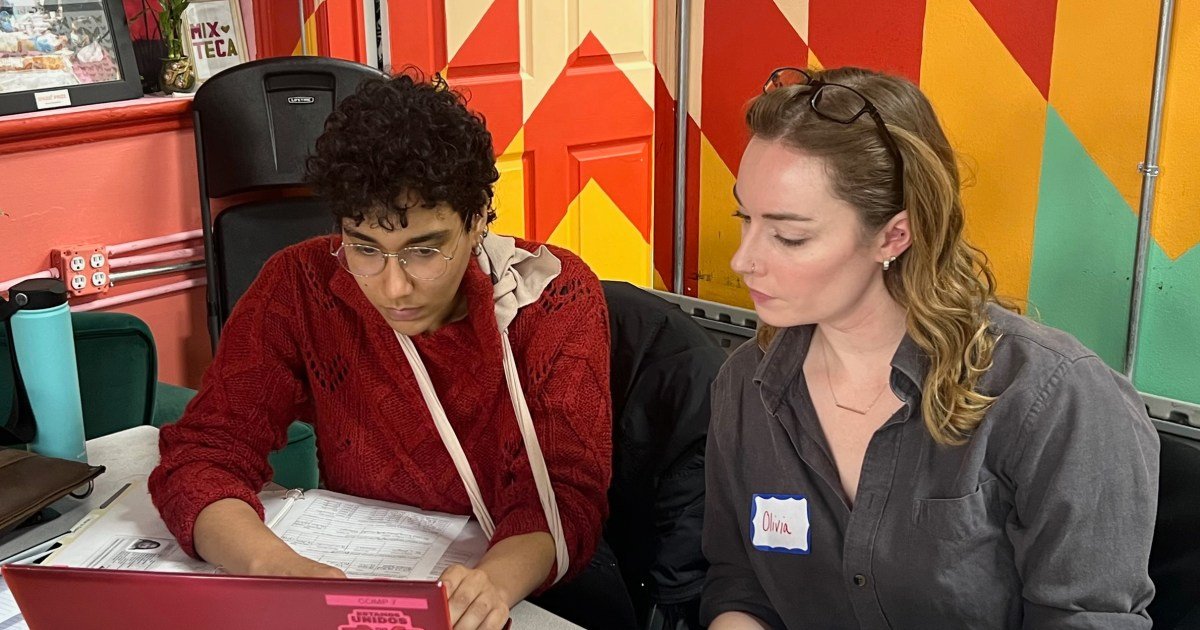

On a Monday afternoon in January, the South Brooklyn Shrine is packed with dozens of volunteers, translators and migrants. Migrants raise a series of pressing questions: What will the incoming Trump administration mean for their pending asylum cases? How do you fight a deportation order? And, in the worst case scenario, how to prepare for family separation?

They fear that as soon as President-elect Donald Trump is inaugurated on Monday, he will make good on his campaign promise by ordering widespread deportations across the country. The 210,000 undocumented people who have arrived in New York City since 2022 also face Mayor Eric Adams’ closure of the Floyd Bennett Field shelter, which houses 1,800 people, and his threats to roll back the city’s sanctuary policies by overturning the opposition of the City Council with an executive order. Incoming Trump and Adams administration officials met to discuss deporting immigrants who have committed crimes.

Emily Schectman, director of the South Brooklyn Sanctuary, said the organization is doing everything it can to prepare for the uncertainty ahead. In recent weeks, 150 new volunteers have signed up and more are expected after the opening. “We anticipate that we will do a lot more deportation defense, ICE surveillance and family separation work,” he said.

South Brooklyn Sanctuary is one of dozens of groups nationwide that operates as a pro se community, teaching immigrants to represent themselves “on their own behalf” in the legal system with voluntary support. The nonprofit has worked with more than 5,000 immigrants since opening in 2022 with a group of more than 100 trained and active volunteers. Last year alone, they helped 715 immigrants file change of address forms so they wouldn’t miss their court dates and risk being deported.

