“The problem with trials like this is the perception of victimization that strips them of their legitimacy,” said lawyer Basil Nabi Malik.

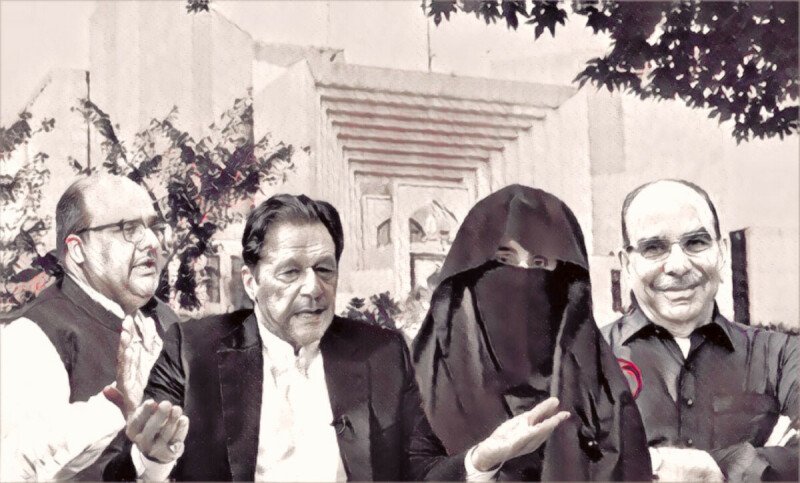

Former Prime Minister Imran Khan and his wife Bushra Bibi were sentenced on Friday to 14 and seven years in prison respectively in the £190 million Al-Qadir Trust case.

The verdict, announced by Judge Nasir Javed Rana in a makeshift courtroom in Adiala Jail, also imposed fines of Rs 1 million on Khan and Rs 500,000 on Bibi, with an additional six-month jail term for non-payment. .

The case, centered on allegations of embezzlement of funds returned to Pakistan by the United Kingdom, has suffered multiple delays in announcing the verdict, fueling speculation and controversy. With the verdict now finally in the field, here’s what the legal fraternity had to say about it.

What about the others?

For lawyer Abdul Moiz Jaferii, “of all the accusations against Imran Khan, this was the one that had substance.” He said there was “clearly an abuse of authority by the Prime Minister in allowing Malik Riaz’s illegitimate earnings, confiscated by the UK, to be used to satisfy a pre-existing sentence in the Supreme Court”.

“This was going to become part of the public fund and instead it sort of went back into Malik Riaz’s pocket.”

According to Jaferii, Imran Khan was the prime minister at the time and his cabinet approved such a transfer, albeit without any transparency. “It is not enough for him to justify this by stating that his motives were charitable and that the quid pro quo he received was for the betterment of the poor,” he said.

“However, even when there is a case to answer, the process and method adopted by the State and the judiciary reduce it to a farce. “The fact that nothing has been said or done about the main beneficiary, Malik Riaz, and the lack of explanation about the role of the others makes it very clear that this decision is motivated by factors other than the search for justice.”

Will history repeat itself?

According to lawyer Mirza Moiz Baig, the ruling shows that the PTI chief’s legal problems are far from over.

“While the Al-Qadir Trust case raises a number of questions about the former prime minister’s proximity to a real estate tycoon, the way the cabinet approved the transaction even when it was kept in the dark, and the conflict of interest, it would be negligent not to recognize that the standard of proof in criminal cases – beyond a reasonable doubt – is often submerged in cases involving opposition leaders,” Baig said.

“Given our history of verdicts not being approved when appealed to the higher courts, it would be interesting to see if this decision stands up to the scrutiny of the high court or if history will repeat itself,” he added.

What about the students?

Meanwhile, PTI lawyer Taimur Malik questioned the veracity of the verdict, adding that it would be ruled by the apex court on appeal. He stressed, however, that the federal government would have to ensure that “the academic status of Al Qadir Uni students is not affected.”

Perceptions matter

“The problem with trials like this is the perception of victimization that strips them of their legitimacy,” said lawyer Basil Nabil Malik. “It does not matter how true or correct the sentence or verdict is; The fact that it arises in a climate of fear, oppression and vendettas would ensure that the verdict, regardless of its reasoning, would be seen as motivated and unfair.”

“Perhaps that is why it is said that justice must not only be done, but it must be seen to be done,” he added.

Credibility at stake

For lawyer Ayman Zafar, these convictions are not a surprise: “after all, Pakistan has a well-documented tradition of ensuring that no elected leader emerges unscathed.”

“Disqualifications, imprisonments and forced exiles have become rituals, repeated with such precision that they now seem less like law enforcement and more like political choreography. “Our history is not one of stable government but of carefully curated instability, where leaders are prosecuted not for their crimes, but for their time in office.”

But beyond the predictability of all this, the real question remains: “Is there real substance behind this conviction, or is this just another round of political theater?” Zafar questioned. Legally, Khan and Bushra Bibi have the right to appeal to a higher court, where they can also ask for their sentences to be suspended. Whether the court grants relief will depend on the strength of the evidence, or lack thereof.

According to Zafar, the state must carefully watch what happens next. “If history is any indicator, the state’s response to any possible consequences will be as ill-conceived as the sentence itself,” he added.

“The handling of Khan’s appeal will be a test of judicial impartiality. Higher courts now have a choice: apply the law fairly or allow political expediency to dictate justice. The credibility of the legal system is at stake and the future of Pakistan as a functioning democracy depends on it.”

“Or maybe democracy was never really the plan to begin with,” he added.

Political maneuvers chapter

“The conviction of Imran Khan and Bushra Bibi feels less like justice and more like a plot twist prepared for political theater,” said lawyer Ahmad Maudood Ausaf.

“Judge Mian Saqib Nisar’s 2015 ruling (SCMR 1550) was clear: judgments must be handed down within 30 days of the conclusion of the hearing. However, this verdict played hide-and-seek, being postponed three times before finally landing (oddly) just a day after the PTI leaders met the Chief of Army Staff. Why the delays? Were they legal obstacles or a pause for political choreography? The moment raises surprise and stronger questions: Was justice really blind or spying over your shoulder for signs?

For Ausaf, the case itself sits on shaky ground. “The claim that funds meant for the State were redirected to a Supreme Court account through a hasty cabinet decision has no factual basis.”

“The UK National Crime Agency resolved its investigation into the Malik Riaz family, unfreezing their accounts and allowing funds to be transferred directly to an official SC account in Pakistan; no court ever declared that these funds were proceeds of crime or belonging to Pakistan. The land of Al-Qadir University? Purchased almost a year before the transfers, with no evidence of personal benefit to the trustees or financial loss to the state.”

According to Ausaf, “when verdicts are tied to speculative narratives rather than solid evidence, they threaten not only the accused but also the integrity of the judicial system itself.”

Can this trial, with its delays and dubious claims, be considered a fair trial under Article 10A?, he questioned. “The law promises transparency and impartiality, not verdicts that seem like the end of a political drama. “Without evidence of misappropriation or loss of state, this case risks being remembered as a chapter of political maneuvering rather than a triumph of justice.”