Decades of stalled reform, donor dependency, and feminist fragmentation have left Pakistan’s women structurally excluded — and the Global Gender Gap Report simply holds up the mirror.

Every year, the World Economic Forum (WEF) publishes its Global Gender Gap Report, and every year Pakistan finds itself near the bottom. This year, however, Pakistan was ranked last — at 148th out of 148 countries. Instead of being seen as a predictable outcome of a historically entrenched pattern of gender inequality, the result triggered immediate defensiveness — not only from sections of the government and state but also from ‘progressives’ and ‘dissenters’.

Women-focused projects make up only 0.2 per cent of the Public Sector Development Programme (PSDP) in FY 2025–26, based on the Rs1 trillion federal development budget — a decline from previous years. Gender ‘tagged’ components still amount to just 0.57pc investment in female-centred education and health. The Pakistan Time Use Survey (TUS) has not been updated, and despite years of gender situational analyses and mapping by consultants, we still lack a cohesive or standardised nationwide, provincial, or district-level picture of gender gaps, let alone a domestic gender gap index.

Since the 1990s, and more intensely in the post-9/11 era, feminist discourse in Pakistan has often been mired in defensiveness around identities, culture, and religion. This dynamic has historically deflected critical feminist analysis from addressing urgent economic, legal, and material rights. Much of this pivot has come from within the feminist movement itself, especially from diaspora feminists who have enjoyed the freedoms of Western societies and whose activism remained limited to slogans and social media-led cancel politics.

Since 9/11, there has been a growing emphasis on cultural abstractions — such as the veil, Islamic feminism, queer identities, sexual harassment, and piety politics — at the expense of material and structural concerns. These debates eventually reached a turning point when pietist movements launched direct attacks on the more radical demands for sexual and gendered freedoms championed by the Aurat March in 2018. Despite injurious complaints about state biases (as if that was something new and original), the losses from academic and activist preoccupation with what became essentialist feminism, has eclipsed sustained engagement with systemic economic injustices, or the stagnant legal landscape for women — issues that had been the central focus before 9/11.

Generational shifts

The older generation of feminists/ male activists, many aligned with NGOs buoyed by Western funding, has retreated predictably — either retiring into WhatsApp politics or repeating projects funded by dull donors who dare not question or challenge the current authoritarian hybrid government. Meanwhile, the millennial feminists — many having migrated or married into Western societies — have distanced themselves from frontline activism, leaving a burden of performative activism and muddled political analysis to the Gen Z cohort. This generational shift has left the movement fragmented, with younger activists navigating a legacy of institutional fatigue and political paralysis, albeit far more bravely than their predecessors.

The failure to build solidarity on issues beyond identity politics has also contributed to a loss of feminist engagement with crucial regional and protest politics, such as Palestine or electoral justice. Notably, feminists’ unwillingness to support dissenting women within Imran Khan’s party, due to opposition to his authoritarianism, cost them a chance to defend women’s political participation and right to protest — a critical component in the WEF report.

Even today, when women’s reserved seats have effectively been usurped in the aftermath of the contested 2024 elections, there is a defeatist silence. This fracturing reveals a movement struggling to balance principled politics with pragmatic solidarity, ultimately weakening feminist influence on Pakistan’s broader socio-political trajectory.

Millennial accusations that any critical analysis of religious politics amounts to Islamophobia, cultural imperialism, or Western attempts to impose alien values have ultimately served the authoritarian state — more so than even the sycophantic liberals who once cozied up to General Musharraf. More recently, the same generation of the political left and right in Pakistan, unsurprisingly, have found themselves bedfellows amid the fresh surge of nationalism triggered by the latest conflict with India.

Despite their supposed ideological differences, both camps have rallied around nationalist rhetoric, often sidelining critical discourse on human rights, democratic accountability, and peace so as to present a unified front that prioritises national solidarity over substantive debate. Rarely have we seen this collaborative spirit on issues of underage marriage, property rights, minority persecution, or taxation. Yet, both ends repeat their collusive criticism of gender gap indices and secular feminist politics.

Valid critiques and local accountability

Dismissing the index without reflection is a missed opportunity. The WEF’s numbers may be imperfect, but they reflect real, measurable gaps in economic participation, political representation, health outcomes, and educational attainment. According to the Global Gender Gap Report 2025, Pakistan’s score for women’s economic participation and opportunity stands at a dismal 34.7pc (ranking only above Sudan and slightly below Iran, which, despite recent admiration among some Muslim men for its perceived female public visibility, scores only marginally higher at 34.9pc).

