Warning: This story discusses school violence, sexual assault and suicide.

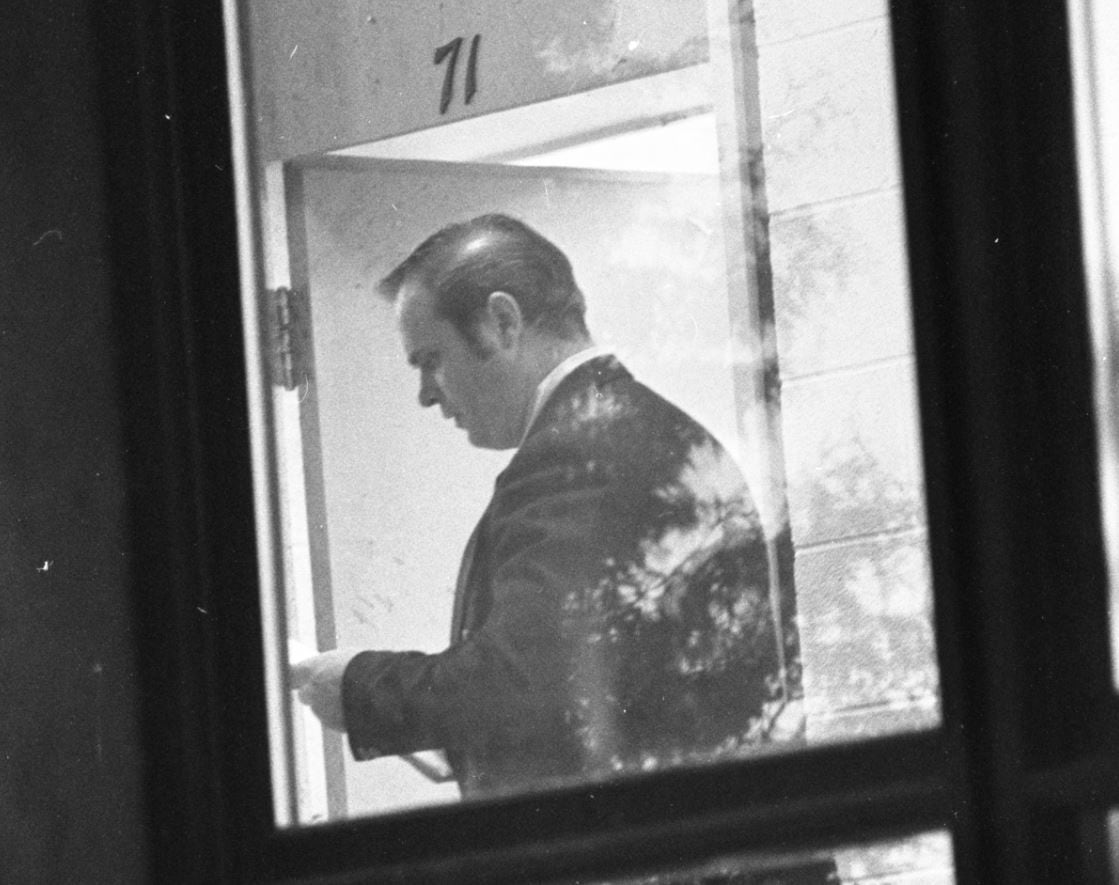

Ten years ago, Dennis Curley went back to what he calls “the scene of the crime” — back inside Classroom 71 of his Ottawa school.

The St. Pius X High School alumnus was on a personal mission, bent on getting his life back.

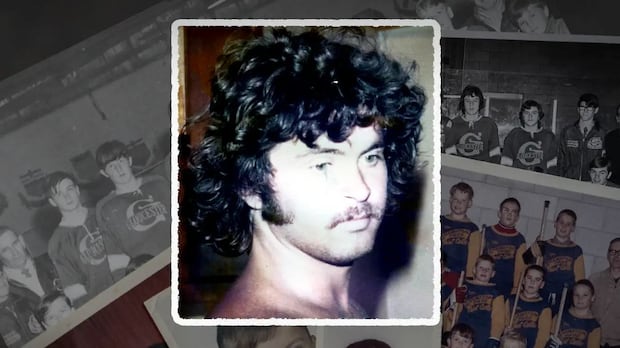

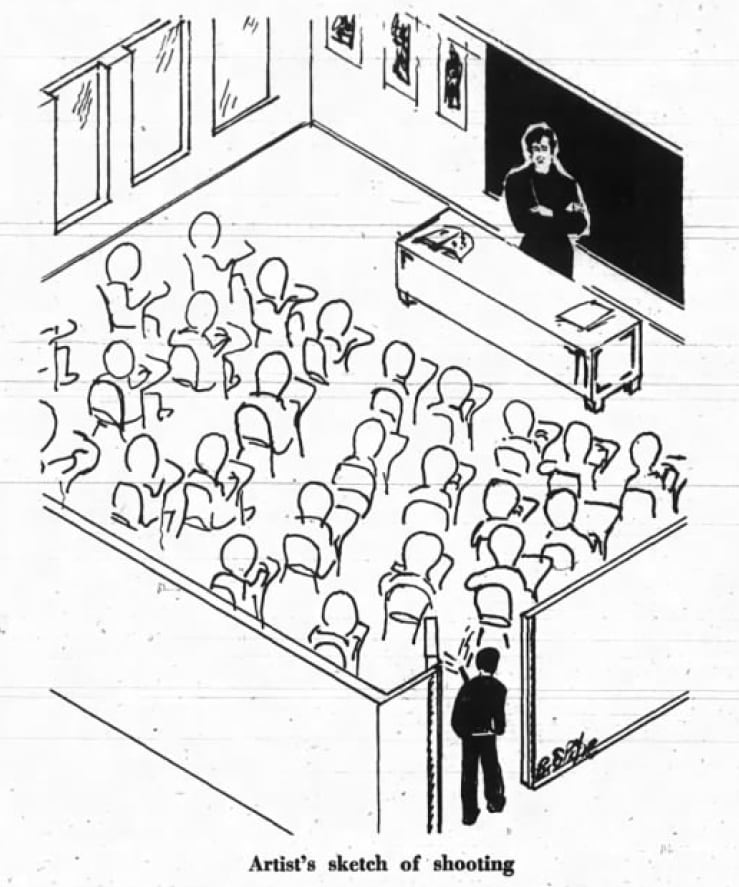

For decades, Curley was gripped by nightmares about Oct. 27, 1975, the day a severely troubled classmate named Robert Poulin opened fire on their packed religion class with a shotgun bought at Giant Tiger.

