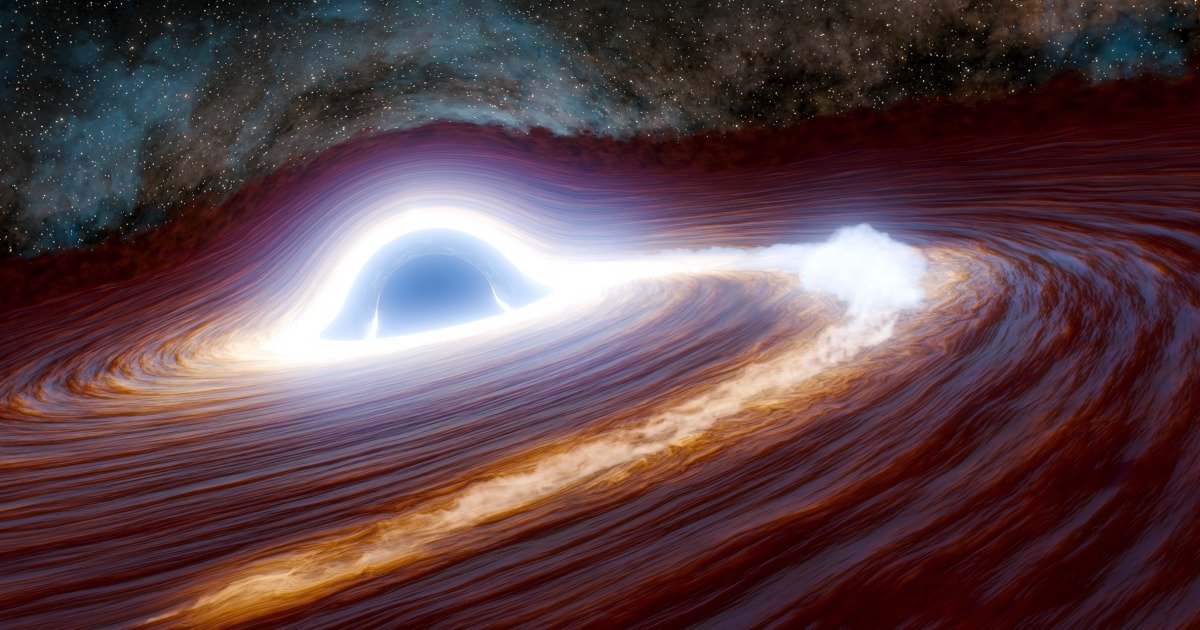

A supermassive black hole violently engulfed a huge star, producing a cosmic explosion with the light of 10 trillion suns, according to a new study.

The black hole flare, as the phenomenon is known, is believed to be the largest and most distant ever recorded: it was detected 10 billion light years away.

“This is really a one-in-a-million object,” said Matthew Graham, research professor of astronomy at the California Institute of Technology and lead author of the study, which was published Tuesday in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Graham said the most likely explanation is the appearance of a black hole, based on the intensity and duration of the explosion, but follow-up studies will help researchers confirm their findings.

It’s not unusual for black holes to consume nearby stars, gas, dust and other forms of matter, but such a gigantic combustion event is extremely rare, Graham said.

“This massive flare is much more energetic than anything we’ve seen before,” he said, adding that at its peak, the explosion was 30 times more luminous than any previous black hole flare seen to date.

Part of the intensity came from the large size of both cosmic objects involved. The unfortunate star that got too close to the black hole is estimated to have at least 30 times the mass of the sun. Meanwhile, the massive black hole and the disk of material surrounding it are estimated to have a mass 500 million times that of the Sun.

The loud bang has been going on for more than seven years, Graham said, and is likely still happening.

The flare was first detected in 2018 during an extensive survey of the sky using three ground-based telescopes. At the time, Graham said, it was recorded as a “particularly bright object,” but during follow-up observations months later, scientists were unable to obtain much useful information.

As such, the black hole flare was largely forgotten until 2023, when Graham and his colleagues decided to revisit intriguing points of interest from their previous study. This time, the astronomers made a rough calculation of the distance to the particularly bright object they had seen, and the result surprised them.

“All of a sudden it was, ‘Oh, this is actually pretty far away,'” Graham said. “And if it’s so far away and so bright, how much energy is being emitted? This is now something unusual and very interesting.”

It’s not yet known exactly how the star came to its demise, but Graham said a case of cosmic bumper cars may have pushed the star out of its regular orbit around the black hole, causing the close encounter.

The findings help provide a more complete picture of how black holes behave and evolve.

“Our idea of supermassive black holes and their environments has really changed in the last five to ten years,” Graham said. “There was this classic picture that most galaxies in the universe have a supermassive black hole in the middle and it just sits there and bubbles and that’s it. Now we know it’s a much more dynamic environment and we’re just beginning to scratch the surface.”

The flare has been steadily fading over time, he said, but will likely remain observable with ground-based telescopes for some years.