When Paul Sanborn began investigating the next federal elections, he felt dismayed when he learned that he had moved to a new electoral driving to which he feels very little connection, and what worries him will not represent his views.

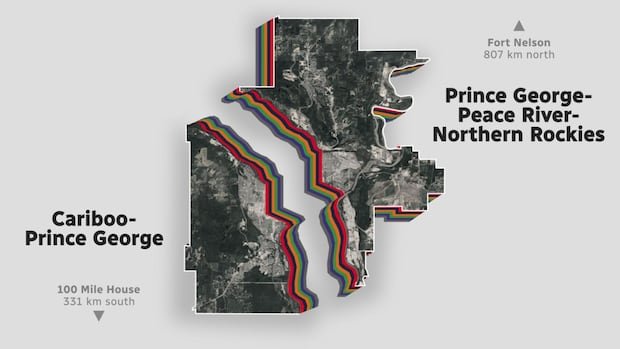

Prince George resident, BC, had previously been at the northern end of Caribo-Prince George, which extends approximately 300 kilometers south to pass the 100 mile community.

But as part of a redistribution process, it had now been transferred to the southwest corner of the driving of the George George-Peace-Northern river, which extends approximately 250 kilometers southeast to the Albert Forthleon.

“Maybe he was being a bit grumpy but, you know, it seems strange that we [the city of Prince George] It is still cut and cut into cubes in a different way every few years, “he said, adding that he would like to see the city becoming his own independent driving.

Sanborn says that while he feels that there is a natural connection between Prince George and the other communities in his old driving, particularly with the importance of forest industry in the region, there is very little to link it to voters in the northeast of the province, where many people work in oil and gas and have strong links with Alberta.

“There is a social and economic flavor in this area that distinguishes it from the northeast of British Columbia, so for me it really makes no sense to put them in the same constituency,” he said. “I would like to see a more rational limit.”

What Sanborn faces is what those responsible for creating electoral limits throughout the country call “the challenge of British Columbia”: the process of trying to create approximately equal populations cabins in a vast and varied geography.

And open questions about whether the current electoral system goes far enough to guarantee precise representations of the wishes of the voters.

An urban-rural division in the north?

One of the most obvious examples of this complaint inside and northern BC can be seen by observing the results of the federal elections of 2015.

That year, like any other election year before it returned to 2004, the conservatives swept the majority of the region, including the cities of Kamloops and Prince George.

But a closer look at the data surveyed shows that the liberal candidates were preferred by little voters in each of those cities, while a stronger conservative preference was recorded in the peripheral regions, allowing the candidates of the party to win.

Tracy Calogheros was the liberal candidate for Caribú Prince George and says it is frustrating to know that he had connected with the voters in the largest city in his region, but could not represent them.

“You end up losing an urban central voice in the north because it is diluted in such a large and rural area with very different problems,” he said.

And Trevor Bolin, a member of the Conservative Party at Fort St. John, who could see his deputy to the election go to Ottawa, feels in the same way.

“I think it’s too big,” he said about the driving he shares with Sanborn, 400 kilometers by car.

“For one [candidate] To try to represent from the border of the territories to Prince George … we have great differences between our communities that need our own representation. “

How waves work

In Canada, the country is divided into 343 different cables or electoral districts. Each of these cables celebrates its own choice, with the residents casting their vote by a single person to represent them in Ottawa as their member of Parliament or MP. The prime minister is generally the leader of any party who has chosen most parliamentarians, although that is not always the case.

Look | How the elections work in Canada, explained: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ttwi3hjzsxi

As a general principle, Canada aspires to each vote that has equally. For that to happen, each MP needs to represent approximately the same number of people.

Then, as the populations of some regions grow and others shrink, the borders of assembly become written every 10 years in an attempt to achieve the parity of the population.

That work is carried out by an independent and non -partisan commission in each individual province, with comments from politicians and the public.

British Columbia challenge

Stewart Perst, a political scientist from British Columbia University, says that while commissions try to adhere to the beginning of “a person, a vote”, they also take into account other factors.

“They are also considering how to keep historically significant communities,” he said. “And try to guarantee that the limits are, in a sense, a manageable geographical size … that is not a feat.”

During the most recent redistribution, the BC commission identified two key issues, which called “The British Columbia Challenge”: the “unequal distribution of the population” of the province and its “varied and resistant physical geography.”

For geography, the commission mentioned the mountainous chains, rivers and oceanic barriers that prevent certain regions from being easily combined in a single electoral district.

And for the population, he pointed out that the vast majority of people in BC live in the southwest, concentrated around Vancouver and Victoria, while the north and interior are much more scarce.

As an example, only three currents, Skeena-Bulkley Valley and the two currents of Prince George, occupy about 70 percent of the geography of the province, a larger land mass than France or Germany. At the same time, these currents house just over 323,000 people, or less than six percent of the total population of the province.

With similar problems in other parts of the interior, and faced the objective of making an approximately equal population condition, the commission has chosen to break the three largest cities in the region: Prince George, Kamloop and Kelowna, and placing different neighborhoods in different electoral districts.

And although these cities generally show the same voting preferences as other communities in the region, the question of representation arises when, as in 2015, they vote in a different direction.

Perst said that, unlike some countries in which the parties elaborate the electoral borders that seek to give a political advantage, the Canadian system has remained neutral, with the guide light “a voice, a vote.”

And he said that while he may feel unfair to voters in Kamloops or Prince George not having a single driving that covers his needs, it is a requirement under the current voting system.

“It will always be this type of equilibrium act, and not many people will be totally happy with the result,” he said.

Calls to reform

While the voters with whom CBC News talked about this story generally agreed with the principle of “a person, a vote”, they felt that more space should be made for smaller heads in areas that cover vast geographies.

But they also mentioned another possibility: some form of electoral reform that would result in each driving that chooses multiple parliamentarians that represent different parties.

That is the preferred solution by Gisela Ruckert, a Kamloop resident and Fair Vote Canada, a national defense group that presses so that the current first -step voting system is replaced with some form of proportional representation.

She said that while alienation feelings can be acute in the north and rural mountains, they express themselves throughout the country.

“It occurs in the center of Toronto, where people who vote for conservatives have absolutely no representation,” he said.

Justin Mcelroy of CBC explains the differences between the two voting systems.

“It occurs in the center of Calgary, where people looking for an alternative to the conservative party end with zero or very little representation … and that is because our political system is designed to give space to the greatest voices at the expense of all others.”

While there are several forms of proportional representation, Ruckert said that the key point is that the result reflects more closely a diversity of opinions among voters.

Under the current system, each driving sends a single MP to Ottawa, regardless of how strictly win. However, the proportional representation directly links the percentage of votes that each party receives the number of elected representatives, which often results in multiple members of different parties in each driving and guarantees that each vote impacts that it is selected to govern.

Having an electoral map that more accurately reflects the various points of view not only in Canada, but also within the individual heads, Ruckert argues, would lead to greater satisfaction and voters and more committed candidates, since it would make each driving more competitive, and the results would reflect the nuances in the final vote.

“We would have more colors on the map,” he said. “It would not be a solid strip of blue or red or orange or whatever at a given time.”

That sounds good for Sanborn in Prince George.

“I’m not obsessive with electoral reform,” he said. “I don’t think it will make the electorate more intelligent or wiser or better behaved, but I think it would at least address silly things like having the largest city in the north cut and cut on deck.”