Unreserved50:51Inuit drum dance strength

Sophie Agnatok and Ashley Dicker are known for decades. Today they are closer than ever, in more than one sense.

“We are on the other’s face,” said Agnatok, referring to how, as partners of the scent of throat, they perform close to each other.

“It’s really intimate and requires a lot of approach and so much connection.”

Agnatok’s first memories of Agnatok date back to his childhood in Nunatsiavut, a region governed by Inuites in northern Labrador.

“When I was a girl, I entered Sophie’s room with my best friend, who was her sister, and I stole her perfume,” Dicker said, laughing.

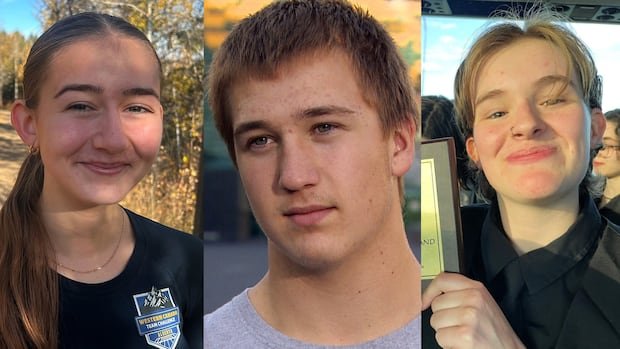

Agnatok and Dicker are members of Kilautiup Songuninga, which translates as “drum strength.” They are the first Inuit dance and throat song group that leaves St. John’s. Agnatok is now the president of the group. As a founding member, he has been part of the group for nineteen years. Dicker joined four years ago.

“Before I had Ashley, I had been dying and dying for a fellow of the throat. Finally I got one,” said Agnatok. “I am very lucky to have it.”

During the last two decades, Kilautiup Songuninga has been gathering songs and stories to revive the ancient tradition of Drum Dance Inuit. Although the songs were often interpreted by men, it is the women who lead the resurgence.

For the six members of Kilautiup Songuninga, the community is part of its raffle.

“It’s hard for Inuit to meet here,” Dicker said. He moved to St. John eight years ago and joining the group helped her fight nostalgia. “It’s so good to be somewhere [you can be yourself]or with people with whom you could be yourself. “

Claiming culture

Kilautiup Songuninga also helps its members recover aspects of their culture to which many of them grew without access.

“When we started, we did not know our traditions, it was not mentioned. They did not show us our songs, they taught us music from the Church,” said Agnatok.

The song of the throat and the dance of drums were feared and prohibited by Moravos missionaries who saw him as worship of the devil. Instead of traditional Inuit music, they forced the adoption of brass instruments and choral song.

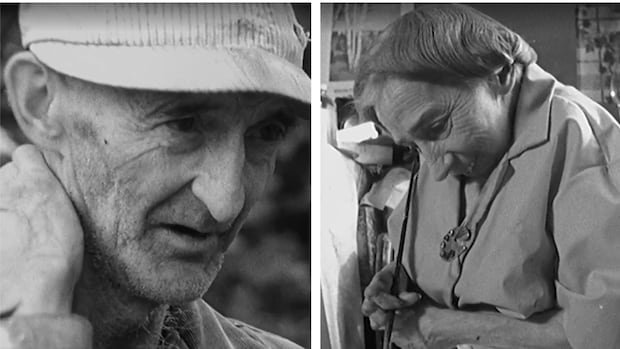

Agnatok was raised by her grandmother, herself a throat singer. That legacy inspired Agnatok, although his grandmother did not show him the practice.

“I was cleaning one day and I found this newspaper cut, and it was my grandmother. She was here [in Newfoundland] For the popular festival in 1984. And I’m like, Wow, “said Agnatok.

Dicker’s trip to traditional music was lit by a similar passion for revitalizing his culture. She never saw her grandparents or other elders in her community by practicing her musical traditions.

“I wanted our elders to see us … I wanted them to be proud and fight to recover it, and be proud of ourselves, but especially for the people who were not allowed to be proud of themselves.”

Learning process

Growing up, Agnatok saw Drum Nain dancers claiming the battery dancing in his hometown. She points out that Nunatsiavut becomes self -governor in 2005 as an inciting time for greater reconnection to Inuit culture, even through Kilautiup Songuninga.

The learning techniques and the songs that were almost lost come with their part of challenges for the group. They trust a variety of sources, including CD, Internet and Inuit knowledge guardians to build their repertoire.

“It can be a bit difficult, trying to lower the technique and reduce the right music,” said Agnatok.

Language, in particular, can be an obstacle.

“Many of our members … We are not complete Inuit speakers like many of our ancestors, or even some of our elders now,” said Agnatok. “But we want to make sure to sing correctly when we sing in Inuktitut, our mother tongue.”

‘Inuk to the nucleus’

For almost two decades, Linuep de Kilautiup Songuninga has changed. Last December, Founding Member Solomon Semigak died.

“It was special,” said Danny Pottle, who was invited to join the group in 2004. “He taught us patiently, with skill, and was a good guy.

Agnatok remembers Semigak as a strong speaker of Inuktitut, a diplomatic group president and his right on the right.

“We are touching. We still talk about him,” said Agnatok. “I know I would be very proud of all of us, believe me. And with his niece joining the battery group, that is also a great thing.”

The new Sophie Semigak member joined the group earlier this year, in memory of his uncle.

“He was like a father for me,” he said. “He also accompanied me around the hall, when I got married. So he is very, very special to me.”

Agnatok says that Semigak would be proud to see his niece staggering.

“We can go to the back as a family, but we are all familiar. We all also support each other, in our way. And that’s what it is about,” he said.