower cost. In emerging markets with relatively low household incomes, cost competitiveness remains critical and China provided the same.

Most MNCs operating in Pakistan, or those that have left, were largely involved in production of low value-added or primary products. Making diapers, washing detergent, or a basic generic drug does not require sophisticated knowledge or skill that cannot be replicated elsewhere. As China continued to compete on cost, local production became increasingly uncompetitive.

This led to the emergence of local brands that competed on price and made the overall competitive environment more intense. MNCs, instead of doubling down and attempting to scale, figured it might be easier to shut down operations and revert to a distribution model. Why bother manufacturing when you can import and trade the same? This is where the industrial policy of the country completely failed.

In many cases of consumer goods, some MNCs even produced advertisements at scale in Southeast Asia, assuming that all people of the Subcontinent look the same, subtly mocking actual paying consumers in the process. One can mock consumers only for so long and, in the case of primary products, consumers are often very price sensitive — a strong brand can compensate only to a certain extent for a price-conscious customer. As local brands started to prop up, the operating space for MNCs became further constrained, eventually leading to a point where the consumer gravitated towards local brands.

‘GREED IS GOOD’

The fictional character, Gordon Gekko, uttered the famous words “Greed is good” in the film Wall Street, while exemplifying the role of free markets in arriving at an optimal solution that benefits everyone and shareholders the most. In matters of capital allocation, shareholders lately are not swayed by emotional concepts such as patriotism or nationalism.

More recently, German engineering and chemical behemoths started moving out of Germany to the US and other jurisdictions where energy costs were lower — not because they were any less German, but because they were losing the competitive advantage provided by cheap Russian gas, which stopped following the initiation of the Russia-Ukraine war.

Similarly, a large number of financial institutions and energy companies moved their headquarters from the UK to other jurisdictions post-Brexit. A shareholder is more interested in how their economic returns can be maximised and makes decisions accordingly. Any other considerations may be noble but are noise at best. If a jurisdiction cannot provide the requisite economic returns, the MNC (or any rational business) will eventually shut down that business.

In the absence of perpetual state subsidies, or protection as a perpetual infant, which are hallmarks of economic policies in Pakistan, no business can survive without being competitive in the local environment.

INVEST IN PAKISTAN? WHY?

Now let’s turn our attention specifically to Pakistan’s economic environment.

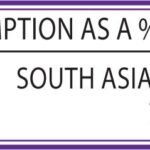

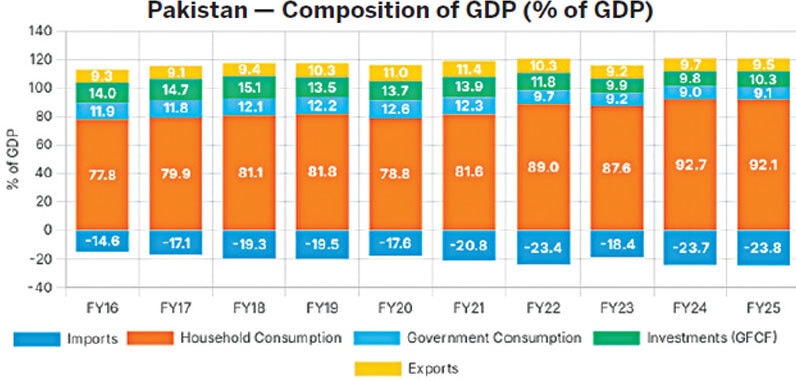

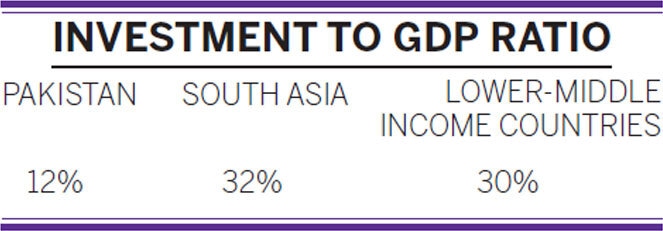

An economy’s gross domestic product (GDP) is a function of private consumption, government consumption, investments and net trade (more exports and fewer imports). The cumulative sum of all these factors leads to the calculation of GDP. Over the last 10 years, Pakistan has evolved into a consumption-oriented economy, wherein 99 percent of our GDP is essentially consumption.