It was one of Canada’s first school shootings, and helped pave the way for new federal gun control measures. But it was only one half of what made that day so awful.

That morning, Poulin raped and murdered a neighbour and aspiring doctor, 17-year-old Kim Rabot, who was a student at Glebe Collegiate Institute. He then biked to St. Pius, wounded several more students, and killed himself in the hallway with the gun.

Mark Hough, an 18-year-old with plans to attend law school, was among those injured. While everyone else in Classroom 71 recovered — physically, at least — Hough died in hospital over a month later.

Curley, now in his 60s and a psychotherapist, is thankful “there is no white line around my body,” as his professional profile page states.

But Curley struggled for years to understand how “a good man” like Hough could be killed while “a jerk like me” kept on living.

He finally sat down with his own psychotherapist and hit upon the idea of going back to the classroom.

So that’s what Curley said he did on Oct. 27, 2015, with the school principal guiding him by the arm.

When it came time to leave Classroom 71, however, Curley froze, seized by the memory of opening the door in 1975 and seeing Poulin’s body.

He then fell to his knees and began to cry.

‘Stories are lost if they’re not told’

Curley did manage his way out of the classroom, and in the 10 years since, he says he hasn’t had a bad dream about the shooting.

“When we face our fear, we’re set free. We bury the fear? We’re in bondage,” he says.

All that being said, Curley doesn’t necessarily recommend everyone follow in his footsteps.

“You have to decide that for yourself,” he says.

The October 1975 shooting at St. Pius, along with the equally shocking murder of Kim Rabot, was a transformative event for Ottawa in its time.

But in the last half-century, the city’s collective memory of that moment has faded — while those deeply affected have each wrestled and coped with the aftermath in their own ways.

In this concluding chapter of a four-part series examining the murders’ painful legacy — which began by looking at the events in full before focusing on the tragically short lives of Rabot and Hough — CBC is now turning to the St. Pius survivors to hear about the shooting, its impact, and the days and decades that followed.

Several declined to be interviewed, saying it would be too difficult.

“Every time I think back to that day, I plummet into a depth of sorrow and I do not want to experience this feeling,” wrote Lori Mladek, a Classroom 71 student at St. Pius who also knew Rabot, in a text.

Others don’t want the events of that day to define their lives.

But to mark Monday’s 50th anniversary, Curley, fellow survivors, other St. Pius graduates who were at the school that day, and former teachers are offering their personal remembrances, including previously unheard stories of heroism and healing.

Newly unearthed personal, Ottawa Journal and CBC archival materials offer additional insights into one of the darkest chapters in the city’s history.

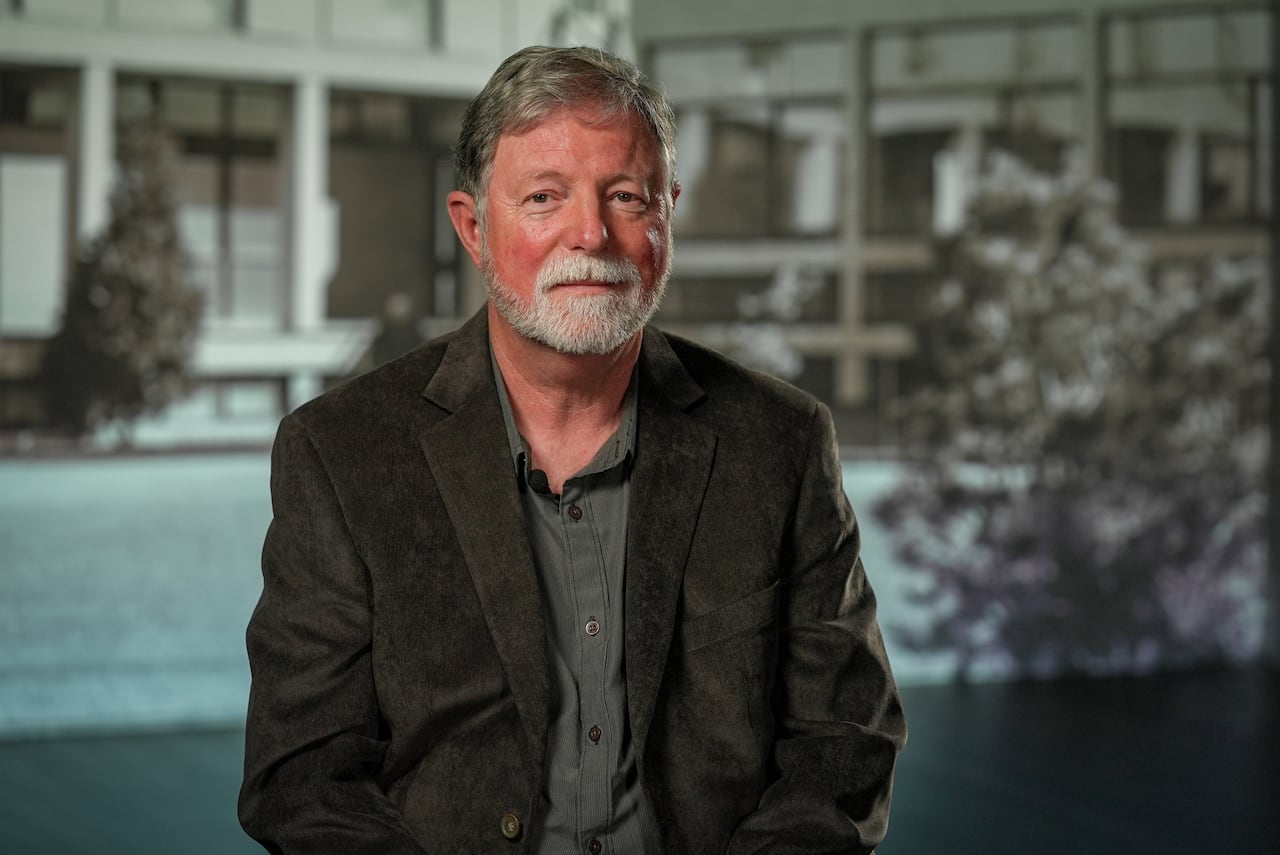

“Memory is a very fleeting thing,” says Bob Davidson, who was in the room next to Classroom 71 and went on to become a career paramedic in Ottawa.

