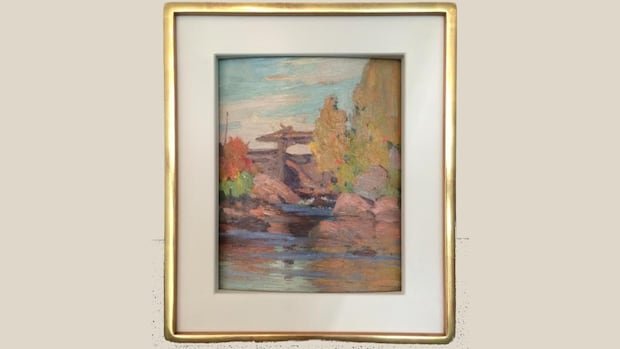

It’s been about a decade since Michael Murray saw the painting of the Tea Lake Dam he received from his uncle in 1977, a piece he says is a Tom Thomson original and whose disappearance sparked an $11 million lawsuit with a Toronto auction house that claims it never accepted the supposed masterpiece.

A gift after Murray’s medical school graduation, the painting hung in his uncle’s home in Ottawa, a property he inherited from Flora Scrim, the owner of a local flower shop where he worked. The painting came with the property and Murray says it is believed to have been a gift to Scrim’s brother from renowned Canadian painter Tom Thomson.

Michael Murray is suing Waddington’s Auctioneers & Appraisers of Toronto, alleging conspiracy and negligence in connection with the disappearance of his painting which he claims is a Tom Thomson original. CBC’s Farrah Merali has the story.

But while he can trace how the 8×12-inch painting came into his family’s hands, neither Murray nor a private investigator can find what happened to it, they say, since it was sent to be sold at Waddington’s Auctioneers & Appraisers.

“I felt stupid, taken advantage of,” the 74-year-old told CBC News in a recent interview.

The lawsuit alleges that the painting’s disappearance was caused by “gross negligence” and alleges that the auction house and a former employee “conspired with each other” to hide the painting from Murray.

None of the claims have been proven in court. In its defense statement, Waddington’s denies the allegations and claims the painting was never at the auction house. He also questions the authenticity of the painting, which is a small, colorful landscape believed to depict the Tea Lake Dam of Algonquin Park in Ontario.

Change of hands

Murray told CBC News that he and his wife decided to sell the unsigned painting more than a decade ago and began the process to authenticate it. In 2013, Murray, who works as a doctor in Hawaii, sent the painting to the National Gallery in Ottawa for review by the University’s conservation sciences division. Canadian Conservation Institute.

Staff analyzed the painting and found a pigment called “Freeman’s White,” a pigment that has only been found in paintings by Thomson and the Group of Seven, according to the staff report, which was viewed by CBC News.

“This strongly supports the attribution to Tom Thomson,” the report reads.

According to the statement of claim, in April 2014 the painting was also examined by an art historian at the University of Toronto, who attributed it to Thomson. In the summer of 2014, according to the claim, the painting was sent for restoration and then given to Toronto’s Nicholas Metivier Gallery in July 2014.

Gallery owner Nicholas Metivier, who declined to speak to CBC News for an interview, recommended Waddington’s services in Toronto in 2015, Murray told CBC News. Metivier also introduced him to Stephen Ranger, at the time the auction house’s vice president of business development and an appraiser, he said.

“They were all credible references, every step of the way,” Murray said.

Murray said he exchanged emails with Ranger, in which Ranger agreed to handle the sale at a fall 2015 auction, but Murray said he did not receive any official documentation from Ranger or Waddington’s.

The statement of claim says Murray inquired about progress with Ranger, who “consistently” confirmed the painting was at Waddington’s, but then in 2017, Murray was told the painting would be placed in temporary storage. Murray told CBC News he didn’t contact Waddington’s for a few years due to health issues in his family.

In 2021, after Murray claimed he made “numerous” inquiries to Waddington’s, he received an email from a representative of the auction house stating that the painting was not there.

