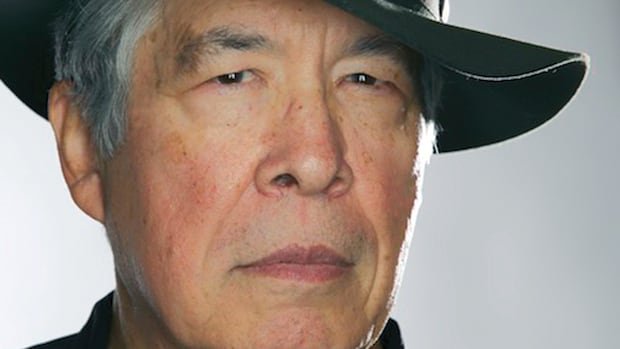

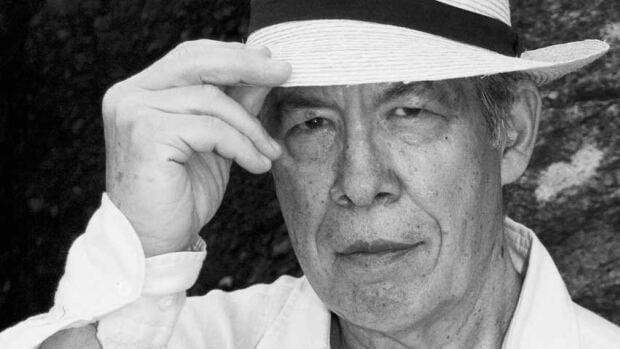

How it happens6:35Thomas King revelation is ‘a stain on the entire Canadian literary industry,’ says Niigaan Sinclair

For Anishinaabe writer and scholar Niigaan Sinclair, the revelation that Author Thomas King is not indigenous. It’s painful.

King is an award-winning Canadian-American author who He made a living writing about his complex relationship with indigenous identity, most notably in his 2012 book. The uncomfortable Indian.

But on Monday he revealed in a globe and mail editorial that he “is not Indian at all.”

King wrote that he had always believed his mother’s story that he was part Cherokee on his estranged father’s side.

But recently, he wrote, the Tribal Alliance Against Fraud (an organization that exposes false claims about Native American heritage) informed him that there is no Cherokee ancestry in his family tree and showed him the genealogical research to prove it.

““I’m still reeling,” King, 82, wrote.

Sinclair is also reeling. In a column for the Winnipeg Free Presscalled the news “a punch in the gut, a pipe bomb, and an act of pulling the rug out from under the publishing world, even if King did nothing out of malice.”

Sinclair, a professor of indigenous studies at the University of Manitoba, spoke with How it happens host Nil Köksal. Here is part of their conversation.

Thomas King writes that he is still in shock about all of this. How is it affecting you?

There isn’t a single person who has worked in Indigenous studies or Indigenous literature or, frankly, anything related to Canadian literature, who hasn’t heard of Tom King.

It’s not only painful. I think it’s also a stain on the entire Canadian literary industry as a whole to not check and not ask questions and let a person… take take up so much space.

He also wrote…that he believed what he was told, that his father’s biological father was part Cherokee. How can you balance the complicated history that many people have while also advocating for accountability and clarity for people who are doing work like Thomas King has been doing?

We all have complicated identities, you know? Each indigenous person has different cultures, races, stories of displacement, loss of identity, residential schools.

But what we have to do is we often have to [legitimize] ourselves in different contexts and localities, especially when it comes to the work we do in our own communities.

You have to reconnect. You have to be able to answer the necessary questions. And people will trust you because you said you did the work.

But the fact is, he didn’t do the job. He let others do the work for him.

If you don’t even ask for help so you can reconnect and find the answers to the most critical stories, then what happens is you create a mess that everyone else has to clean up. And that’s really what is created now.

We all have this situation on our hands where not only do we have to review elements of our career and rewrite and rethink a lot of the things we’ve been working on, because we built them on a foundation of trust, but now we also find ourselves in a situation of distrust and harm that has been created as a result of this process.

How do you process this personally and then advise others to work through it?

The harm is real for all indigenous people. We know how to cope, we know how to support each other and, most importantly, how to recover and rebuild. Without a doubt, we all know how to deal with a situation like this.

This really speaks to an issue of the Canadian literary landscape and Canadian culture as a whole. Why have so many of these people who have very dubious and problematic rights over indigenous communities taken up so much space for such a long period of time? And I’m not just thinking about Thomas King.

I think that’s really the big question.

You write in your article that you met Thomas King through your father, the late Murray Sinclair. And there were rumors spinning [about King’s ancestry]. And Thomas King writes about this too, that he knew rumors were circulating and that they would go away. What did you talk about? What did you tell your father?

I’ve probably heard these rumors for over a decade, maybe even longer. And I remember going to my dad and talking about it.

My father, because of his long relationship with Thomas King, trusted him. And my father said, you know: I take him at his word.

And then I believed my father. And I’m actually very happy that he’s not seeing a day like this, because I know he would be sorely disappointed.

I don’t think he would in any way want any of us to cause more harm. But I think… I would like us all to turn to those authors that we may have overlooked in the past, who didn’t win those awards, who didn’t take up as much space. [King did]and revisit those authors and pay them a little attention.

Of course, we have covered in the past, the news about [musician] Buffy Sainte-Marie is exposedother high-profile Canadians, Joseph Boyden too. How or where does this case fit…? Do you feel different?

This one is a little bit different because in this case, I have a lot of empathy because if someone has been told a family story, someone in their past has told them that they come from a particular community, they might want to believe it. They have such a desire to believe that they do not do the necessary research, even when others clearly can do the research and find the answers. And that if they don’t pursue it, I can feel some empathy for that.

But where empathy ends is when you take up so much space, win all these awards, and then displace real-life Indigenous writers for that long period of time.

If someone wants to talk about Indigenous identity for 25 books and impact not just ourselves, but an entire country, then what does that say about the country itself and the country we live in?

I think many of us want to be very optimistic and believe that reconciliation is moving forward and changing and making us more progressive than ever. But this really brings to mind a time in this country when non-indigenous people are dictating the lives, parameters, and arts of indigenous people. And we have to leave that behind.