To provide more context, for a typical lower middle-income economy, consumption makes up 81 percent of GDP, while the average for South Asia is 72 percent of GDP. This effectively means that we do not invest, produce, or export a lot — we just import and consume.

As we import more, we need more foreign currency, because that is how one buys imports, and when there isn’t much foreign currency available, this leads to the Pakistani rupee (PKR) losing its value, triggering a spurt of inflation before it settles, only for this Groundhog Day situation to repeat again. If saner heads do not prevail, we may see the same happening again within the next 18 months.

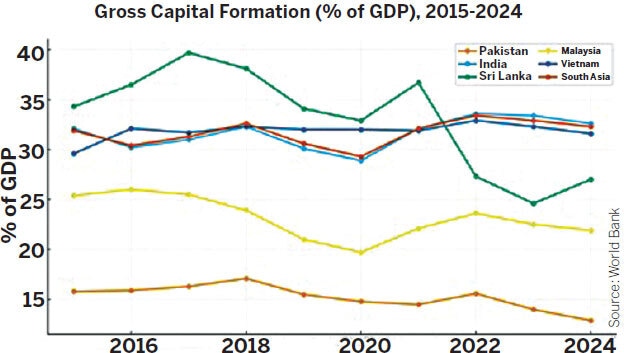

Before we can produce anything, we need to invest in productive capacity first. The Investment-to-GDP ratio for Pakistan has consistently remained in the range of 12 percent, while that for South Asia is 32 percent, and for lower middle-income countries, it is 30 percent. If Pakistan ever wants to be a middle-income country, it needs to achieve and maintain an Investment-to-GDP ratio in the range of 25-30 percent consistently.

It is only through investment in productive capacity that we can produce more, create more jobs and generate an economic spillover effect that leads to improved household incomes. No country has ever become a middle-income economy, or better, without investing in itself. There is literally no other way — it is simply not possible to become prosperous just through consumption.

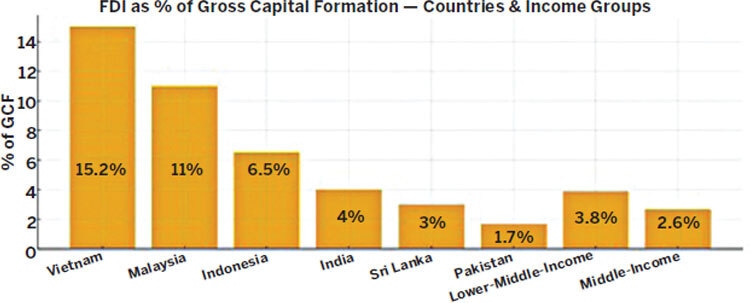

Investment in an economy is mostly a domestic affair, but we have it completely flipped. The government and its coterie of sycophants continue to beat the drums of foreign direct investment (FDI) without any introspection. For lower middle-income economies, FDI makes up around four percent of total investment, while for selected middle-income countries’ economies, it hovers in the range of five to 12 percent of total investment.

Only in the case of Vietnam is FDI maintained in the range of 12 percent. Effectively, domestic investment makes up more than 90 percent of investment across the board, a fact we completely ignore in the rush to sign off another Memorandum of Understanding (MoU), which is as good as exchanging business cards at a conference.

There is absolutely no reason why foreign capital would gravitate towards an economy where domestic investors are also reluctant to invest. Even when they do invest, they invest in non-productive segments, such as real-estate, largely due to an atrociously regressive taxation policy that penalises formal investment, production and value-added initiatives.

Digging deeper, investment is largely a function of savings, and given the state of financial exclusion and an inefficient taxation regime, there is little to no incentive to save through formal financial channels, resulting in a scenario where most savings find their way to inefficient avenues, such as real estate, stashing cash under the mattress, or gold.

