Warning: This story discusses school violence, sexual assault and suicide.

When Trina Costantini-Powell began brainstorming what to feature in the 1970s room during her Ottawa high school’s centennial, she thought of Nixon, Trudeau and the Vietnam War.

But when she and other Glebe Collegiate Institute graduates gathered amid all the trophies and yearbooks in the school’s archive, they came upon something else behind a curtain: a framed pastel portrait of a hopeful-looking young woman who never made it to her own graduation.

That person, Costantini-Powell informed the group, was Kim Rabot.

That prompted some to ask: “Well, who is Kim Rabot?”

Fifty years ago this month, Rabot, only 17, was the first victim in a shocking and scarring series of events CBC is revisiting in an ongoing four-part series.

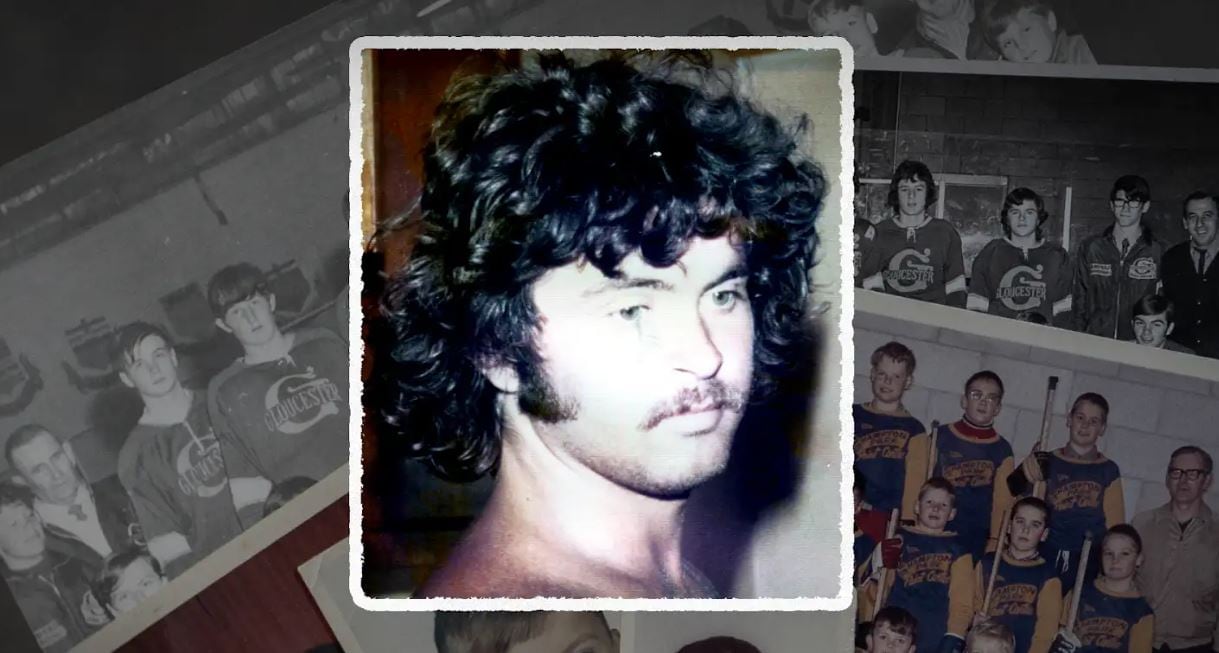

On Oct. 27, 1975, a student at St. Pius X High School raped and murdered Rabot at his home and went on to shoot up his St. Pius religion class, fatally wounding an 18-year-old classmate named Mark Hough and killing himself with the gun.

The murders and suicide sent shockwaves through the two schools and across the country. Canada’s firearms acquisition certificate system was introduced two years later.

But while the stories of some of the shooting survivors emerged over time, the same cannot be said for Rabot, whose brutal death was overshadowed by what was Canada’s second-ever high school shooting.

“My heart bleeds for what happened to Kim Rabot and the absolute torture her family and friends must continue to endure as the 50-year anniversary approaches,” says veteran RCMP member Al Hough, a cousin and close friend of victim Mark Hough.