“Those stories are lost if they’re not told in some way.”

Dave Albert was one of the teachers at St. Pius X High School when a student opened fire on his classmates and took his own life with the gun on Oct. 27, 1975. Albert died four years ago, but his account of the shooting’s aftermath survives in taped conversations with one of his former pupils, Shawn Charland. Charland shared the tapes with CBC. (Videography and editing by Mathieu Deroy. Production design by Michel Aspirot. Additional videography by Francis Deschênes.)

Part four: Beyond Classroom 71

Some of the students who were at St. Pius on Oct. 27, 1975, say that despite what happened, the school still occupies a special place in their hearts.

At the time, Ontario teens in upper grades had to pay tuition, so if they were at St. Pius, there was a good chance it was because they wanted to be there.

Liam Maguire, who took the bus to school with Hough and was in the cafeteria when the shooting unfolded, adds that being at St. Pius on the day of the shooting imbued him with some “extra resolve.”

“I came through the most tumultuous day and time in that school’s history,” he says.

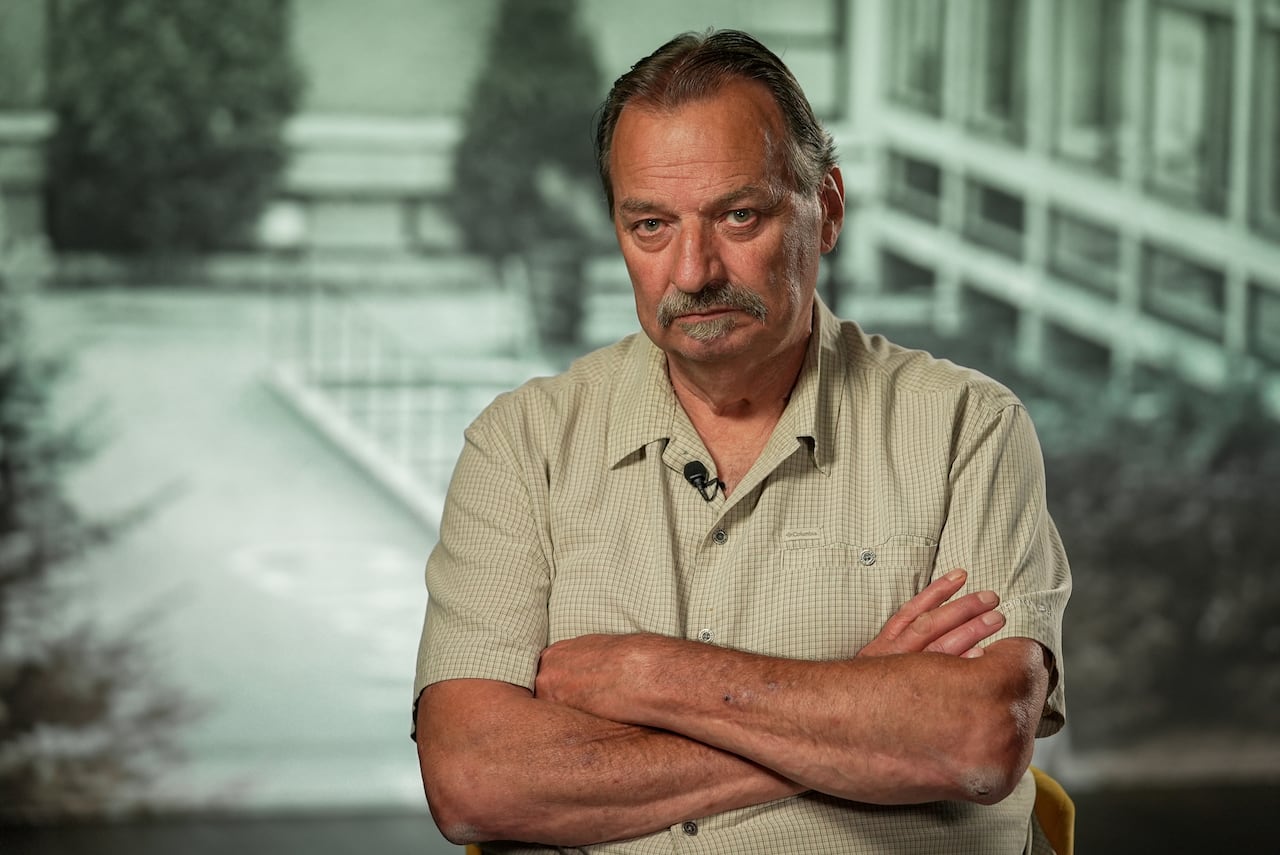

For shooting survivor Terry Vanden Hanenberg — now a retired 68-year-old civil construction contractor with grandkids — St. Pius was literally home. He boarded and attended school there for several years.

