Premier François Legault’s fiery promise to defend Quebecers from “radical Islamists” by banning prayer in public has reignited a debate that has dominated the political agenda in the province for the last 20 years.

In a speech to open the latest session at the National Assembly last month, Legault talked about a threat to Quebec’s identity from what he called “politico-religious” groups.

“I’m talking about radical Islamists, a group of people who try by all means to impose their values, to challenge our values and in particular women’s right to equality,” Legault thundered in the National Assembly.

Not to be outdone, the Parti Québécois, which leads in opinion polls under leader Paul St-Pierre Plamondon, not only supports the Coalition Avenir Québec (CAQ)’s prayer ban but has also proposed prohibiting elementary school students from wearing religious symbols.

“What you’re seeing now is a competition between the two nationalist parties to see who’s willing to go furthest in passing illiberal policies to make it more and more difficult for minorities to choose to be different,” Stephen Brown, president of the National Council of Canadian Muslims (NCCM), told CBC in an interview.

The promises are just the latest in a series of escalating secularism measures that have been proposed and debated in Quebec since the early 2000s.

And with Quebec’s current secularism law, Bill 21, being challenged before the Supreme Court of Canada and an election campaign coming next fall, the debate is not likely to end soon.

How it started

The roots of the secularism movement in Quebec date back to the 1940s and ’50s, when the Catholic Church wielded tremendous social and political influence.

The church, which ran schools and hospitals, was basically interwoven with government, and dictated many moral standards.

For the last 20 years, one issue has kept resurfacing in Quebec politics. It’s not language or separatism, but the relationship between Quebec society and religion — often one religion in particular.

In the ’60s, Quebecers pushed back in what became known as the Quiet Revolution.

“The Catholic Church had dominated the relationship between couples at the time. And there was a sort of a reaction to all of that,” John Parisella, former chief of staff to Quebec premier Robert Bourassa in the early ‘90s, told CBC in an interview.

“Nobody wanted the Catholic Church to be telling them what to do, who to marry and how many kids you’re going to have,” Parisella said.

The provincial government gradually assumed control of health and education, and the church’s influence waned as Quebec modernized.

As debates over independence dominated in the ’70s, ’80s and ’90s, the issue of secularism receded.

The 2nd wave

That all changed Sept. 11, 2001.

The attacks on the World Trade Center in New York triggered backlash against Islam around the world, but the focus in Quebec was particularly acute because of its history with the Catholic Church.

In the years following 9/11, media outlets in Quebec began spotlighting – often with sensational headlines – what became known as the “reasonable accommodation crisis,” focusing on concessions made for religious groups.

A notable example was a sugar shack that altered its menu and converted its dance floor into a prayer space to accommodate Muslim visitors, sparking outrage.

“Quebecers in the regions decided that special accommodations done for different religious groups was something they didn’t want to go into,” Parisella said.

“They lived it with the Catholic Church … and decided that they didn’t want it to be brought in through other religious groups.”

In 2007, the town of Hérouxville made headlines around the world when it adopted a controversial “code of conduct” for its non-existent immigrant population, banning practices like stoning women and genital mutilation.

This sparked the Bouchard-Taylor Commission, which explored reasonable accommodation and made several recommendations in 2008 that were largely forgotten, ignored or modified by subsequent governments.

In 2013, a minority PQ government proposed the notorious “charter of Quebec values,” aiming to ban religious symbols for public servants, but it went nowhere after the PQ lost the 2014 election.

The Liberals under Philippe Couillard tried their own compromise in 2017 with Bill 62, requiring face coverings to be removed when accessing public services, which faced legal challenges.

The reigning CAQ government, which was elected before there was a final decision on that bill, took its own stab at legislating secularism, reviving a watered-down version of the charter of values, which eventually became Bill 21, Quebec’s current secularism law.

Learning from previous projects, the CAQ tried to make Bill 21 legally bulletproof by preemptively using the constitutional notwithstanding clause to override certain sections of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

How it’s going

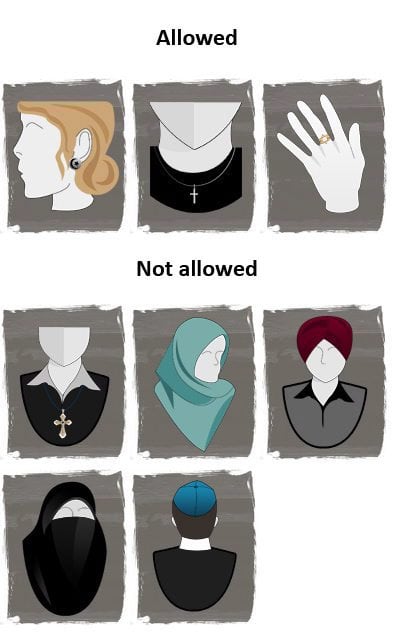

Bill 21, which became law in 2019, prevents some public servants, including judges, police officers, prosecutors and teachers, from wearing religious symbols while on the job.

The CAQ government has repeatedly called Bill 21 a reasonable compromise, claiming after it was adopted that it had mostly settled the debate over secularism in Quebec.

But the bill’s preemptive use of the notwithstanding clause is being challenged in the Supreme Court of Canada, and the CAQ has continued to propose increasingly restrictive measures to enforce secularism that go well beyond Bill 21.