As horrific as Rabot’s death was, there are people in Ottawa who for years have quietly ensured her memory is not forgotten.

As friend and Glebe classmate Fred May — who commissioned that portrait of Rabot — puts it: “There’s no way I can tolerate her just being remembered as a victim of a terrible, heinous crime.”

Part 2: The empty chair

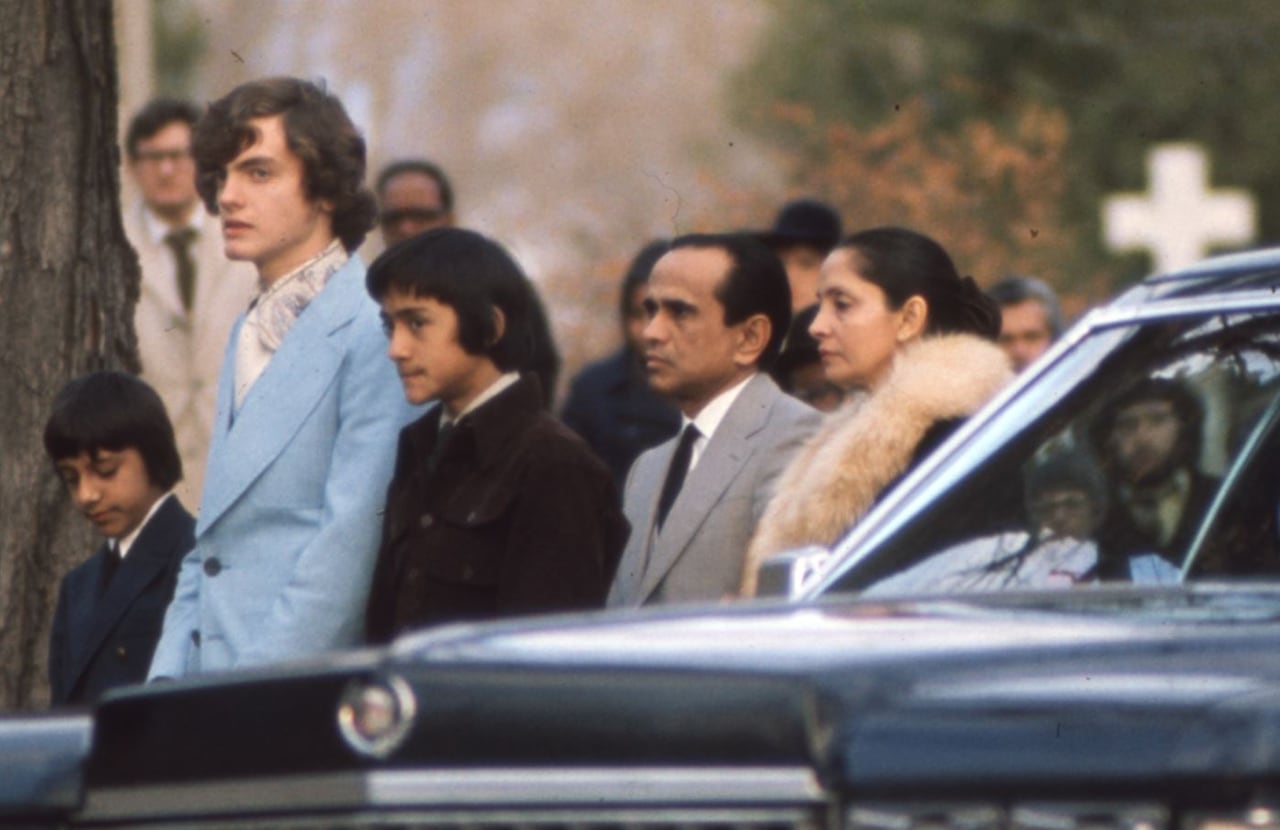

When Rabot’s light blue casket was lowered into the ground at Beechwood Cemetery three days after her death, May’s heart ached for her family.