Pakistan’s female labour force participation stands at a meagre 22pc, and political empowerment is reflected by women holding only 20pc of parliamentary seats and zero ministerial roles. Health and survival disparities place Pakistan at 131st globally. Literacy rate for women is still under 50pc; science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) skills are non-existent/ not reported, and unmet family planning needs are high.

These stark numbers align with findings in research by several Pakistani feminists and experts who argue that economic frameworks systematically exclude gender concerns, failing to account for unpaid care work and women’s social reproduction roles. Feminist activist and former ombudsperson for Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Rakhshanda Naz, echoes this in her work dealing with women’s labour and landlessness, while others have highlighted unpaid domestic labour’s invisibility in policy and its impact on women’s empowerment.

Criticism of the WEF’s methodology is valid and has been pointed out. The index’s reliance on formal employment data often ignores the informal sector where many women work, and unpaid care labour is invisible in these statistics. Moreover, the one-size-fits-all global criteria fails to account for subnational disparities and intersecting identities such as class, ethnicity, and rural-urban divides.

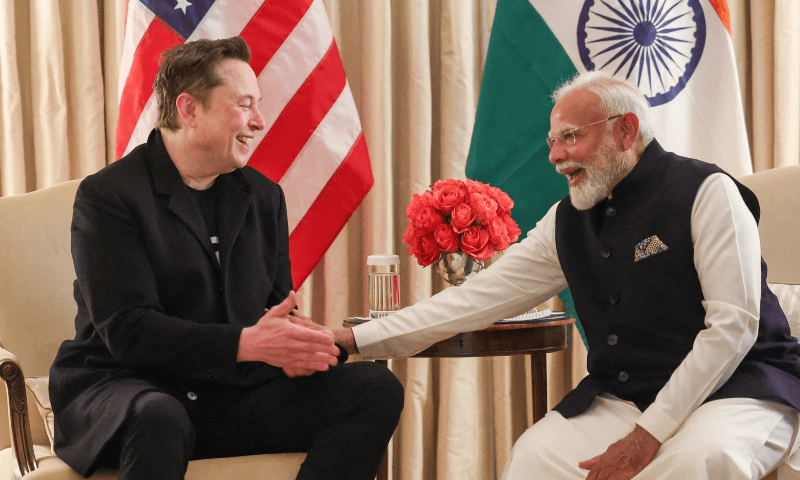

Researchers have demonstrated how federal budgets and resource allocations reproduce rather than reduce gender inequality. However, similar debates have taken place in India, ranked 131st, where scholars and policymakers critique the index’s limitations but also use it as a lever to improve gender policies. Pakistan must develop its own rigorous, transparent yardsticks instead of simply rejecting international benchmarks outright.

Logically, this should be the primary work of the National Commission on the Status of Women (NCSW), tasked with monitoring gender equality, but historically, the Commission has steered in an NGO mode and in fire-fighting as guided by UN funds and project directives, rather than charting a local feminist agenda. Increasingly, it shows a lack of political will or institutional power to confront entrenched patriarchy and leans towards governance feminism. It must cultivate a steel spine to report truthfully on Pakistan’s abysmal gender indicators, cutting through the political white noise and defensive posturing.

NGO-isation

Civil society too bears responsibility. Many NGOs chase donor funding by repeating workshops and empowerment programmes that produce visibility without systemic change. This numbers game of project cycles and reporting often prioritises metrics over meaningful transformation. Several researchers, such as Uzma Mushtaq, have pointed out the futility of project templates that do not aim for systemic transformation and, ironically, repeat the same ineffectual methodologies they criticise the WEF and government over.

Others, such as Nadia Naviwala, have highlighted how the aid economy in Pakistan has fostered an ecosystem of elite NGOs driven by donor-defined performance metrics that prioritise visibility over meaningful outcomes. This critique now extends to a new generation of women development practitioners working within the UN system and other donor agencies, whose emphasis on polished performativity is often reflected in ChatGPT-generated, design-heavy reports that mimic corporate aesthetics while evading substantive accountability.