“It took me a long time to sink in,” Murray said. “I was thinking, ‘Where is my painting?'”

Appraised at $1.5 million

In early 2022, Murray contacted Steven Bookman, managing partner at Bookman Law, for help.

“There is strong written evidence through emails and other communications that it was in [Waddington’s] possession,” Bookman said in an interview with CBC News.

“We have very little concern about establishing the validity of this as a real Tom Thomson.”

That same year, Murray hired an appraiser to review available documentation related to the painting and appraise existing photographs. The appraisal report, seen by CBC News, estimated the painting’s value at $1.5 million.

“The last value we had was in 2022. These Tom Thomson paintings are in incredible demand, so I don’t know if it has increased since then.”

Waddington’s response

CBC News contacted Waddington’s and its president Duncan McLean and received a response from their lawyers saying: “As this matter is currently before the courts, we are unable to comment at this time.”

However, in a statement of defense filed in response to Murray’s lawsuit, Waddington’s denies that the painting was ever in its auction house, saying that when it takes possession of any work of art, it provides a receipt and enters that data in your system.

“No such records exist for the painting,” the statement said. “To the defendant’s knowledge, the painting was never stored at the Waddington premises.”

The defense statement also denies that the painting is by Thomson or that it “has any real monetary value.” It claims Waddington’s and McLean made inquiries about the painting in July 2021 and were informed by “external authorities” that it was not authenticated as Thomson’s work.

In court documents, Waddington’s alleges it learned in 2020 that Ranger was running his own business in competition with Waddington’s and that his employment was terminated, claims that have not been verified by CBC News. When contacted for comment via email, Ranger told CBC News: “I left Waddington’s five years ago, so I had no idea of the whereabouts of this painting.” He did not respond to a new interview request.

However, in his defense statement, Ranger said he collected the painting in his capacity as vice president of Waddington’s and says he delivered it to Waddington’s. He claims the painting was still in Waddington’s possession in storage at the time of his departure in February 2020. The defense brief goes on to say: “At no time [he] remove, sell or dispose of paint from Waddington’s premises.

‘Opaque’ industry and challenges

In 2021, Murray hired Haywood Hunt and Associates to try to locate his lost painting.

“People who may have possessed that painting at some point were not eager to admit that they had the painting,” said Jeff Filliter, lead investigator for the private investigation agency and leader of the case.

“Some of them grudgingly said, ‘Yeah, we had it for a while, but it’s gone.’ So the challenge was trying to pinpoint precisely when the painting went from point A to point B to point C.”

Filliter said what caught his attention was the lack of enthusiasm among many to share information.

“It got to the point where when we were talking about possession of the painting, everyone was throwing up their hands and saying, ‘No, it’s not me, it’s not me,’ which I thought was a little strange,” Filleter said.

He said he made inquiries about a possible sale of the painting on the dark web or black market, but to no avail.

“As time goes by, it becomes much more difficult to find an object because of the elusive nature of the art market, because of its opaque nature,” said Det-Const. Lionel Doe of Toronto Police Services. Doe is not involved in the civil suit, but he completed a graduate program in art crimes in Italy, the only member of the police service with such training.

“If there is no paper trail or a vague paper trail to follow, adding more time to it makes it much harder to find.”

But in certain cases, Doe says the passage of time can help recover a stolen painting, although it has not been proven that Murray’s painting was stolen on purpose.

“If it’s a high-end painting or a masterpiece, it appreciates at a level that will eventually force it to the surface because of the temptation to sell it,” Doe said.

A trial date has not yet been set for Murray’s lawsuit, which was filed in the Ontario Superior Court of Justice in March 2022.

While Murrray said he regrets not asking Waddington’s for more documentation at the time, he said he felt confident that at every step he was referred from one credible expert to another, and said he’s not sure what he could have done differently. .

“I was very confident that I was dealing with honest and direct people,” Murray said. “I feel betrayed.”

If you have tips for CBC Toronto’s investigative team on this story or others, please contact torontotips@cbc.ca