“My God, you’ve come to this country to seek a better place, and this is what happens,” he recalls thinking.

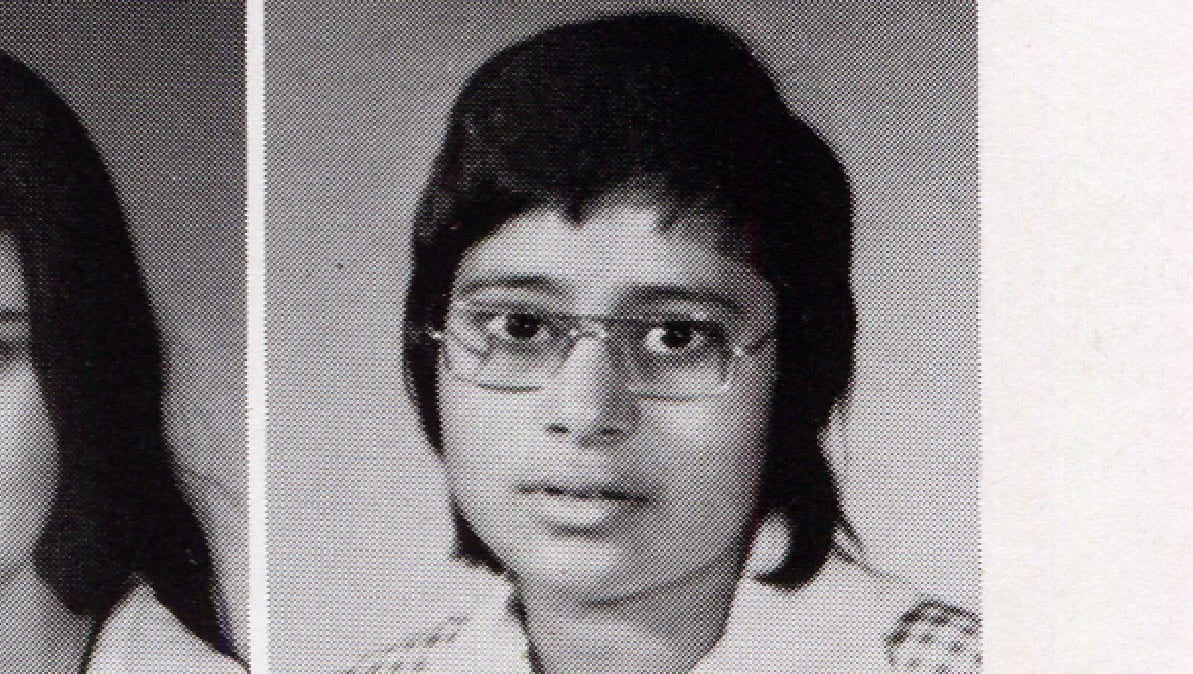

Rabot was born in London, England, in 1958 to parents who were from Sri Lanka (then known as Ceylon) and who emigrated to Canada as diplomats in 1967.

Her older sister, Sabina Lall, remembers Rabot as clever, intelligent, kind, helpful, loyal, a bit shy and “slightly nerdy.” She was an avid swimmer, played the flute and wanted to study to become a doctor.

The Rabot family lived in Old Ottawa South, just two blocks from Robert Poulin, the deeply troubled 18-year-old who killed Rabot. Rabot and Poulin’s school lives had briefly intersected when she spent part of her Grade 10 year at St. Pius, and the two families went to the same Roman Catholic church.

Fred May met Rabot in the fall of 1974 at Glebe Collegiate Institute when they became lab partners in Grade 12 chemistry class. Their teacher separated them because they got all the same answers right or wrong on tests, but it continued happening.

“We just clicked,” May says.

Rabot was a good listener with a nice laugh. She and May both played the flute, owned the same album of Bach renditions by Canadian jazz saxophonist and flutist Moe Koffman, and listened to music at her place.

She had a mischievious side too, May says.

“Sometimes she wouldn’t go to church, so she’d take the money she was given by her parents for the collection plate and go to the Dairy Queen instead.”

