Scallop fishermen in the Bay of Fundy keep an eye out for a creamy white species growing on the seafloor that could be described as disgusting.

The invasive marine invertebrate is known as sea vomit, sea squirt, and pancake dough tunicateand large spots were found near Deer Island in 2020 and 2022, according to the Huntsman Marine Science Center in Saint Andrews.

The center approached the Fundy North Fishermen’s Association for help collecting marine vomit samples for a three-year research project.

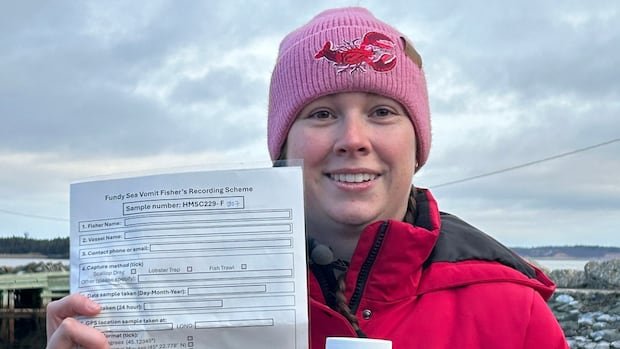

Emily Blacklock, the association’s scientific director, will be among 50 scallop fishermen who will look for sea vomit in their scallop catch, scraping what they find and storing it in vials filled with ethanol.

“They can scrape it off the rocks or the scallops, put it right in the jar and bring it back to shore and then tell us where they found it, how much they found in the area, all the information about the tide and the depth and the weather to help us determine when it was there and why,” Blacklock said.

Scallop season began earlier this month and continues until fishermen reach their quota.

Scallops use large trawls to scrape the seafloor, picking up other things along with the scallops, said Blacklock, who is also a doctoral student at the University of New Brunswick and a part-time lobster fisherman.

About 50 scallop fishermen are helping the Huntsman Marine Science Center in a three-year project by collecting samples of the invasive sea squirt in the Bay of Fundy.

Claire Goodwin, a Huntsman research scientist, leads the research project on marine vomit, native to Japan.

He said the invasive tunicate forms “a rubbery crust” on the ocean floor, disturbing the area’s marine ecosystem.

“It can grow very, very quickly once it’s introduced into a location,” Goodwin said. “It doesn’t have many native predators. There’s nothing really eating it to keep the population down, and it forms very large maps on the surface of the seafloor.”

Goodwin said these patches smother marine life in the area by competing for space with other species that rely on the seafloor or rocks for food and shelter. He said the rubbery bark prevents other organisms from accessing the seafloor and suffocates larvae trying to get out.

He said if these patches are left unchecked, they can extend several meters and eventually cover the entire seabed in an area, which can harm industries such as the scallop fishery.

Goodwin said sea vomit may have started growing in the area years ago, but fishermen didn’t know it.

These invasive species die off during winters when water temperatures drop, but temperatures haven’t dropped much in the Bay of Fundy in recent years because of climate change, he said.

Goodwin said marine vomit can also grow on man-made structures such as docks, boat hulls and fishing equipment such as scallop trawls.

“It is very important to stop the spread of this species in the Bay of Fundy because it can have significant impacts,” he said. “And really, if we can stop its spread, we don’t have to worry about trying to eradicate it once it’s present in a place.”

The Department of Fisheries and Oceans-funded project will cost about $750,000.

Goodwin said the goal is to determine the spread and impact of marine vomit in the Bay of Fundy and find possible solutions to contain it.

Sample collection and studies will continue for three years in different areas, with the help of fishermen, divers and remotely operated underwater vehicles, he said.

“And we will do the genetic work that will be done primarily in the last two years of the project once we have started getting the samples, looking at the genetics of the population and determining where it comes from.”

The genetic studies will be done in collaboration with the University of New Brunswick, he said.

Goodwin said his team will also conduct environmental DNA studies each year to identify areas of the bay where the species might be present.

When the locations of marine vomit in the Bay of Fundy are mapped, the team will develop an educational display for New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, he said.

Blacklock said each angler receives an identification guide, four vials to collect samples and a form to record coordinates and weather conditions.

He said that although 50 scallop fishermen are already participating, other interested parties are welcome. Sea vomit may not be present in all fishing areas.

“We don’t really know because we don’t know the distribution. Some [fishers] “I may have vials and never see him all season.”