The withdrawal or reduction of US Agency for International Development (USAID) funding should serve as a catalyst for NGO leadership to finally move from decades of critique to concrete action by formulating an independent, sustainable roadmap that is not donor-dependent but grounded in local economic priorities and long-term accountability. In any functioning corporation, such dismal outcomes as reflected starkly in Pakistan’s WEF gender ranking would warrant serious performance reviews, if not mass firings. Yet in the development sector, including donors, the impulse is to deflect blame onto the state and “culture” rather than interrogate internal failures.

Economic recovery

Pakistan’s low ranking is not an isolated anomaly. Bangladesh (ranked 24 — up by 75 places) leads the region, primarily due to over 22pc women in political ministerial positions over the last three years. Sri Lanka (130th), Nepal (121st), and even India (131st) outperform Pakistan significantly. Yet, Pakistan’s responses to these comparisons range from denial to conspiracy theories, instead of learning from regional successes.

My recent articles in Dawn Business and Dissent Today argue that economic reform in Pakistan must centre gender justice. Unfortunately, male economic elites who agree in principle, then retreat to the same traditional framework of women’s empowerment prescribed by NGO women leaders with no political depth or radical practical vision.

Most elite-led, infrastructure-heavy policies have historically excluded women and the informal economy. Gender-responsive recovery requires investment in care infrastructure, cash transfers, and reforms in discriminatory laws, especially around inheritance and citizenship.

Recently, the Government of Pakistan’s proposal to tax lavish weddings echoes feminist demands to redistribute economic resources and curb excessive consumption that entrenches inequality. But there is no group or collective devoted to such initiatives, as many stay on the safer, well-rehearsed but ineffectual project gravy train on violence against women and endless empowerment training.

Women are already ‘doing’ business in Pakistan, but they need direct access to technology, and bank account drives should be on a scale similar to voter registration campaigns. Women are already economic actors, but they require financial literacy and instruments, as well as issuance of national tax number (NTN) numbers. Women need banking services, but there has to be ease in opening bank accounts, and there must be customised schemes that provide easy loans and mortgages for women. The State Bank of Pakistan has to be committed to such policies.

Women also want to be in tech-related occupations but tend to be scared of it, and men seem to distrust women’s access to means of communication. A gendered communication strategy that closes these trust deficits is imperative.

Improvement in agricultural productivity is directly related to Pakistani women, since this is their main occupation — 67.91pc of all employed females work in this industry — but they are the lowest paid and earn less than half of the minimum wage. Only four out of 100 women qualified for agricultural loans, according to a 2018 UN report. There is no regulatory provision, outrage, or advocacy movement for such blatant violation and exploitation.

The political economy of marriage

Marriage in Pakistan is, unfortunately, not just a cultural tradition but a political and economic institution that often becomes central to women’s material inequality. Feminist scholar Saba Gul Khattak has critically examined how Pakistan’s political economy shapes gendered violence and structural inequality, with a focus on the intersections of gender, power, and economy. Amar Sindhu in Hyderabad and some activists of the Women’s Action Forum have curated their own records of cases and analysis, without donor support, over the connections of capitalism, violence, religious politics, marriage, and denial of property and economic opportunities against minorities and working-class women.

But we remain stuck on singular cases across provinces, and while ethnic discrimination is serious and odious, for feminists these issues are intersectional and collusive, and we cannot expect solutions to come from within these same sources of patriarchal control.

Why then are we investing so much hope, research resources, and activist energies on identity or ethnic-based struggles from our armchairs? Other such projects that invoke ‘culture’ as a vague obstacle to women’s equality do not specify that these are symptomatic, and so, they too do not tackle patriarchal structures that deny women property and financial rights.

I have argued, and continue to advocate, for policies like taxing weddings, not as a punitive measure but as a practical tool to address economic inequalities reproduced through marital rituals. Yet such taxation must be paired with supporting reforms to marital asset laws and inheritance to ensure women’s material equality within marriage.

This necessitates challenging the opposition to reforming and secularising family and inheritance laws, instead of re-interpretive efforts that have been exhausted, or shrugging in a defeatist manner over the Islamic nature of the state. This is not to suggest there is some simple correlation, but that it needs deeper scrutiny — Bangladesh has an extremely high rate of underage marriages, yet manages to score higher on wage equality, and as feminists there point out, such scores and technicalities do not translate into protection or justice for women, but at least some analytical clarity can emerge from in-depth study of such reports.

