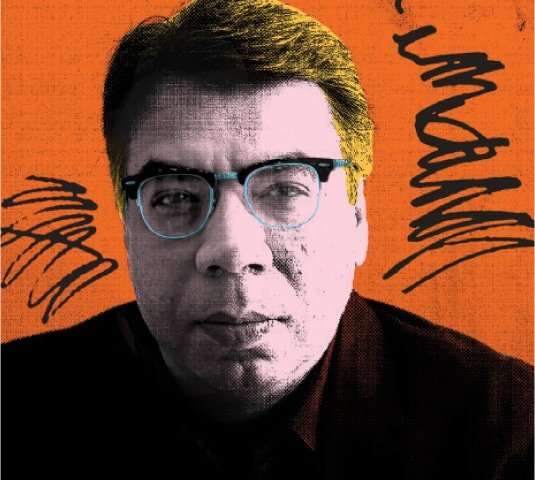

Recently, I found a miniature of a podcast presented by a well -known Pakistani journalist. The video miniature declared that an “Islamic army” had to take control of Gaza.

In fact, one of the suggestions made by several countries for US President Donald Trump is to convince Israel to withdraw his forces from Gaza and allow an international strength to maintain peace to be stated there. In fact, this suggestion is already part of the “peace plan” that Trump is offering to Israel, the Palestinians and their respective allies.

If everything goes as planned and the Israeli prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, really agrees, there is a probability that a peace maintenance force replaces Israeli forces who have flattened Gaza and killed tens of thousands of men, women and children there, both Palestinian Muslims, such as no thugs.

The peace maintenance force will probably be composed of military personnel belonging to Muslim majority countries. Therefore, it will be a Muslim force. To call it an “Islamic army” is not only problematic, but also to a large extent. Let me explain.

The constant interchangeable use of the ‘Islamic’ and ‘Muslims’ terms in public discourse has resulted in an inability between the majority to understand the important difference between the two

In Pakistan, the ‘Islamic’ and ‘Muslim’ words in most cases are used interchangeably, or as if one were the synonym of the other. At least since the early twentieth century, at the political and social level, the word ‘Islamic’ often involves clear ideological connotations, while the word ‘Muslim’ is almost completely treated cultural identity.

So, in this context, not all Muslims are ‘Islamic’ as such. There are numerous men and women who identify with Islam due to their family history, inheritance or the social environment in which they were raised. But they do not adhere or agree with the policy and practices associated with what is generally perceived as “Islamic”.

However, they are still Muslims. However, they often see the word ‘Islamic’ as a result of mixing religion with politics. Some may be completely secular and even derogatory of contemporary laws formed by particular interpretations of the Scriptures of faith by certain governments, however, they identify as Muslims and follow the basic doctrinal principles and cultural practices of Islam.

So what is ‘Islamic’? Transmitting the Qur’an through art (calligraphy) is correctly understood as Islamic art. The architecture and design that are presented as visual representations of God’s infinite nature are also Islamic. A conference in which Muslim theologians discuss the dynamics of Islam’s writings can also be called as an ‘Islamic Conference’. But a conference that is framed to generate discussions about the political and economic position of Muslim majority countries is not an “Islamic Conference.” It is a meeting of political representatives from Muslim majority countries.

The confusion in this regard only deepened when the political meetings of Muslim leaders began to be labeled as ‘Islamic summits’ or when sporting events involving athletes from Muslim majority countries are labeled as ‘Islamic games’. There is nothing ‘Islamic’ in them, unless the peaks were discussing the complexities of Islamic theology or, in the case of the latter, sporting events were remodeled by placing them in the context of Sharia [Islamic teachings].

Returning to the case of Pakistan, most of the literature produced during the height of the Pakistan movement in British India talks about Muslim nationalism. For example, the All India Muslim League (AIML), which became the greatest party of Muslim interest in India, treated Muslims in the region as culturally different from the Hindu majority of India.

Muslim nationalism even presented the Muslims of India as a general ethnic community within which there were different ethnic and sectarian groups/ Muslim subsectarians. Therefore, most Hindu began to be seen by AIML as an ethnic, cultural and political ‘other’.

Muslim nationalism encapsulated ethnically diverse Muslims of India as all cultural, but one with different ethnic, sectarian and sub -sectarium groups. Therefore, AIML’s purpose was to create a Muslim majority country with Muslim nationalism in its nucleus. If the AIML has led an ‘Islamic’ movement, it would have fought to address and regulate multiple interpretations of Islamic theology held by different sets of Islamic and subsect sects. In fact, according to the political scientist Muhammad Waseem, the concept of Islam in different ethnic groups among Muslims of India differed too much from each other in several theological points.

This is when the ‘Islamic nationalism’ entered the image. Although a little older than Muslim nationalism, the purpose of Islamic nationalism was to regenerate Muslim societies colonized through a rebirth of a global caliphate and laws of universalized Sharia, but fought to compete with the most regional, specific and “modernist Muslim nationalism.

However, while Muslim nationalism managed to produce a separate country of Muslim majority in southern Asia, could not reach an agreement with the ethnic and sectarian fissures that intensified once the country was created, and the “other” Hindu became a lowercase minority in the new country.

Then, as of 1956, but more intensely from 1973 onwards, an Islamic nationalism was introduced. This allowed the entry to the constitution of several laws and rhetoric derived from a majority interpretation of Islamic theology. From then on, it all began to be called “Islamic”, although the Constitution still contained a large part of the secular laws.

According to political scientist Ahmet T. Kuru, Islamic nationalism is a complex already contradictory idea. It combines religious identity with nationalist aspirations. It is different from secular nationalism, which separates the national identity of religion. Muslim nationalism is somewhere between the two. It also combines religious identity with nationalist identity, but maintains theology in the private sphere, to avoid theological complications between sects and subsects, and to mitigate any possibility of these complications that mutate to give birth to a theocracy.

But after 1973, the Pakistani state saw Islamic nationalism as a more robust tool to handle sectarian/ subsectar and ethnic complexities. The term Muslim nationalism transcended to mean Islamic nationalism and then simply disappeared. The question is: Is Islamic nationalism solved complexities? No. He made them even more complex and, in fact, he began to mutate and gave birth to a theocracy.

Until now, this trend has been mitigated by the State to settle for a volatile variant of ‘theo-democracy’ with an ‘Islamic Constitution’ or, in the case, ‘Islamic’ everything, even when much of this is somewhat less.

Then, for the journalist who anticipates a peace force in Gaza composed of soldiers from several Muslim countries, it is an “Islamic army.” But the truth is that it will be only a Muslim army, unless its central purpose is evangelical and jihadist in intention, which will never be the case.

One has to be extremely careful in how the ‘Islamic’ and ‘Muslim’ words are used in the highly divisively and dangerously polarized world in which we live today.

Posted in Dawn, EOS, October 5, 2025