The controversy over a toxic work environment with tensions between Muslim and non-Muslim teachers at a Montreal elementary school last fall once again put secularism on the front burner.

Last spring, the education minister introduced legislation that would extend the ban on religious symbols to include not just teachers but all people who work in schools – including lunch and after-school care monitors, and even volunteers.

In August, an advisory committee appointed by the CAQ made several recommendations to go further, including extending the religious symbols ban to subsidized daycares and requiring people to uncover their faces when receiving public services.

Secularism versus laicité

One reason for secularism’s endurance as an issue is that most Quebecers feel passionate about it.

“Quebecers are generally very favourable to the idea that the state and church need to be separate, and that’s been the case for decades,” Sébastien Dallaire, executive vice-president of Leger Marketing, told CBC in an interview.

The concept of secularism is also different in Quebec compared to the rest of Canada.

Pearl Eliadis, a human rights lawyer and associate professor at McGill University, told CBC in an interview that secularism isn’t even really the right word to describe what’s happening in Quebec.

“I think it’s become this much more muscular idea of, in French, laicité,” Eliadis said.

The words are often used interchangeably but they have slightly different meanings.

Where secularism traditionally refers to separation of church and state, laicité takes it a step further and is really about separating religion from the public sphere.

“We have two very different concepts that don’t mean the same thing, that imply different rights and freedoms and that imply a very different role of the state that I think is partly grounded in Quebec’s history,” Eliadis said.

A convenient political tool

Some say the persistent push for secularism has less to do with history and protecting Quebec values than with cold political calculation.

“The motivation for Bill 21 was never actually to come to some sort of a societal compromise. The goal was always to get votes,” NCCM president Brown said.

Dallaire from Leger Marketing said politicians often use secularism as a so-called “wedge issue.”

“Because of its power to inflame debate, it can really put your opponents on the defensive, because then they have to justify defending policies that may not be that popular,” Dallaire said.

And talking about secularism can be a great way for politicians to distract from other issues, according to experts CBC spoke with.

Brown said that’s exactly what’s happening with the CAQ.

“They tried to address the teacher shortage. They failed. They’ve tried to address the cost of living. That hasn’t worked. They’ve tried to address the fact that we’re missing doctors and nurses. That hasn’t worked out. They’ve tried to stimulate the economy by attracting foreign investment in key industries. That hasn’t worked,” Brown said.

“What has worked is passing policies to target the rights of minorities.”

Not without risk

Dallaire warns using secularism as a political tool also has its limits and can backfire.

“If we go back to 2014, the idea of the charter [of] values was popular with most voters in Quebec,” Dallaire said. “And yet when the PQ ran on it, it didn’t really work.”

The PQ lost the election that followed.

“Those explosive issues, they become very interesting … because they have the power to shake up things,” Dallaire said. “But they also have the power to sometimes explode in your hands.”

He also noted that while secularism is popular in Quebec, it’s not necessarily something Quebecers are particularly worried about, saying it falls “pretty low” on the priority list for most.

Even Daniel Turp, former PQ MNA and current president of Droits collectifs Québec, a group that supports Bill 21, says there may be limits to pushing secularism.

“There’s always politics involved when you draft bills and have laws adopted,” he said.

“And those who try to mark points or go too far, well, they’ll lose points.”

Quebec Muslims feel alienated

Legault has always said that he sees secularism as a shared value that unites Quebecers and is embraced by a majority of the population, but many people feel alienated by his government’s policies.

“I think a lot of Muslims are feeling that Quebec is becoming xenophobic,” Farida Mohamed, former president of the Montreal chapter of the Canadian Council of Muslim Women, told CBC in an interview.

“It’s causing feelings of uncertainty. It’s causing feelings of well, maybe we should leave Quebec and go elsewhere in Canada.”

Brown said the Quebec government should realize Muslim Quebecers, who mostly come from francophone countries, could be an important ally in a province that wants to preserve French language and culture.

“We were told that we were equals and that we would be able to contribute to society and benefit from society the same as everybody else,” Brown said.

“And what we’re seeing is the people that are supposed to be representing us and our leaders are telling society that we’re dangerous and we don’t share their values.”

Eliadis, the human rights lawyer, believes that in aggressively pushing secularism, Quebec may end up right back where it started before the Quiet Revolution.

“The Roman Catholic Church and its dominance in Quebec society was a kind of isolation for Quebec,” Eliadis said.

“And what’s happening now is a use of laicité and secularism to create a new isolationism.”

Where it’s going next

One thing that could either help settle the debate — or perhaps exacerbate it even further — is the Supreme Court ruling on Bill 21.

“I think it’s going to be a historic moment in Canadian history and in Quebec history,” Eliadis said.

Arguments in the case are to be heard sometime next year, but it’s not clear if a decision will come before or after the provincial election next fall.

The CAQ, perhaps in anticipation of the Bill 21 ruling, is now proposing Quebec draft its own constitution that would defend Quebec values.

It’s hard to say when, or if, this debate in Quebec will ever end.

“You know, in France, secularism in principle was implemented in 1905, but there’s still some debate in France,” said Turp, whose group is intervening in the court challenge against Bill 21.

“So yeah, it might continue in Quebec,” he added with a chuckle.