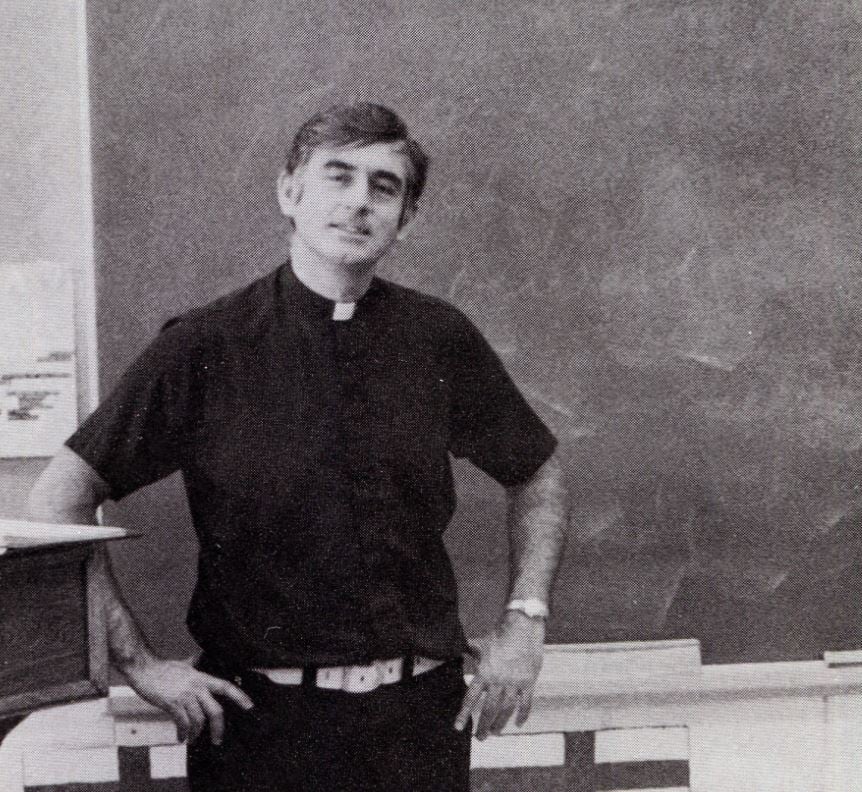

After Poulin wounded Vanden Hanenberg, Father Len Lunney, the principal of the school, administered last rites because he was unsure if he’d survive.

“There might have been one bad [memory], but there were a lot of good memories here [too],” Vanden Hanenberg said outside the school earlier this year.

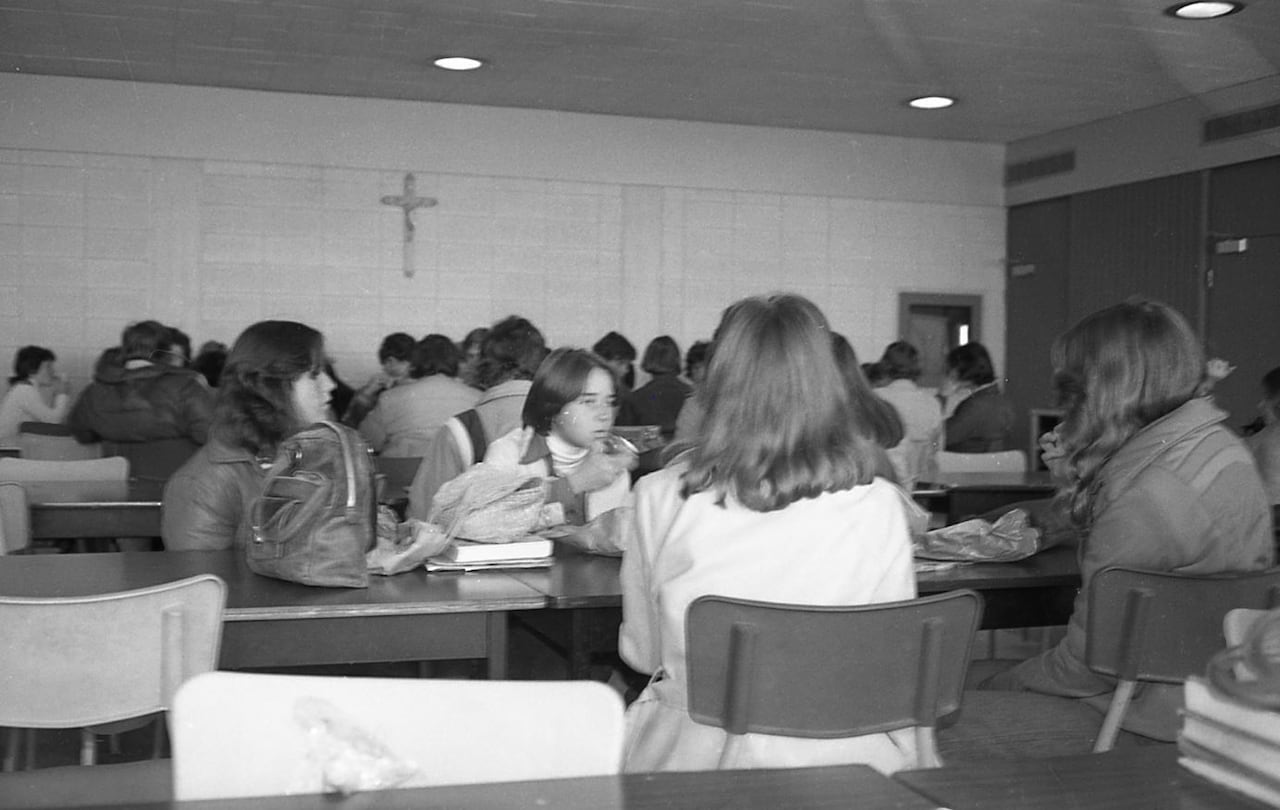

St. Pius began its life as an all-boys school and only became co-ed in the early 1970s.