Costantini-Powell, who ultimately placed Rabot’s portrait in the 1970s room during Glebe’s 2022 centennial celebration, had a locker next to Rabot’s one year and got to know her a bit.

Rabot, though a year younger, was in some of Costantini-Powell’s classes.

“She was very smart — a very beautiful person inside and out,” Costantini-Powell says.

Another classmate, Louise Robb, was just getting to know Rabot when she was murdered.

“At my age 1760908946, she would have probably married, probably had kids, and been a retired citizen,” Robb says. “She missed out on all of that.”

Grieving in public

May didn’t learn that Rabot had died until the day after her murder and the shooting at St. Pius.

As the media soon pieced together, Poulin had set his house on fire after stabbing Rabot, then biked to his school.

At Rabot’s funeral, May remembers the look of “total devastation” on Rabot’s mother’s face.

Then, while the families were still fresh in their grief, came a “no holds barred” coroner’s inquest into the murders.

“[Sabina had] to get up and leave the room occasionally because it was just too much,” May says of the shocking details disclosed during the public inquest, held only one month after the murders.

John Rabot, one of Rabot’s younger brothers, testified that he was the last person to see his sister alive before Poulin approached them at their bus stop and convinced her to accompany him to his house.

Trina Costantini-Powell recounts another story about that day from her own brother, who also attended Glebe Collegiate and knew John Rabot.

“He and John were standing [on the third floor] and they could see the smoke rising,” she says. “He remembers John Rabot saying, ‘That looks like it’s in Ottawa South.’”

John Rabot died in 1994, predeceased by his sister and his mother, who died a couple years after her daughter’s murder.

LISTEN / More on the larger story from CBC’s This Is Ottawa podcast:

‘Not wanting to mention it’

After Kim Rabot’s death, May quit Glebe Collegiate because going back to class and seeing his friend’s empty chair “was really a bit much.”

He recalls the shock, disbelief and “not wanting to mention it for fear of upsetting people.”

“Here’s someone who had such possibilities in front of them, and they were all taken away in the world’s worst way,” May says.