None of these generate any worthwhile economic activity that can boost production. The investment problem cannot be solved without addressing the savings problem first. Policymakers currently continue to focus only on foreign direct investment, which does not solve any problem.

In a dysfunctional investment environment, the case to continue and expand operations in Pakistan remains weak. And it is further weakened through heightened sovereign risk, whether due to border skirmishes or the musical chairs that accompany leadership changes, eventually resulting in policy inconsistency.

THE COST OF DOING BUSINESS

The cost of doing business formally in Pakistan is much higher than the cost of doing business informally.

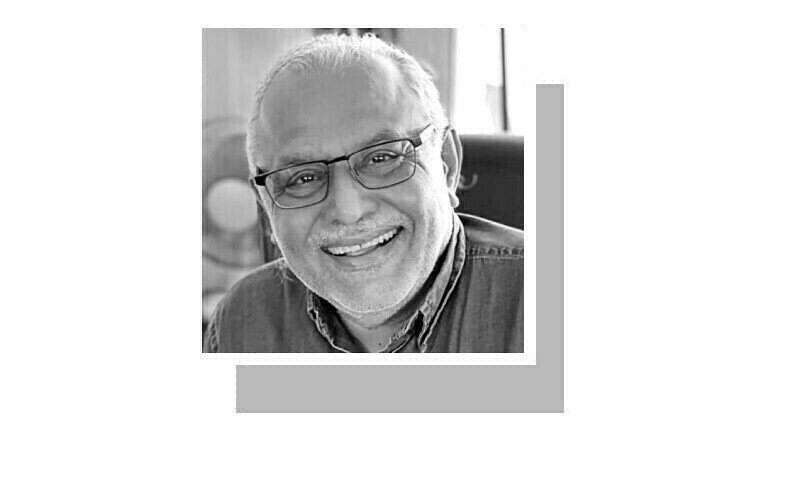

For example, an entity operating in the fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) space formally has to comply with all taxation and other financial or legal constraints. This can include a direct tax that can go as high as 40 percent, a contribution to the Workers’ Welfare Fund or Workers’ Profit Participation Fund that can exceed seven percent of Profit Before Tax, and a dividend tax of 15 percent. The effective tax an entity in the formal sphere pays exceeds 50 percent of its Profit Before Tax, even though the company is taking market risk.

Such an effective tax rate is much higher than in many developed economies. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) effective tax rate is 25.4 percent, while the highest is 34.8 percent in Columbia. In such a scenario, there is little reason for any entity to operate formally in an environment where half of its profitability is simply gobbled up by the State.

Similarly, any such company operating formally also has to comply with all Sales Tax requirements which, at 17 percent, are among the highest in the world, effectively discouraging more goods from coming into the taxation net. Meanwhile, any entity operating informally and selling smuggled goods can completely avoid paying this Sales Tax, effectively cannibalising the sales of the entity operating in the formal sphere.

Such a structure is so lopsided that an MNC operating formally and selling goods while paying all taxes may be cannibalised by the same goods it is selling, but which are either smuggled or imported at a lower tax rate, wherein the distributor and retailer can avoid paying Sales Tax through one way or another. Effectively, FMCG companies get cannibalised by their own products, due to an inefficient and perverse taxation regime.

DETERIORATING REAL INCOMES

Pakistan has been plagued by economic stagnation for the last seven years, if not more. Whenever an MNC enters a country, the expectation is that overall prosperity levels will gradually increase and so will household incomes. Due to economic stagnation, however, per capita income levels have actually gone down in American dollar terms. Moreover, adjusting for the tax burden, real income after tax has gone down even more.

Over a seven-year period, real income has effectively gone down by 45-50 percent and, after adjusting the same for taxes, it has gone down by more than 50 percent, with households across the spectrum (with the rare exception of those right at the top) losing half their disposable income.