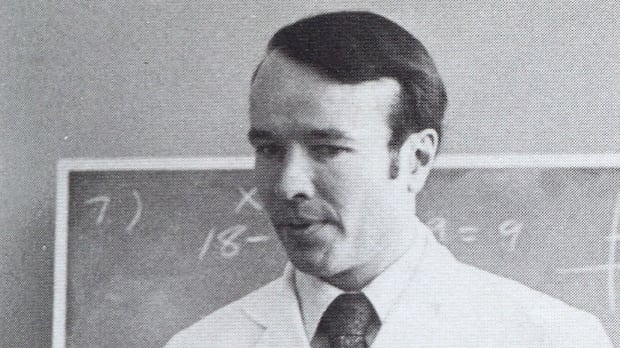

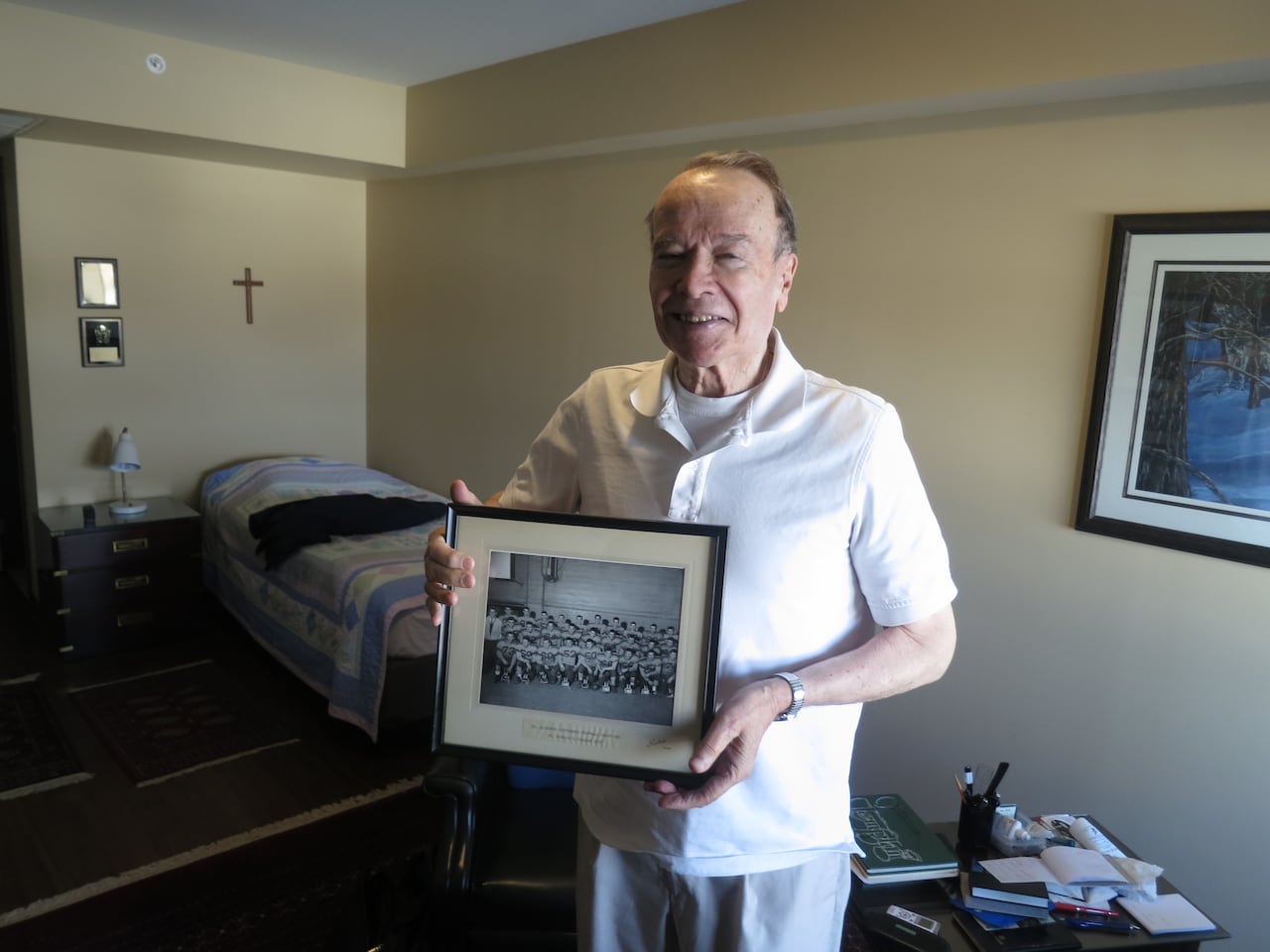

Many of its teachers were priests and nuns, as was the case with the religion class taught by Father Bob Bedard in Classroom 71.

Students describe Bedard as a charismatic speaker who didn’t shy away from topics like sex and girls. He lived at the school too, and Vanden Hanenberg considered him a second father.

“It wasn’t a class you wanted to miss,” Vanden Hanenberg says.

(St. Pius X High School yearbook)

When the door burst open on Oct. 27, some turned to see Poulin holding his sawed-off shotgun.

“I never looked, thankfully,” says Michael Monette, “because people said that face has haunted them for a long, long time.”

Monette, an engineer and corporate executive who recently retired as an international document and information systems expert, was only 16 at the time, making him one of the youngest students in Bedard’s class.

He rushed home, where his mom, “a proper British woman, God rest her soul,” wanted to know why he wasn’t at school. She didn’t believe his story about a shooting. His friends backed him up.

“She said, ‘OK, I’ll go put the tea on,'” Monette remembers.

Monette says he should have been hit by the second shot — the one fired after Mark Hough, who was just behind him, was struck in the head.

“I wonder sometimes, quite frankly — and this may seem a little bit odd — but was it the hand of God that saved me? That there [was] more things for me to do in my life?”

Anne McGrath, who went by the first name Geri then, was in the classroom too. She was standing when Poulin opened fire. Someone yanked her down by her hair.

After Poulin went into the hall, students smashed the windows with desks to escape.

“But I thought ‘they’ were shooting from the outside,” McGrath said via email. “I thought maybe ‘the war’ had started.”

When she got home, McGrath was too afraid to shower despite the blood in her hair and stayed sitting up in bed all night with the lights on. “I couldn’t speak and I was afraid to close my eyes,” she wrote.

Shawn Charland, a Grade 10 student and 14 years old at the time, was in the cafeteria. He didn’t even hear the shots.

But through the doors he saw teacher Dave Albert, unmistakable in his white lab coat, staring down the hall at something with his mouth open.

Another teacher rushed to close the cafeteria doors, tears streaming down his face, and shouted for students to “Go home!”

Forty-one years later, in 2016, Charland would finally fill in the blanks. He’d befriended the elderly Albert and began taping their conversations about life at St Pius.