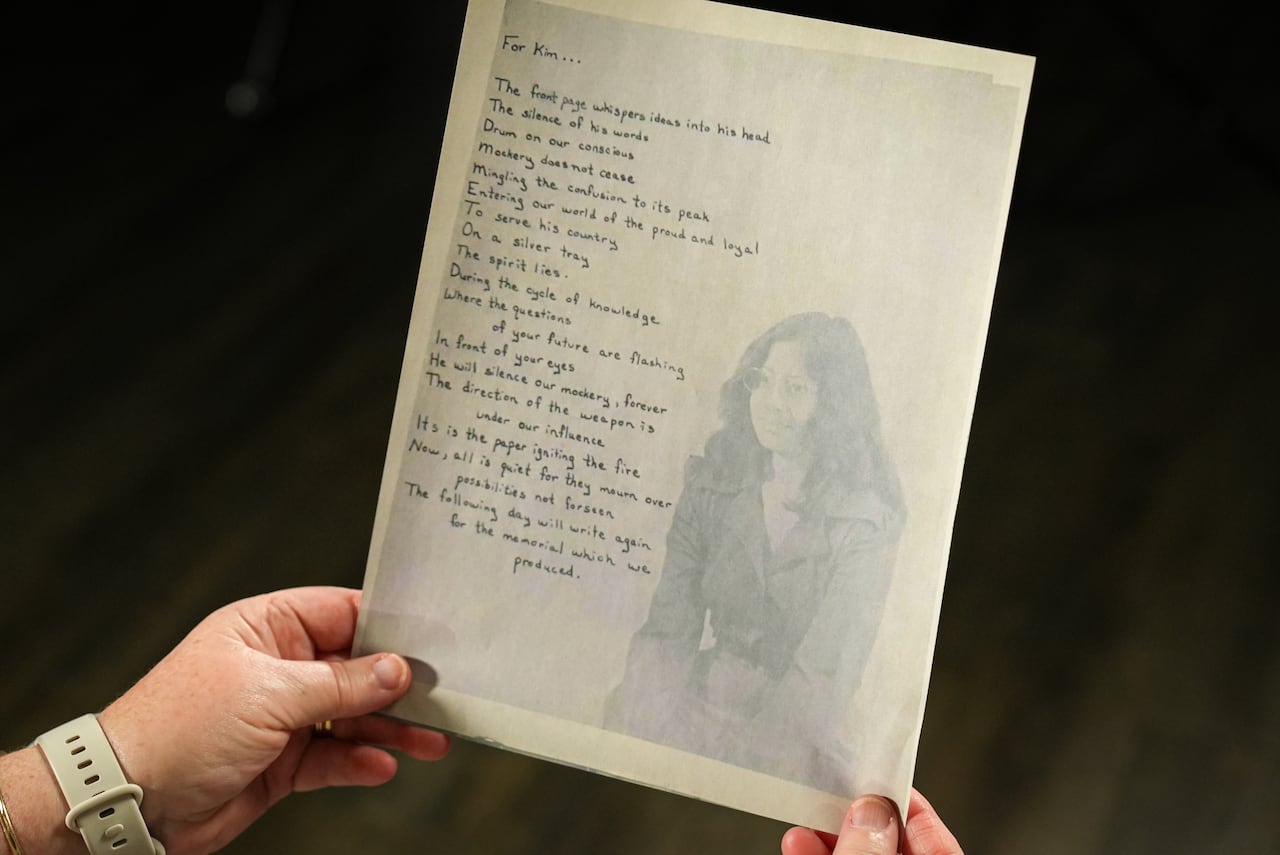

The school placed a tribute to Rabot in the 1976 yearbook. For Costantini-Powell, it’s still tough to read.

May had the portrait of Rabot commissioned that same year: one copy for him, one for Rabot’s boyfriend, and one for Rabot’s sister Sabina Lall.

The photo that inspired the painting was taken at school only weeks before her death, Lall says.

May couldn’t bear to look at his copy and put it away.

Many years later, however, it would play a huge role in helping keep Rabot’s spirit alive.

‘We can do something here’

It was in 1997, shortly after a major Ottawa Citizen retrospective on the shooting, that May felt like Rabot’s life was in danger of being forgotten.

He got together with a friend, Barbara McInnes of the Ottawa Community Foundation, who looked out the window wistfully and said, “I remember that day. We can do something here.”

Within two weeks, they had the legal framework for the Kim Rabot Memorial Fund. Three years after that, the fund had enough money to grant an award in Rabot’s name to a Glebe Collegiate graduate who, as the foundation describes it, honours Rabot by demonstrating “team spirit, dedication, and a strong work ethic.”

And that’s what’s happened for the last quarter-century.

At the end of each academic year, May sits amid the crowd of proud parents during the school’s commencement, watching as the portrait of Rabot sits either on stage or by a table greeting arrivals.

Twenty-nine recipients have come to learn about Rabot before being given the award.

“In some way, Kim is able to participate in the graduation she was robbed of,” May says.

This past June, in recognition of the 50th anniversary of her death, the school gave out two awards in Rabot’s honour.

Before the ceremony, May and a small gathering of people visited Rabot’s grave at Beechwood Cemetery.

“Kim,” May read aloud from a prepared statement, “I am sad to report that we still have hate with us in our world, and a terrible propensity for violence.

“But it is how we respond to hateful acts that counts too.”

This Oct. 27, Sabina Lall says her plans are the same as they’ve been for years.

She’ll pray and have a Jesuit mass for her sister, Mark Hough and Robert Poulin.

The Rabot family maintained a friendship with the Poulin family after the events of October 1975, Lall added in an email to CBC.

“Tragedies can bring about the courage to forgive, heal and unite our communities to make our community, country and the world a better place,” she wrote.

This story is the second in a four-part series.

Part 1 examined the events of Oct. 27, the coroner’s inquest, the debate about gun control and the experience of the Poulin family. Click to read it here.