Pakistan’s family laws have seen incremental changes: judicial rulings and legislation like the Muslim Family Laws Ordinance (1961) and the Protection of Women (Criminal Laws Amendment) Act (2006) have acknowledged women’s rights to maintenance and inheritance. The Supreme Court, in cases such as Shahida Parveen v Federation of Pakistan (2016), has emphasised women’s rights to equitable support within marriage. However, the law still falls short of equalising marital assets or dismantling patriarchal control over family wealth.

Similarly, underage marriage is a topic of serious contestation but should not be treated by Unicef or scholars as isolated from property rights and marital assets. There needs to be a cohesive feminist strategy for such issues beyond incentivising education and health or looking for progressive religious edicts — these are material issues at stake. Addressing marriage as a political economy issue, and not merely as a cultural practice, is crucial for advancing women’s economic empowerment and material justice.

Engage, reform, and transform

Pakistan stands at a crossroads. It can either dismiss global gender indices as imperialist interference and technically flawed, or use them as tools to highlight failures and demand change. The WEF Gender Gap Index is not a flawless measure, but it is one of the few internationally comparable tools available to hold Pakistan accountable — to itself, at the very least.

To move beyond symbolic gestures and address its entrenched gender inequality, Pakistan must commit to structural reforms rather than rely on donor-driven optics or performative advocacy. This includes investment in public care infrastructure, enforcement of family laws that guarantee women’s financial rights, and the formal recognition of unpaid domestic and reproductive labour in national economic planning.

The political economy of marriage must be squarely addressed: taxing patriarchal consumption through levies on extravagant weddings and dowry-related expenditures, and reforming marital property regimes to ensure equitable division of assets upon divorce or widowhood. Not only would this redistribute wealth and reduce women’s economic dependency, it would also broaden the tax base — a crucial fiscal consideration in a debt-ridden economy.

As Zeenia Shaukat has argued, labour market reform is equally urgent. This means going beyond establishing clear benchmarks for wage equality and social protections in the agricultural and informal sectors, and setting up rigorous regulatory practices and maintaining and publishing these records.

Women must become owners of agricultural properties too, and only an agricultural tax can enable redistribution across gender and class. This must be scrutinised by the NCSW and feminist collectives. This is not just about the top percentage of women on boards or CEOs (which is important), but also documenting the progress on maternity leaves, sexual harassment policies, gender-equal wages, and the issues with vertical and horizontal segregation.

In manufacturing and services, women have very different challenges and experiences, and different sets of gender-based benchmarks need to be developed for them, while in the informal and domestic services sector, where a majority of working-class women are concentrated, a different set of standards and practices need to be regulated.

Social protection schemes must be universal, portable, and tailored to the realities of informal and seasonal work. They must not reinforce gender stereotypes or be made palatable to the comforts of patriarchs who guard the religious or political order. Gender-responsive budgeting should be institutionalised, with dedicated allocations for affordable housing for single women, legal aid, public transport, and health services. Political representation must not be selectively defended; feminists must stand by women across the ideological spectrum when their rights to participate are under threat.

Equally vital is a redirection of research and advocacy priorities. The absurd notion of men as heads of households needs to be redefined. The dominance of identity-focused agendas has often sidelined the urgent task of confronting material inequality. These can continue low-key, while feminist scholarship and development programming must now centre redistribution, land and labour rights, fiscal justice, and structural economic reform. Without this shift toward a material and political feminist economy, Pakistan’s gender gap rankings will continue to expose a state and society unwilling to deliver substantive equality.

Problem isn’t the score-card

Real progress demands not only that we critique the numbers but that we change the very systems and gender-blind policies that keep them stagnant. Most of all, political empowerment is where our index position was strongest due to reserved seats, and women politicians’ remarkable progress in leveraging these despite elite capture of national representation.

However, in the recent reserved seats case (Sunni Ittehad Council through its Chairman, Faisalabad and another v Election Commission of Pakistan through its Secretary, Islamabad and others, July 2024), a mockery has been made of this affirmative action policy, but complicated by the plaintiffs and their anti-feminist politics. This needs serious discussion among pro-democracy thinkers.

The NCSW must reclaim its mandate as a fearless watchdog. NGOs must shift from project cycles to structural advocacy. The government must adopt gender-responsive fiscal policies, including innovative measures, incentives, and protections for women, combined with family law reform — not selectively nor randomly.

Finally, Pakistani feminists and scholars must develop local yet rigorous metrics and frameworks to complement and contest global indexes. Until then, ignoring the mirror that the Gender Gap Index holds up will only delay the urgent reforms Pakistan’s women deserve.