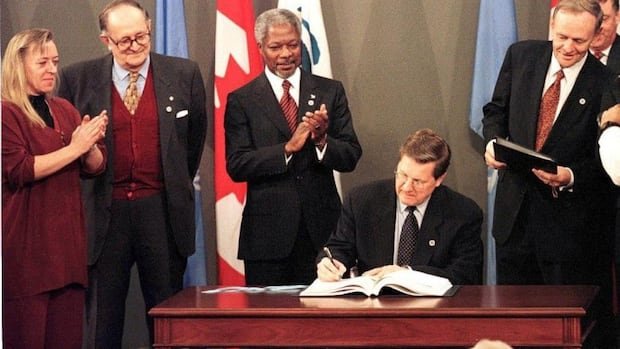

Paul Hannon remembers having been in Ottawa in 1997 when representatives from all over the world arrived in the city to sign an agreement that prohibits the production and use of land mines.

At that time, Hannon was a volunteer for Mines Action Canada, a coalition of groups that advocate the use of mines in armed conflicts.

“It was a quite magical moment in December, the first week of December 1997, when 122 countries around the world came here to sign the treaty,” he told CBC News.

But 28 years later, the agreement is being challenged.

Ukraine and five other countries, some of which are NATO members, have moved to withdraw from the Convention or have indicated that they would, citing increasing military threats from Russia.

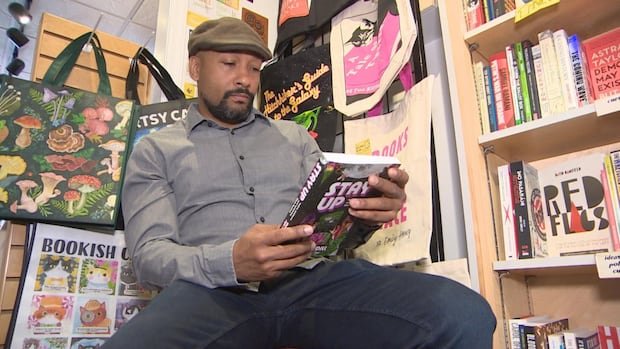

Hannon and others who pressed for the treaty are regretting how it is getting rid. They also argue that Canada, the country that negotiated it, should play a more active role to prevent countries from retiring.

“Once they have gone through that process and have gone, then people will begin to think:” Where are those countries that asked for this treaty, where were the countries that were the great leaders? “Hannon said.

‘We were where land mines were prohibited’

Lloyd Axworthy, who served as Foreign Minister from 1996 to 2000, was the driving force behind the treaty in 1997.

He said that the inspiration for the initiative occurred after he and his 11 -year -old son visited an exhibition about land mines.

“He said: ‘Well, aren’t you the Foreign Minister, Dad?’ I said: ‘Yes.’ He said: “Why can’t you do something about it?”

The way in which Axworthy managed to forge the treaty, by including civic groups that were generally not included in such agreements, would also be known as the “Ottawa process.”

Alex Neve, a human rights lawyer and former general secretary of Amnesty International of Canada, said the treaty, and Ottawa by association, became widely known in international circles.

“The degree to which other states have regularly call it the Treaty of Ottawa or the Ottawa convention, you listen to both, it is a real sign that the rest of the world also recognizes the leadership of Canada,” said Neve.

‘We are no longer playing that role’

Last month, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy signed a decree on the withdrawal of the Convention, although he still needs parliamentary approval to enter into force.

The country’s foreign ministry said that the use of antipersonal mines of Russia “has created an asymmetric advantage for the aggressor.”

Neve said the movement establishes a preceding evil.

“Every time a nation shows the rest of the world that can go back from its international obligations, it can withdraw from its international obligations, it runs the risk of encouraging other governments to do the same,” he said.

Neve and Axworthy also said that Canada should commit more to countries to ensure that they remain signed in the Convention.

“We were one of the leaders in no armament proliferation,” Axworthy said. “And we are no longer playing that role.”

For Hannon, the collapse of the treaty is also itch at the local level, since it is something that everyone in Ottawa, and Canada, should be proud.

“Everyone thinks that the world knows about us due to hockey or Wayne Gretzky. And now I would say that most of the world knows us because we were where the terrestrial mines were prohibited. That was really significant,” he said.

“I would certainly like people to remember [the treaty] Much more than this is the city where the convoy took over … for two weeks. I think it is a much better memory to have and a much better claim to fame. “