HILDALE, Utah — Few people talk about vaccines here. At least, not to outsiders.

In general, people who live in Hildale, as well as in neighboring Colorado City, just across the state line in Arizona, are tremendously private. High walls surround many of the houses to prevent the prying eyes of strangers.

The measles came in anyway.

As of Friday, 161 cases had been confirmed in Utah and Arizona, most concentrated just along the border in the twin cities known collectively as Short Creek. Eleven people (eight in Utah and three in Arizona) were hospitalized.

It has now become the site of the second-largest measles outbreak in the United States this year, behind the outbreak that spread from west Texas to New Mexico, which sickened at least 862 people and killed three. Two were girls.

Vaccination rates have fallen precipitously in both outbreak areas in recent years, and from the outside, the two have similarities. Both outbreaks took hold in communities deeply skeptical of government intervention and conventional medicine. And both outbreaks largely affected people with strong ties to religious sects: Mennonites in West Texas and (mostly former) members of the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (FLDS) in Short Creek.

But the Short Creek community is also grappling with its recent past: a past of polygamy, expulsion of children and a cult-like leader now imprisoned for sexual assault of minors.

“We had a lot of trauma,” said Donia Jessop, mayor of Hildale and former FLDS member. “Vaccinating children or giving them a booster dose was not the first thing on our mind.”

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints banned polygamy more than 100 years ago. Some members, however, continued to believe that multiple wives benefited men in the afterlife and broke away, becoming the FLDS. One of the places where members settled was Short Creek.

Jessop fondly remembers growing up in the 1970s and 1980s in a close-knit community with two mothers and dozens of brothers, sisters and cousins who were her best friends.

“I had an ideal childhood,” he said. “Any mother in the city guaranteed me a beating or a meal, because we were raised like in a village.”

But polygamy was and is illegal. The practice prompted two federal government raids in Short Creek, one in 1953 and another in 2008. On both occasions, government officials temporarily separated children from their families by force in an attempt to determine whether the children were being abused or neglected.

The children were returned, but the trauma remained. “That made a lot of us FLDS kids very afraid of police officers,” said Gloria Steed, who was 14 during the 2008 raid. “Afterwards, we were very hesitant about being told what to do.”

Steed said his mother was born around the time of the 1953 raid and grew up with anti-government and, in turn, anti-vaccine tendencies. “It really affected their faith and trust in the systems,” said Steed, who was not vaccinated as a child.

Still, there was never a specific religious mandate against shooting, Jessop said. She was vaccinated when she was a child. (No major religion expressly opposes vaccines.)

