David Saint-Pierre says he had little information to continue in his effort to hunt the guardian of an 111-year-old artifact of the Empress of Wrecks of Ireland.

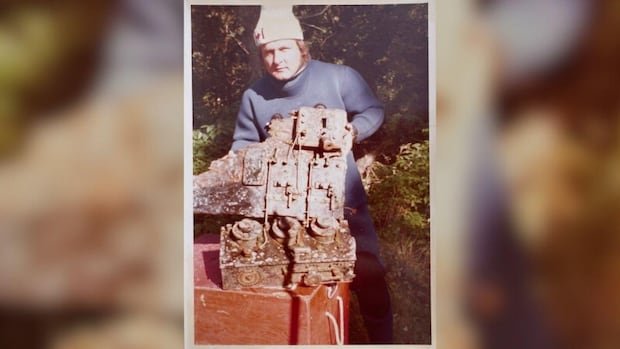

He had a photo of a man in a diving suit, a 1975 direction and a name: Ronald Stopani.

Saint-Pierre-A maritime historian who has studied artifacts recovered from the 1914 shipwreck on the coast of Rimouski, which. -He treated him as a search for modern treasure.

I was looking for Marconi’s wireless device, the communication system used to receive and send wireless telegraphs on the ship before it sinks, claiming the lives of more than 1,000 people. The system included a tuner, a work table and keys to send messages.

Saint-Pierre and the personnel of the Empress Museum of Ireland in Rimouski discovered that it was found and recovered during an expedition to the site 51 years ago by a diving team of Rochester, New York.

With the help of Saint-Pierre, the museum found Stopani, a member of the diving team that first lifted him from the water in the 70s, and in the spring, the device was sent back to Quebec.

‘I didn’t even know if that man was still alive.’

The process of finding Stopani involved dozens of emails, Facebook messages, a handful of phone calls and physical letters, says Saint-Pierre.

“I didn’t even know if that man was still alive,” said Saint-Pierre. “It was a shot in the dark.”

He says he wrote to “probably anyone” with the last name Stopani on Facebook for a few weeks. “If your name is Stopani, you probably have one of my messages in your garbage box,” Saint-Pierre joked.

A January day, he received a call.

In an interview with CBC News, Stopani said he still had the apparatus stored in a clear storage box in his home in Las Vegas, and was eager to donate it.

“As soon as I opened the letter, I even had a photo of mine there, so I knew exactly what it was,” said Stopani, arrived in Las Vegas.

“I wanted to donate them for a while, but I had no way to contact anyone.”

The 81 -year -old man, who divides his time between his homes in Florida and Nevada, says that Media hoped to be contacted.

Years before, his best friend’s family, Fred Zeller, who had directed diving expeditions to the wreck and that he recently died, he told Stopani that they traveled to the Rimouski Museum to donate artifacts that Zeller found and documents of the years.

The donation included Stopani’s photo with the Marconi and the correspondence between him and Zeller since the mid -1970s, when the couple met to dive the shipwreck.

It was that photo and letter that first inspired the personnel of Saint-Pierre and the museum to find Stopani, and the photographic artifacts.

Five decades later, Stopani still remembers the day he raised the articles of the St. Lawrence river, decades before he was forbidden to recover artifacts.

“Believe me, it was cold,” he said, adding that during the immersion in July he could see small pieces of ice floating in the river.

He remembered inflating his dry suit to float to the surface with a bag that, according to him, weighed about 30 kilograms.

For the next 51 years, the artifact was transferred when he brought him with him in his movements from Rochester to Brampton, Ontario, Florida and finally Las Vegas. Having sent the Marconi a few months ago, he says that sending him back to Quebec made him feel “euphoric.”

Device that will be sent for restoration work

Roxane Julien-friolet, a museologist, says that Marconi arrived at the museum in mid-March and in excellent condition.

“We are surprised and really honored to have this really important object of our collection now,” said Julien-Friolet.

She says it will be sent for restoration work and then will be shown.

Operated by telegraphist Ronald Ferguson, this device was a very useful tool, he says, and part of the reason why some were saved from the shipwreck in 1914 after a SOS message was sent.

Saint-Pierre says that putting the eyes on the device offers historians even more information about what happened on board. In a photo, Saint-Pierre’s friend noticed that the switch on the tuner was off.

“It means that … [Ferguson] I had to leave your post [but] He took the time to turn off the machine, “said Saint-Pierre.

“Which was a standard protocol. So really a professional man.”

Ferguson was one of the 465 wreck survivors and lived until the 1980s, he says.

Since then, Saint-Pierre has connected to Ferguson’s son, who lives in the United Kingdom, and informed him that his father’s instrument was finally found.

“That was also a great time to say [him]”Saint-Pierre said.

“Knowing that it still existed and that it would be in the museum was really emotional to him.”