Twice, the talk turned to the day of the shooting — and Charland was astonished to hear Albert say he witnessed Poulin taking his own life.

Albert also spoke about rushing to the classroom when it remained unclear whether there was another shooter, and about posting someone at the door of Classroom 71 because he didn’t want the traumatized students inside to see Poulin’s body.

Albert died in 2021, but Charland has allowed CBC to share portions of their conversations to “mark the sacrifices that were made by people who didn’t look for the limelight.”

Student body president Marc Arsenault was among those whose well-being Albert had in mind. Arsenault spoke to CBC’s As It Happens on the day after the shooting.

“I didn’t stop to stare at it or anything,” Arsenault said of rushing past Poulin’s body. “[I] probably would have been sick if I had.”

But when pressed for details about Poulin’s motive, Arsenault could only guess.

“Well, he’s gone here for five years and, like, from my experience, anybody that goes to this school for five years doesn’t hold anything against it.”

The president of the student body at St. Pius X High School in Ottawa spoke to CBC’s As It Happens on the day after the October 1975 shooting that left several classmates wounded. (Thumbnail photo: City of Ottawa Archives, Ottawa Journal, 028400)

Grade 12 student Bob Davidson was in the room next door when the shots rang out.

He gravitated to the broken windows of Classroom 71 and says a strange sense of calm overcame him as he helped lift the stretchers.

“It was my first exposure to critical-incident stress, for sure,” says Davidson, whose experience that day led him to become an Ottawa paramedic for over 40 years.

Bob Davidson says a strange sense of calm overcame him when a shooting broke out at Ottawa’s St. Pius X High School in October 1975. The experience led him to become a paramedic, a job he went on to do for over 40 years. (Videography and editing by Mathieu Deroy. Set design by Michel Aspirot.)

Dennis Curley, the psychotherapist, fled across the street to a stranger’s house, called the police, and then went back to the school.

He remembers one of the wounded telling him to calm down:

“Dennis, it’s going to be OK.”

One day after Grade 13 student Robert Poulin of St. Pius X High School in Ottawa opened fire on his religion class, the principal of the school, Father Len Lunney, spoke to CBC about the incident.

Back to school the next day

When it came over the radio that officials wanted students to return to St. Pius the very next day, Curley thought they were crazy.

“Why would you want to bring us back to that place?” he said he thought at the time.

Bedard wanted to shut his classroom down for a couple of days, but as he wrote in memoirs published the year before his 2011 death, “[Lunney] and [the] guidance head wouldn’t hear of it.”

Pat Jennings also taught in Classroom 71 and says he was back in there on Oct. 28. The windows were replaced, the room cleaned up overnight.

During evening football practice, Jennings remembers thinking, “What are we doing out here?”

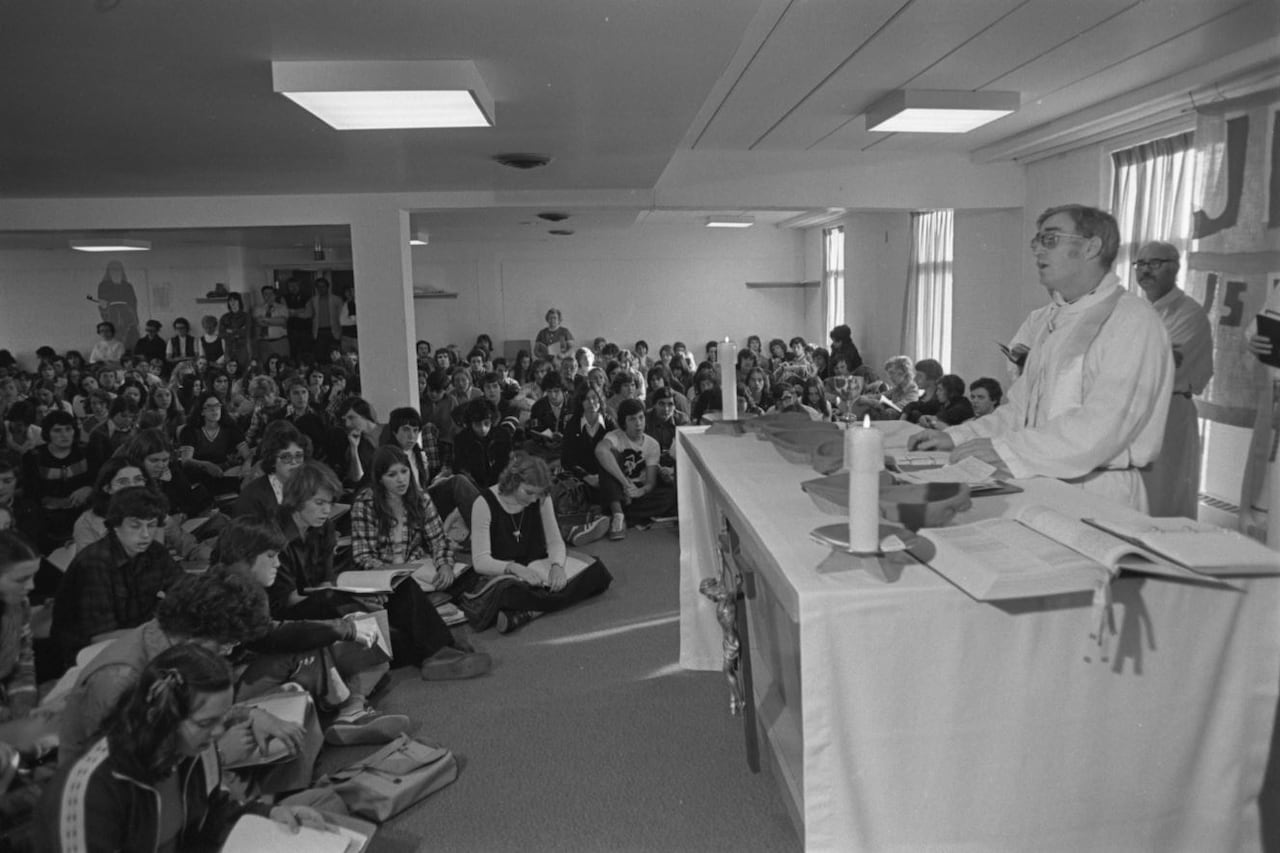

Lunney led a mass that day, like the school did every day.