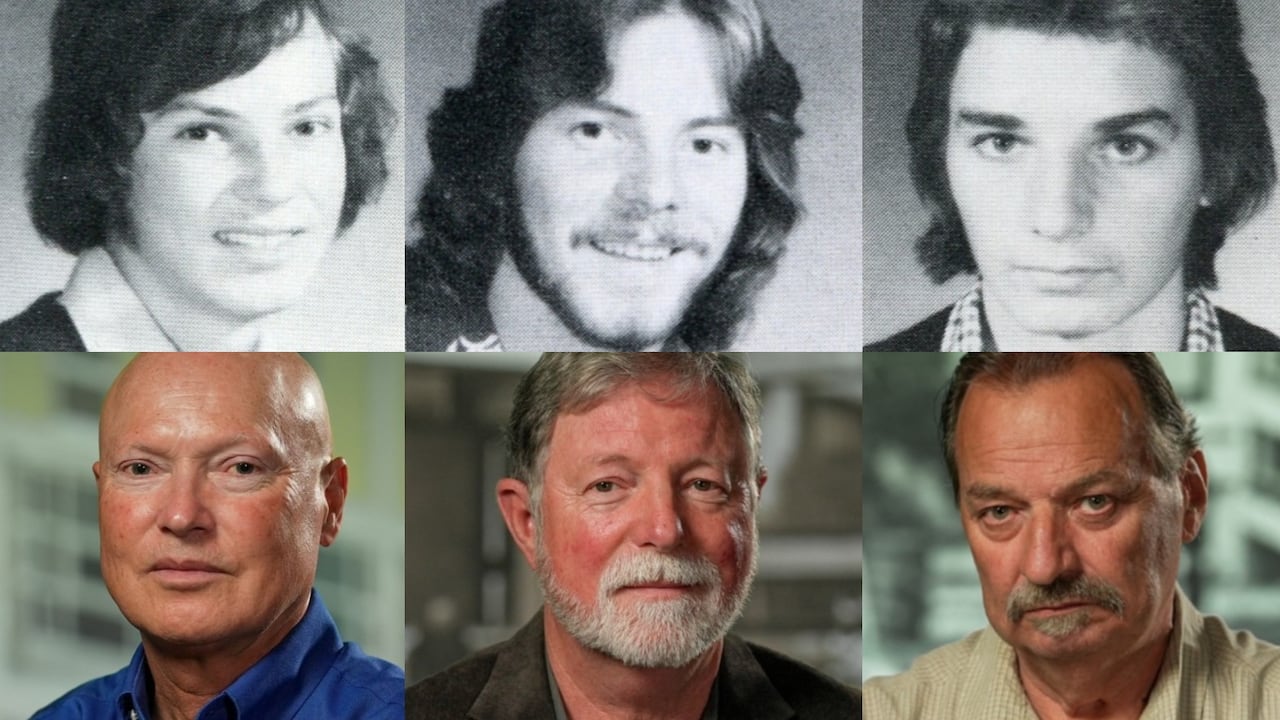

In October 1975, two Ottawa high schools were rocked by murders committed by a troubled student who then took his own life. As the anniversary approaches, CBC is looking back at the changes, both personal and societal, that took place in the event’s wake. (Videography and editing by Mathieu Deroy. Set design by Michel Aspirot.) (Thumbnail photo: City of Ottawa Archives, Ottawa Journal, 028395)

Part 3 on Oct. 23 will honour Mark Hough.

Part 4 on Oct. 26 will focus on the survivors of the St. Pius X High School shooting.

If you or someone you know is struggling, here’s where to look for help:

If you’re worried someone you know may be at risk of suicide, you should talk to them about it, says the Canadian Association for Suicide Prevention. Here are some warning signs:

- Suicidal thoughts.

- Substance use.

- Purposelessness.

- Anxiety.

- Feeling trapped.

- Hopelessness and helplessness.

- Withdrawal.

- Anger.

- Recklessness.

- Mood changes.

Producer: Jen Beard

Videography and editing: Mathieu Deroy

Set design: Michel Aspirot

Copy editing: Alistair Steele