Once in office, Trump has promised to launch the “largest deportation program in American history,” send Congress a bill to ban sanctuary cities, and request funding to hire and retain 10,000 new border agents. He has also said he will restrict federally funded benefits only to U.S. citizens and reinstate and expand a travel ban targeting Muslim-majority countries. During a December interview with NBC’s “Meet the Press,” Trump claimed he had “no choice” but to deport millions of people and that “they are costing us a fortune,” a claim that has been questioned by economists.

To prepare for future work, South Brooklyn Sanctuary is raising funds for a full-time attorney and creating a new program to help immigrants file motions to reopen their asylum cases, which can combat deportation orders. It is also expanding into a new space this month, where it will train a new group of French- and Arabic-speaking volunteers to accommodate the growing number of immigrants from African countries.

“Our promise to the community is that we will remain informed and prepared for any policy changes that occur,” he said.

Train volunteers to support migrants

Emelis, who asked that her last name not be used for fear of being deported, said she left Venezuela after being attacked by the military for her high school protests against authoritarian President Nicolás Maduro.

The 26-year-old almost ran out of time to apply for asylum when she attended Brooklyn South Sanctuary’s walk-in immigration program at Good Shepherd Church in Bay Ridge; Asylum applications must be filed within one year of the applicant’s date of arrival in the United States. With the help of volunteers, he filled out his asylum and work permit forms just in time.

“I felt scared when I first arrived, but I received my work permit just a month later,” Emelis said.

The South Brooklyn Sanctuary was founded in the wake of Texas Governor Greg Abbott’s decision to bus more than 27,300 immigrants to New York, citing the need for border security. More than 8 million migrants have crossed the US-Mexico border since 2020 due to political repression, gang violence, poverty and natural disasters, and many of them have settled in immigration centers in large cities. cities struggling to rapidly expand their safety net. As of 2024, the number of border crossings and new immigrant arrivals to New York City and other major metropolitan centers have decreased.

In Brooklyn, Juan Carlos Ruiz, pastor of the Church of the Good Shepherd, and residents welcomed their new neighbors to a weekly drop-in program with information about immigration, hot food and clothing. They soon realized that what immigrants also needed was knowledge about their rights.

At the time, New York City legal clinics were overwhelmed by the influx of immigrants struggling to find free legal representation. Other cities saw the same thing. The Migrant Solidarity Mutual Aid Network in Washington, D.C., and Mountain Dreamers in Frisco, Colorado, were just two of many organizations formed in the absence of local government and nonprofit services to help migrants complete immigration applications. asylum and employment authorization.

In New York, the city’s official asylum center imposes strict restrictions on who can make an appointment to apply for asylum: Immigrants must be in the city’s shelter system, be eligible for work authorization and not have been in the country for more than 11 months. Meanwhile, many immigrants who arrive at immigration court are unprepared and often appear without legal representation. Nearly 44% of immigrants in New York state are fighting their cases alone, Schectman said, and many do not speak English, know their rights or have any legal training.

“In the absence of attorney capacity, we want a strong pro se community that can fill that void of justice,” Schectman said.

Preparing for upcoming policy changes

Maria Meneses, 45, also received asylum and began volunteering at the South Brooklyn Sanctuary last summer to share advice that had once benefited her.

He sits down with asylum seekers and tells them he understands the traumas they carry with them. Meneses asks for any evidence of violence or abuse to strengthen his case. “I tell them it may be embarrassing, but it’s important to show what happened to you,” he said.

Meneses emphasized the importance of asylum seekers naming the specific gang that threatens them and the cities in which it operates. “Due to high levels of corruption, many of these gangs are serious economic and political operations embedded in the government,” he said. “It can be argued that resisting them leads to government persecution.”

Meneses said that while her personal experience makes her an effective volunteer, it can also take its toll. “These families put all their dreams into the asylum process,” he said. “They are forced to tell the most terrible things that have happened to them and the reason why they left everything behind.”

But seeing that South Brooklyn Sanctuary’s group of volunteers has more than doubled over the past three months gives him hope. “It’s inspiring to see how the people of New York City show up to support their community,” he said.

For now, Emelis is building her life in New York. After being granted a work permit in 2023, she found work as a home help at a temp agency. He can spend time with his son and his siblings after his night shifts. “All I want is to give my son a better future here,” he said.