Davidson says there wasn’t the modern crisis response people might expect today, “but just the fact of being able to get together with everybody was a powerful thing.”

Curley agrees — “You can’t sit at home and wallow in this thing,” he says — adding that now, in retrospect, he thinks the school was right to call kids back.

“To criticize what the school did at the time, that’s bogus,” says Lunney’s nephew Mike Nugent, who began his teaching career at St. Pius only that September.

A psychiatrist was consulted to help steer staff through the difficult days ahead, according to both Jennings and Nugent, while Curley recalls coffee and doughnuts being rolled into his class and students being encouraged to talk.

Others have serious misgivings about how the aftermath was handled, though.

Claire Turenne-Sjolander, a Grade 12 student at St. Pius in 1975, wrote in a 2011 collection of essays called The Militarization of Children that she felt a “Herculean” effort was made “to ensure that everything returned to normal as quickly as possible.”

“You have a timetable. Follow it,” Lunney told students, according to the Ottawa Citizen, which covered the mass despite some students wanting them ejected.

Anne McGrath, who felt like a zombie upon her return to school, says she, too, sensed pressure from the school to move on.

“Several students and Father Bedard became ultra-religious and, in my view, evangelical that year,” she wrote in her email to CBC.

“It was enraging to me. I left the church when I was in university and I’m an atheist.”

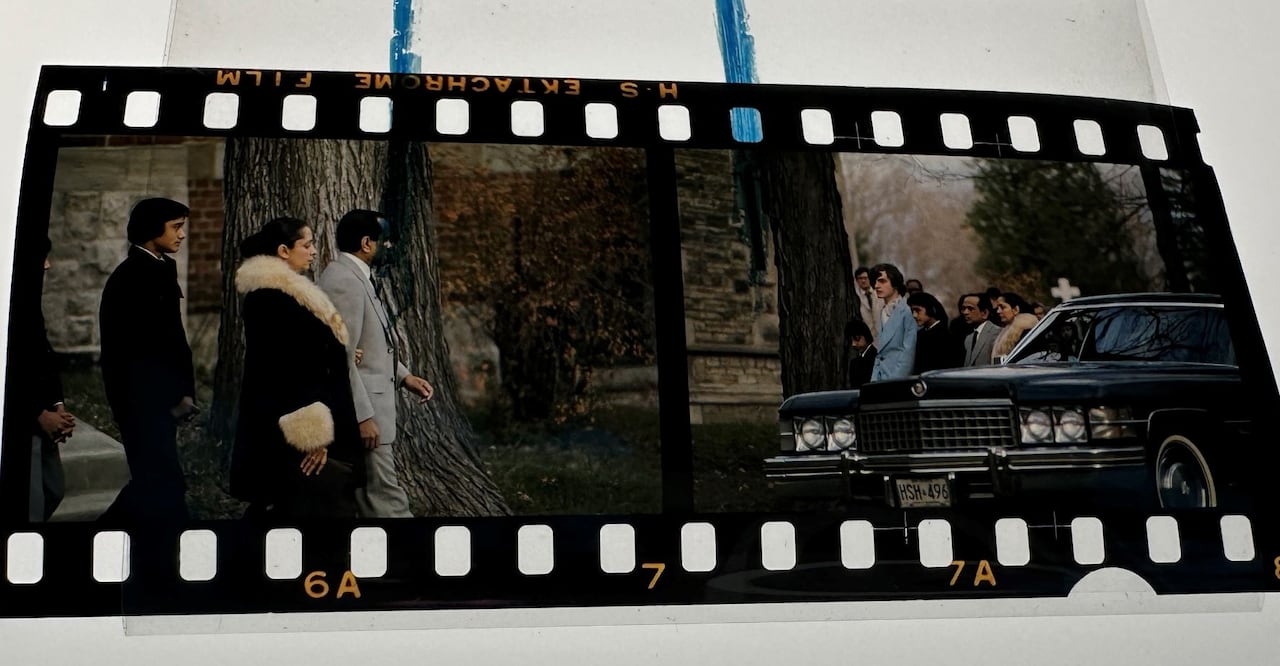

The family of Kim Rabot, the Glebe Collegiate Institute student Robert Poulin murdered at his house before the shooting, buried her on Oct. 30.

Then came a coroner’s inquest in early December, which began with the announcement of shooting victim Mark Hough’s death. Attendees and witnesses, including several students, were then exposed to a barrage of disturbing details about Poulin.

“It was like you were in a horror film, except it was real,” says Liam Maguire, Hough’s busmate.

Says Curley of what happened to Rabot: “It allowed me for moments to not think about me.”

Michael Monette remembers the school pairing him with a psychologist who helped him unpack what the inquest revealed.

“I thought back to when I saw Robert sitting in one of the chairs. And I’m there. We’re these quiet kids. One starts to think, ‘Could I be like that?’ And the psychologist was excellent in terms of helping me gain knowledge in terms of normal behaviours,” Monette says.

“It settled my mind about, OK, I know who I am. What happened here was clearly very different, and I had a sense of how I could go forward in my life.”

Terry Vanden Hanenberg says when he was released from the hospital and went back to school, the shooting had receded into the background.

“I don’t know if it was on purpose that it was kept quiet, or people were afraid to talk about it, but it was not talked about when I was there,” he says. “Even with Father Bob, as close as I was to him, we never sat down and had a heart-to-heart about what my thoughts were.”

Maguire says that by his Grade 12 or Grade 13 year, “it was almost like it didn’t happen.”

In an emailed statement, the Ottawa Catholic School Board (OCSB) says that if such a tragedy were to occur today, “our response would be very different” and that it regrets those supports were not in place in 1975.

“We now have crisis teams, mental health professionals, and chaplaincy leaders who provide immediate and ongoing support, and we work alongside families to decide how best to honour a student’s life,” according to the statement.

‘Time heals’

For a long while after the shooting, when sitting in a room, Monette would position his back to the wall so he could see the door.