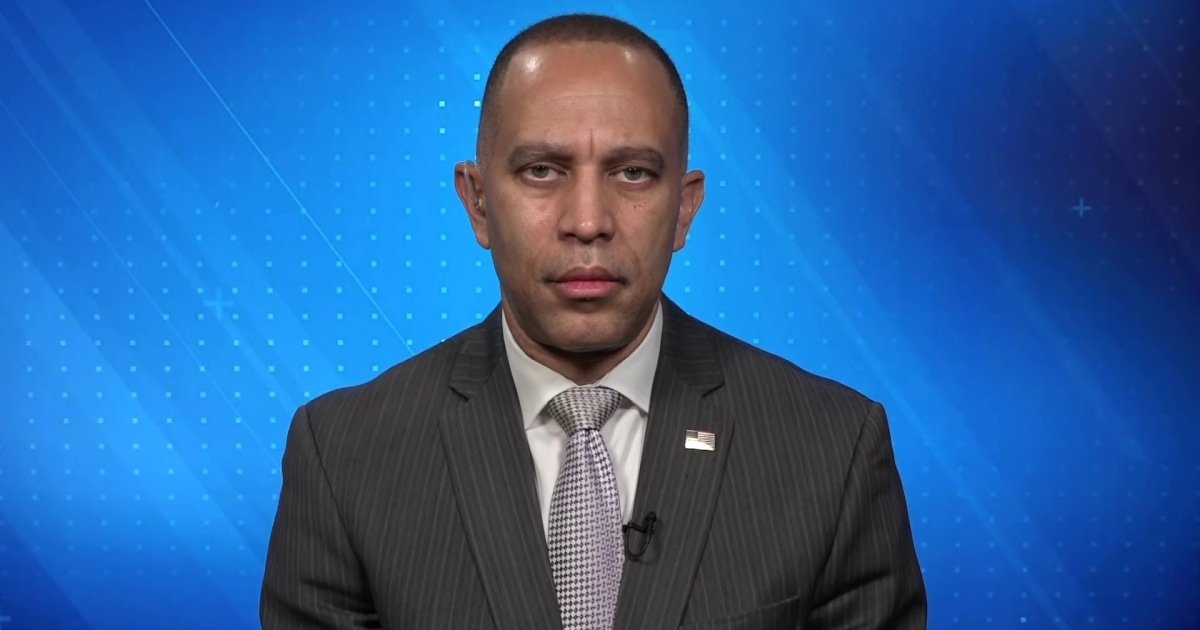

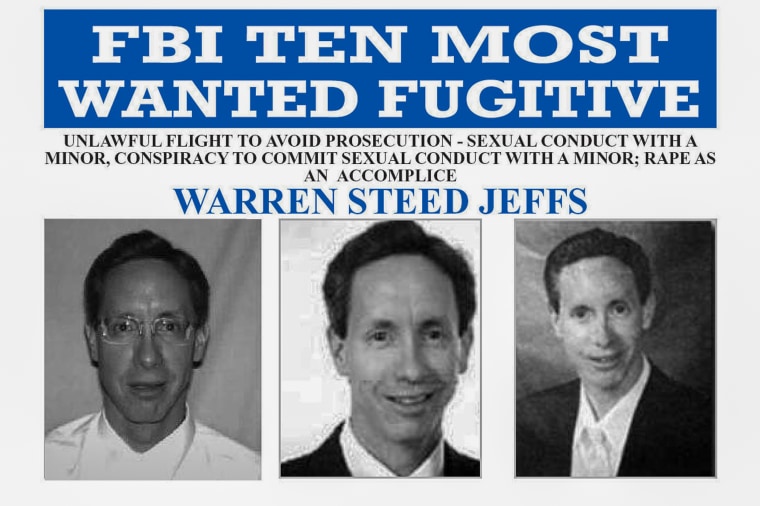

Things changed, Jessop and other former FLDS members said, in 2002. That was the year Warren Jeffs, the now-imprisoned cult leader, became their prophet. An FLDS prophet is considered to be the direct voice of God. He often has dozens of wives.

Briell Decker, Jeffs’ 65th wife, said he spread lies about vaccines.

He “said vaccines are bad and contain substances that prevent you from having children,” said Decker, who has since abandoned the FLDS lifestyle. The ability to procreate and have many, many babies is critical to keeping the community going, Decker and other former members said.

Jeffs exerted more control over the Short Creek community than previous prophets, former FLDS members said. He seized their lands and homes, they said, even reassigned wives and children to different husbands and fathers, splitting families and stripping them of the ability to contact each other.

Jessop, who was not mayor when Jeffs was prophet, also said Jeffs restricted access to the city’s medical clinics to people he deemed unworthy before shutting down the health care system entirely.

Jeffs was on the FBI’s Most Wanted list before he was arrested in 2006. He is serving a life sentence for sexual assault of minors within the FLDS community.

The wounds of the Jeff era in Short Creek run deep. The area has had to work to restore the basics: running water, schools and a health care system, including routine medical checkups.

With so much to rebuild, making sure children were up to date on immunizations was on the priority list, Jessop said.

While there are two medical clinics in Short Creek, businesses promoting natural and herbal remedies have become a popular substitute for medical care.

At Paty’s Place, a popular health food store in the area, a store employee said some people had come in looking for advice on treating measles. The store’s owner, Paty LeBaron, did not respond to NBC News’ requests for comment, but wrote on Facebook that she has never “made claims about knowing how to cure measles” and encouraged people “to seek reliable, science-based medical advice from qualified health professionals about measles or any other serious health condition.”

A similar phenomenon was observed in West Texas: In the town of Seminole, parents of children sick with measles flocked to Health 2 U in search of cod liver oil, an unproven remedy touted by Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr.

The Covid pandemic made efforts to restore routine health care even more difficult, said Aaron Hunt, a public health expert with the Utah State University Extension Program.

“Parents are trying to do what they think is best for their children,” Hunt said, “but since Covid, they’ve been exposed to a lot of misinformation.”

That makes moms and dads fear even the rare side effects of vaccines, said Hunt, who works with health care providers across Utah to help them combat misinformation about vaccines. (The drop in vaccinations hasn’t just opened the door to measles; whooping cough is also spreading across the state.)

“You have to have honest conversations with people and give them the power to make their own decisions for themselves and their families,” Hunt said.

But now that measles is spreading through the Short Creek community, people seem to be embracing the vaccines. Jessop, the mayor of Hildale, said there has been a “sharp increase” in vaccinations since the outbreak began.

David Heaton, spokesman for the Southwestern Utah Department of Public Health, said the area saw a 14% increase in vaccinations between July and September of this year, compared to the same period in 2024.

However, a spokesperson for the Arizona Department of Health Services said current MMR vaccination rates are on par with those in 2024.

The spread of the virus is not limited to the Short Creek area. In recent weeks, measles exposures have also been reported in the Utah cities of St. George and Hurricane. On Wednesday, Salt Lake County public health officials said there was a probable case, but they could not confirm it because the person in question refused to be tested.

Becky Goimarac lives in St. George, about 45 miles from Hildale. His teenage son was exposed to the virus at a high school cycling event in Park City, Utah, in August. That was the first indication of a measles outbreak in the state.

“Personally I wasn’t worried because my children are vaccinated,” Goimarac said. “It made me more sad that we had to worry about that kind of thing.”

Steed, the former FLDS member who is now 31, remembers being sick with whooping cough and chickenpox as a child. But he still has reservations about vaccines aimed at preventing those diseases.

“I don’t trust the system,” Steed said. “I feel like doctors are pushing too many vaccines too soon.” The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, along with the American Academy of Pediatrics, maintain that the childhood vaccine schedule is carefully researched to offer the strongest protection with the fewest number of shots.

Still, Steed allowed her 9-year-old son Jhonde to receive some of the vaccines she considered most important so that he would not have to suffer like she did. “I thought whatever I got as a kid, I would be doing my son a favor if I got it,” she said. In addition to the chickenpox and whooping cough vaccines, Jhonde received a dose of the measles, mumps and rubella vaccine as a baby. Two doses are recommended for 97% protection.

When the measles outbreak began in Short Creek in late summer, Steed received the MMR vaccine because she was on her way to becoming a surrogate mother. Measles during pregnancy is a major risk factor for miscarriage or premature birth. Jhonde received his second dose of MMR the same day, Steed said, based on his trust in local doctors and nurses who also grew up in Short Creek.

Steed sees firsthand the benefit of MMR vaccines as the outbreak has increased in her community.

“The vaccines are working. It’s been a blessing to see,” he said.

“It’s really about having doctors and nurses willing to listen to patients’ individual experiences, rather than always trying to pressure them to do something because they think they’re better or smarter,” Steed said. “The medical field can be a bit of a cult, you know?”