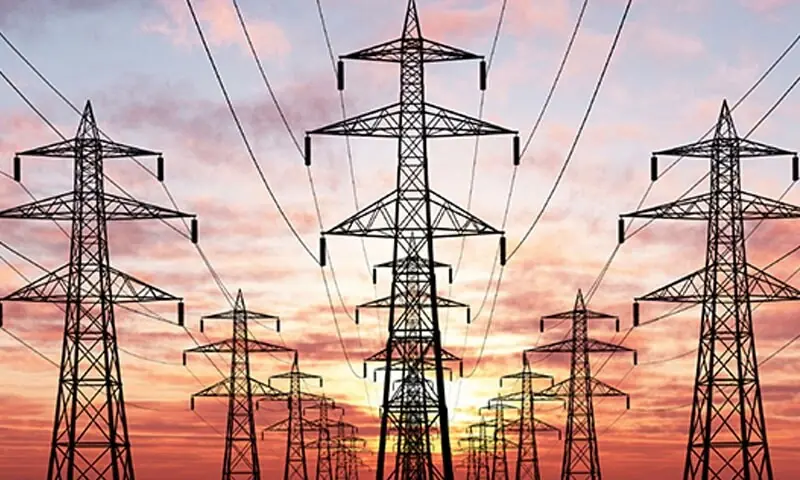

Islamabad: With limited progress in reforms and more than 4.6 billion accumulated responsibilities, Pakistan’s energy sector continues to forcing the economy, heavy for weak collections, robbery, poor infrastructure, market failures and market inefficiencies.

According to a detailed report by the International Finance Institute based in Washington (IIF), “taken together, there are about 4pc of the GDP of the debt derived from the energy sector. The repercussions reverberate throughout the economy, not only affect fiscal growth but also of growth, inflation, external balance and the financial sector.”

Circular debt has affected the country since 2006. Although successive governments have made periodic payments to relieve pressure, including a recent LS800B Liquidation, the flow of a new debt remains without control. As of June 2025, the circular debt stock stood at RS1.6tr (1.4pc of GDP), composed of another RS3TR (2.6pc of GDP) owed by energy producers to the oil and gas sector.

The report says that the debt has serious tax consequences. To contain high service costs, the government created Power Holding Limited (PHL), a special purpose vehicle forced to inject liquidity into the energy market, maintain the debt of the electricity sector and reduce financing costs. But by absorbing PHL liabilities in national books, the government effectively increased public debt and assumed additional risks.

IIF says that circular debt exceeds RS4.6tr, equal to 4pc of GDP, feeding tax risks and stagnant reforms

Currently, the circular debt represents approximately 2.2pc of total debt of the government, excluding the arrears of state generation companies to fuel suppliers. Together with energy subsidies, this has exerted persistent pressure on public finances, forcing the diversion of resources away from social programs, development and infrastructure expense.

Indirect effects

The IIF emphasized that the challenge extends far beyond fiscal management. On the financial side, loans through PHL have depended largely on national banks, contributing to the agglomeration of the private sector credit.

In the growth front, recurring energy cuts, often taxes in areas with poor recovery rates, interrupt industrial activity, investment and productivity, undermining competitiveness. At the same time, high electricity rates feed the main inflation, while a large dependence on imported fuel aggravates external imbalances, particularly during the depreciation episodes of acute rupe.

Political responses

Recognizing the seriousness of the problem, the authorities have introduced a series of measures. These include the approval of the Bilateral Competitive Negotiation Contracts (CTBCM) market, designed to break the monopoly of distribution companies (disc) by allowing large consumers to negotiate directly with energy producers.

Contracts with independent energy producers are displacing the “carrying or paying” model, by virtue of which payments are made regardless of consumption, to “carry and payment” the arrangements in which only energy consumed is paid. At the same time, electric tariffs have been raised, subsidies are being better directed and measures have been taken to address theft, improve invoices recoveries and reduce technical and distribution losses.

A gradual change towards national energy sources, such as hydroelectric energy and coal, is also underway in an effort to reduce dependence on imported fuels.

Still unsustainable

Despite these initiatives, the IIF observed that the reforms have not delivered significant improvements in sector performance. The recent drop in circular debt during fiscal year24/25 was largely due to a unique authorization that was made for commercial loans instead of structural solutions.

“As inefficiencies persist in distribution companies, T&D losses and poor collection rates, great bailouts are not a coherent or sustainable long -term strategy,” the report warned. He stressed that systematic inefficiencies remain deeply integrated in the energy sector, ensuring that the debt flow continues.

Reform deficit

The institute pointed out that many of the structural problems behind circular debt are well known but difficult to solve due to rooted institutional reluctance and aderred interests. The problem, he said, has become the “clearest example of why Pakistan’s reforms continue to fall short and why tax risks remain rooted.”

“Until this obstacle is overcome, circular debt will continue to weigh a lot in the economy, eroding the fiscal space, limiting the growth and instability of food,” he concluded.

Posted in Dawn, September 6, 2025