It is estimated that expenditure on food made up 47 percent of the poorest 20 percent of households’ budget in 2017-18. Expenditure on food now makes up about 65 percent of the poorest 20 percent of households’ budget in 2024-25. This effectively means that more expenditure is being reallocated to meet basic existential needs, squeezing away demand from other areas, such as health and education. Effectively, there is less disposable income to go around, which means a lower demand for products.

For a market such as Pakistan, an MNC typically introduces the lowest-margin and most basic quality of products. As real income levels go down, so does demand for such products. The demand drops so much that entities have to resort to ‘shrinkflation’ — reducing the size of a product while not increasing prices. Shrinkflation implies moving down the value chain rather than going up — and that is a death knell for any growth-oriented entity.

The earlier notion that economic growth may lead to prosperity and higher income levels, eventually leading to demand for higher-margin and slightly more premium products, falls flat. Due to such a scenario, MNCs can see their revenue and profitability decline in American dollar terms while, at a shareholder level, this is seen as ineffective allocation of capital that can be reallocated elsewhere or returned to shareholders as dividends.

A THRIVING GREY MARKET

MNCs have to operate within a framework of compliance, even though their history may be dotted with all sorts of ethical discrepancies. As an example, in the case of petroleum products, there was a massive surge in the flow of gasoline and diesel from Pakistan’s western border through informal channels. The impact of such a flow led to a sharp reduction in the official sale of gasoline and diesel in 2022-23.

Officially, gasoline sales dropped by 20.6 percent, while diesel sales dropped by 37.1 percent in Sindh. We are specifically focusing on Sindh here because it provides granular details and is more transparent with public dissemination of data. The sale of petroleum products is a fairly stable metric — a significant drop implies substitution of the same with another product, or a product that is not captured by the formal economy.

As sales of smuggled petroleum products increased, it became increasingly difficult for MNCs to compete. Many petrol stations could simply blend formal and smuggled products, pretending nothing was happening, and capture the delta that emerged from taxes, which had to be paid on formal goods but not on smuggled products.

As such activity took hold, MNCs started losing market share, while reputational risk became ever more apparent, potentially leading to heavier penalties elsewhere. Inadvertently, in such a scenario, an exit from a market is better than losing market share and risking penalties in the process.

Similarly, Pakistan could never see the emergence of any serious MNC in the wholesale and retail space, largely because of the inability of MNCs to maintain multiple books of accounts to manage smuggling or goods trading in the informal economy. Local players can manage a profitable suite of formal and smuggled products, while MNCs would not be able to compete with such a product mix. In such an environment, where one is simply not able to compete because of a lopsided taxation environment, the market holds little promise for any serious growth.

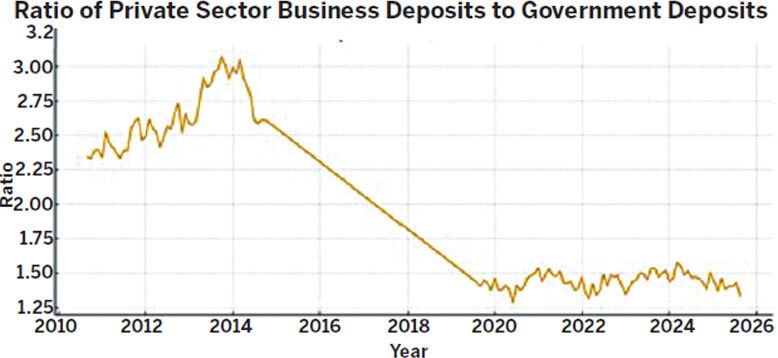

A pertinent metric of the prevalence of an informal economy is the ratio of Private Sector Business Deposits to Government Deposits, because a government will always have to use banking channels for its transactions, but private sector businesses can avoid formal channels. The ratio clearly demonstrates a significant drop, as the deposit growth of private sector businesses continued to lag behind government deposits, with most businesses preferring to operate in the grey, or as individuals to avoid taxation.