There was a time, he said, when talking about the shooting would provoke an emotional response. But not anymore.

“The years, and I would say time, heals. Memories fade, and their severity can [too] for some people,” Monette says.

Students and educators in Ottawa react in 1999 to the Columbine massacre in Littleton, Colorado.

When Curley would hear a car backfire, he’d hit the ground.

“Your subconscious rises to the occasion to actually protect you from the damage of what happened. The problem is, we learn to live with it and it becomes part of our own psyche,” he says.

It was after his breakthrough at the school on the 40th anniversary that Curley became a psychotherapist himself.

“I wanted to help people who’ve been through [incidents like mine],” he says.

McGrath went on to become a senior political operative for the federal New Democratic Party.

On Oct. 22, 2014, she was at the front table of the NDP caucus meeting when the Parliament Hill shooting unfolded.

“When I was lying on the floor … shaking with fear, I couldn’t believe that this could be happening again,” McGrath wrote.

Sometimes, she thinks people on the street have a gun in their pocket. “I brace my body for gunshots, but try not to look. Because I’m aware that it’s weird.”

In June 2016, St. Pius had to be placed on lockdown after a report of two hooded kids wearing masks running toward the school — only two days after the Pulse nightclub massacre in Orlando, Fla.

The school board later confirmed two Grade 12 students had entered the school with air horns and a box of crickets.

Two days after the horrific Orlando nightclub massacre in 2016, St. Pius X High School went into lockdown after a neighbour spotted two teens wearing masks headed toward the school. Police learned it was a terribly-timed graduation stunt.

Maguire says students who attended St. Pius in the more immediate wake of the 1975 shooting had their own version of that.

There was a bomb scare during exams, he says.

“It was pins and needles for a few hours, I can tell you, because it just evoked all the chaos from the shooting.”

(Mathieu Deroy/CBC)

Vanden Hanenberg says he’s gone on to have a good life: a wife, two kids and a nice home. “I have no complaints,” he says.

But the shooting probably comes up on a weekly basis.

“Even after 50 years, it still seems to always rear its head,” he says.

While the Ottawa Community Foundation and Glebe Collegiate Institute have quietly paid tribute to Kim Rabot every year by giving out an award in her honour, there is no memorial to the larger events of Oct. 27, 1975 — not at St. Pius, not anywhere in Ottawa.

Bill Shepheard, who was an Ottawa police constable in his 20s when he responded to the call about the shooting, fears it may be too late.

“Too many people, 50 years later, don’t know what we’re talking about,” he says.

‘You can’t rewrite history’

That didn’t stop organizers of a memorial erected in 2017 to mark the fatal shooting that happened at Brampton Centennial Secondary School in May 1975 — only five months before the St. Pius attack.

Curley thinks there should be something similar at St. Pius.

“You can’t negate what happened. You can’t rewrite history. They’re not trying to do that. But we can’t push it down either,” he says.

Vanden Hanenberg says that if there’s anything to be done, it should be for Rabot and Hough.

“They’re the ones that didn’t survive this. I’m fortunate that I did and I’m happy for it. But I won’t celebrate it, that’s for sure.”

In its statement, the OCSB said that after careful consideration this summer, it decided the school would not host any anniversary activities or memorial events.

“Our current student population is highly diverse. Many have come to Canada from communities marked by violence and displacement,” the board said.

“For these young people, even historic tragedies can reopen wounds and compromise their sense of safety.”

On Sunday, Hough’s family gathered at a bench along the Rideau Canal that they had dedicated to him earlier this year.

Vanden Hanenberg, Maguire, Jennings, McGrath, Charland and a number of other St. Pius alumni attended a memorial mass at St. Maurice Parish.

And on Monday — 50 years to the day Rabot, Hough and Poulin died — Fred May, a classmate of Rabot’s who helped launch her memorial award, will stop by her gravestone at Beechwood Cemetery and play one of their favourite flute pieces from his phone.

“There are lovely old maple trees near the grave, which are pretty close to eternal in my books,” he says.

This story is the final installment of a four-part series.

Part 1 examined the events of Oct. 27, the coroner’s inquest, the debate about gun control and the experience of the Poulin family. Click to read the story here.

In October 1975, two Ottawa high schools were rocked by murders committed by a troubled student who then took his own life. As the anniversary approaches, CBC is looking back at the changes, both personal and societal, that took place in the event’s wake. (Videography and editing by Mathieu Deroy. Production design by Michel Aspirot.) (Thumbnail photo: City of Ottawa Archives, Ottawa Journal, 028395)

More on the larger story from CBC’s This Is Ottawa podcast:

Part 2 remembered Kim Rabot. Click to read the story here.

Seventeen-year-old Kim Rabot was the first murder victim in a tragic series of events on Oct. 27, 1975, that culminated in a fatal shooting at an Ottawa high school. For the last quarter-century, one of Rabot’s friends has worked to ensure she is remembered as more than just the victim of a heinous crime. (Videography and editing by Mathieu Deroy. Production design by Michel Aspirot.)

Part 3 honoured Mark Hough. Click to read the story here.

After he murdered a student from another school at his home on Oct. 27, 1975, the perpetrator opened fire on his religion class at Ottawa’s St. Pius X High School, wounding 18-year-old Mark Hough. Hough died in hospital just over a month later. Five decades later, his family is opening up about what happened next. (Videography and editing by Mathieu Deroy. Production design by Michel Aspirot. Additional videography by Francis Deschênes.)

If you or someone you know is struggling, here’s where to look for help:

If you’re worried someone you know may be at risk of suicide, you should talk to them about it, says the Canadian Association for Suicide Prevention. Here are some warning signs:

- Suicidal thoughts.

- Substance use.

- Purposelessness.

- Anxiety.

- Feeling trapped.

- Hopelessness and helplessness.

- Withdrawal.

- Anger.

- Recklessness.

- Mood changes.

Producer: Jen Beard

Videography and editing: Mathieu Deroy

Production design: Michel Aspirot

Copy editing: Alistair Steele and Trevor Pritchard

Thank you to everyone who shared their stories (or made it possible)