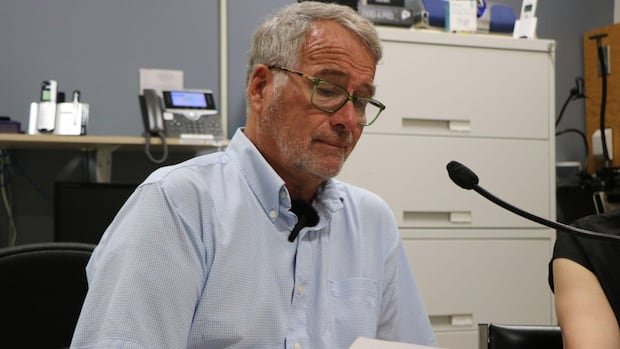

Leaning in a small microphone in a study by the city of Quebec, Dr. Alec Cooper breathes and reads part of the often quoted “to be, or not to be” Shakespeare’s soliloquy Village.

“It’s quite dramatic,” Cooper said, moving away from the microphone and leaving out a laugh.

“I just realized, my God is really talking about death.”

He is a subject that Cooper says he has been forced to think during the last year and a half after Als diagnosed him, a disease of terminal motor neurons. Initially he was given an average life expectancy of two to five years.

The family doctor, originally from Victoria, had 1,800 patients before announcing their fast retirement last year.

Staying busy renewing your home to become accessible to wheelchairs, Cooper has also spent more time in front of a microphone: registering such common, elaborate poems and their favorite book passages as part of the process to clone its voice for when the disease progresses even more.

Elevenlabs uses voice technology, a company based in the United States that offers technology to one million people suffering from degenerative diseases, including ELA, Boca cancer, victims of stroke or those with Parkinson’s disease.

The ai tool allows users to enter a small amount of audio that generates a voice clone with the natural tone and inflection of that person when they need to trust text devices. Cooper began feeding Elevenlabs Bank at home and is receiving help from professionals at the local rehabilitation center.

“When the voice is gone, it has gone forever,” Cooper said.

“Thanks to this technology, the disease cannot remove my voice.”

‘Face him with tremendous courage’

Compared to most people who have a diagnosis of ELA, Cooper says he has considered a “slow progress” and that he looks “pretty good.”

Even so, the symptoms of the disease are dragging. He says he is beginning to have trouble dressing, making buttons and driving utensils.

His friend, Dr. Jean-Pierre Canuel, whom he was diagnosed with ALS 11 years ago, is more advanced.

Canuel, a retired doctor, still gardens using her grass cutter, conducts an adapted truck and is dedicated to her hobby of making wooden charceria boards.

Sitting in his motorized wheelchair, he smiles while sliding the photos of his grandchildren. A great effort to speak is needed, but Canuel tells CBC that before his diagnosis, “I was a strong man.”

He did not have the opportunity to register his voice before his speech was severely affected by the disease. Canuel exploded in tears when Cooper greeted him in the recording area in the city of Quebec in a wet morning at the end of June.

“The voice has been removed, what happens to us all,” Cooper said, resting his hand on Canuel’s back, comforting him.

“It faces it with tremendous courage.”

It is an approach that Cooper is trying to adopt, he says, taking all the advice and inspiration of Canuel as possible.

“I will have all the misty eyes again, but Jean-Pierre is an incredibly brave person. This is how I want to be,” he said, decomposing.

“You have to hug him and not deny it.”

Improvement of the quality of life

The cloning of the voice of AI is relatively new, says Dr. Angela Genge, head of the Center for Excellence Als at the Neurological Institute of Montreal. She says that until the last decade, it was not widely available for patients.

But multidisciplinary clinics can now offer patients relatively early voice bank in their diagnosis, she says.

“It makes a big difference for them,” said Genge, a professor at McGill University. “I see the AI helping with the quality of life and I think it is quite significant.”

She says she is used to listening to computer -generated voices that articulate what patients mean. Before the “computer era”, he says that patients were limited to talking with punctuation cards.

Now, when the disease progresses to the point of impacting speech, a patient can be equipped with devices that can formulate words and sentences in their own voice, says Sophie Dupont, a pathologist of speech language for the local health authority that works in the Réadaptation Institut in deficience Physique de Québec.

“When we talk about text, you will literally be writing first [on a tablet] If you can still, “he said.

The tool can also be adjusted to use through the control or monitoring of the head, as well as the voice generation device used by the renowned physical Stephen Hawking, which Als had, says Dupont.

Usually, when patients reach their office, their ability to speak is already affected, she says. In these cases, she trusts recordings or voice emails to boost a voice of AI.

After working with Cooper during the last six months, Dupont says that tool AI is used exceptionally. She says she has to balance the urgency of the needs of patients with current resources.

‘It’s going to be a legacy’

Traditionally, the robotic voices available for patients with ELA did not come in all shapes and sizes, says Dustin Blank, based in Los Angeles, who leads the associations in Elevenlabs.

“Now every dialect, every language … sounds like you,” he said.

“It’s how they talked in that same cadence, in that same emotion. And that is very powerful.”

He says that the company’s impact program expects to find ways to put their voice technology in the hands of the people who need it most.

With the concerns about the power and security of AI, he says that the company understands that the voices and the process of cloning them are “powerful things.”

Taking measures to protect the voices of people with password protection and voice verification, the company takes security “very seriously,” he says.

Sylvie Barma, 30 -year -old Cooper’s wife says that this tool is proof that AI is “not just bad things.”

While her husband enjoys the process of using the AI tool, for barma, the recording process is a reminder of the reality of the disease and the challenges that the couple faces as Cooper’s health deteriorates.

When he listens by recording at home, Barma says he goes out to his sanctuary: his garden.

“I move away,” she says. “We know what is coming, but I prefer not to think too much.

“It’s going to be a legacy.”