PRICE FIXING

The government has an obsession with fixing prices, a practice that has historically never worked, with thousands of years of economic history clearly demonstrating that the wisdom of policymakers cannot catch up to the invisible hand of the market. The government, and its different tentacles, has a habit of fixing prices, whether for medicine, electricity, gas, or something as mundane as milk or jalebis.

An economic environment where prices can be arbitrarily fixed leads to inefficient allocation of resources and does not allow businesses to compete in a fair environment. Fixing prices when costs increase results in losses for the producer, who then has to decide whether to continue with the business or completely change strategy.

The drop-off-a-cliff of the pharmaceutical industry, and its eventual plateauing, clearly demonstrates the same. Pharmaceutical production over the last three years has flat-lined and is much lower than in the years before that, even though the population continues to grow.

It can be seen in the production of tablets, syrups, capsules, injections and every other product. The demand continues to be there, but production has dropped as manufacturers moved towards a trading-oriented model. This is a classic case of shooting oneself in the foot: we destroy productive capacity through arbitrary pricing mechanisms and delayed drug approvals — and then we wonder why every pharmaceutical entity is packing up shop.

THE TAX ARBITRAGE

To keep it simple: if operating formally, an entity has to navigate the labyrinth of the tax code and incur additional compliance costs in managing it, while also having to increase the price of its final product. Meanwhile, if that product is competing with a product that can be smuggled or produced while evading taxes, the formally and honestly operating entity becomes uncompetitive, as its product is priced higher than others, resulting in erosion of market share.

An entity operating formally and complying with all regulatory requirements is actually priced out of the market. In such a scenario, there is no room for any sustainable growth, and companies eventually have to decide whether to operate formally and continue bleeding, or move towards the dark side.

HOW DO WE FIX THIS?

There is no magic bullet or magic pill. The road to reform is rocky and does not require an incessant number of conferences that do not solve any problem. It requires the will to solve the underlying economic problem, and that is a distortionary taxation and chaotic investment regime. The taxation structure needs to be fixed such that domestic investment is incentivised and risk-taking is rewarded rather than penalised.

This requires a significant reduction in corporate taxes and all other incidentals, whether that is super tax or other charges. It also requires a transition from the informal economy to the formal economy, and that can only happen with a massive reduction in currency in circulation and lower tax rates across the board. It is economically inefficient to operate formally in this economy; this is what needs to change.

The groupie behaviour to court foreign investors also needs to evolve. Solve problems for domestic investors first and foreign capital will follow. Capital follows risk-adjusted returns — it will gravitate towards whatever jurisdiction can provide more sustainable returns. The government should not be doing micro-interventions. It should be creating an enabling environment for competition to emerge and for attracting efficiency-seeking foreign direct investment. If we are being pushed to provide guaranteed returns for foreign capital, the battle is already lost at that point.

The government needs to step back from its obsessive-compulsive urge to set an arbitrary price for everything and creating unintended consequences in the process. Create an enabling environment and let the market operate. Creating an enabling environment is a long-drawn, boring process that cannot yield quick wins that can be celebrated with a half-page newspaper ad. This is where institutional development needs to happen, such that the enabling environment can sustain itself.

Savings need to be mobilised through formal financial infrastructure and reallocation of the same into non-productive areas needs to be penalised. It is easier to buy smuggled gold in Pakistan than to open a bank account or be part of the formal financial infrastructure — this is what needs to change.

None of the problems can be solved without solving for mobilisation of savings and redirecting the same towards productive enterprise. This is an economic problem and it needs to be addressed through economic tools rather than brute force, which never works on a long enough timeline.

The exodus of MNCs from Pakistan cannot be attributed to one specific issue but to a spectrum of issues that need to be addressed individually and as part of an economic reforms agenda. The first step in this journey is to accept that the wisdom of markets is far superior to the wisdom of policymakers. The sooner we accept this, the sooner we can start the reform journey.

The writer is a macroeconomist and professor of practice

at the Institute of Business Administration (IBA), Karachi.

He can be reached at ammar.habib@gmail.com

Published in Dawn, EOS, October 19th, 2025