Although Alberta’s oil platform continues to earn billions of dollars in earnings, much of that money is reaching the shareholders’ pockets instead of the large expansions of their operations.

At the time of the last boom, oil producers poured a large part of their profits again in capital spending. In 2014, for example, investment in oil and gas in Canada ranged around $ 80 billion.

Today, it is closer to $ 30 billion, according to the Last numbers of Arc Energy Research Institute, which models the entire Western Canadian sedimentary basin.

It means that in recent years, an avalanche of cash has not caused a wave of new projects in the province. The Fort Hills Mine of Suncor, the last important installation of oil tankers, opened in 2018.

“The real change in behavior was really more before 2020, where companies were putting much more of their cash flow in [capital expenditures] and growth, “said Jackie Forrest, executive director of ARC.

“After the 2020 period, he really changed to today. He only goes to half the cash flow towards [capital expenditures] and growth. The other half goes to shareholders.

“Governments are also a very significant interested part that receives almost as much as shareholders. Of course, that benefits all Canadians through royalties and taxes.”

The previous graph shows the cash flow after taxes, which is the money that oil companies have left after covering their costs, even governments.

They use it to pay the debt, invest in projects, buy other assets or return money to shareholders through dividends and repurchases of shares, said Richard Masson, executive member of the Faculty of Public Policies of the University of Calgary and the former CEO of the Alberta oil marketing commission.

Masson said that companies are reinvirting approximately half of their cash flow after taxes, which is a higher proportion than during the first years of pandemic.

But most of that money is destined to maintain current production, not expand it, he said.

“There are only small amounts of that that are actually growth capital,” he said.

“It’s not bad,” he added, “but we have not been able to grow the industry because we have not been insurance for market access and good prices.”

What is at stake?

Charles St-Arnaud, chief economist of Alberta Central, the Central Banking Center of Credit Cooperatives in the province, said that the data available for non-Canadian oil producers show similar patterns.

“They are also reinvirting less of their income in their operation,” he said.

St-Arnaud said that there are many international factors at stake here, one of them are forecasts, such as the International Energy Agency, which shows that oil demand is poured somewhere in the 2030s and then gradually decreases.

“Does it make sense worldwide to invest massively in the expansion of oil production in this context?” said.

Meanwhile, Masson said that future investment depends on a series of factors.

“It depends completely on resource and access to the market, and access to capital and the skill of the workforce,” he said.

“Canada is one of the most competitive places in the world for investment, and we have a lot of running room.

“Even in a world that sees oil peak in the mid -2030s, because even then, almost all real forecasts, which are different from the scenarios, most forecasts see a very shallow decrease after 2050.”

At the same time, worldwide expectations of investors have changed, said Masson.

“That arose from the Permian [Basin] In TexasWhere it was growing so fast, so much investment was happening that shareholders continued to add more funds to the industry, but they did not get any performance, “he said.

“Eventually, they sank and said we need to see more effective returning. And that trend also extended through New York throughout Canada, where Canadian companies had to compete by returning cash to shareholders.”

Masson said that industry leaders also continue to quote regulatory uncertainty, even when it comes to legislation such as bill C-69, also known as the impact assessment law, and the proposed emissions limit, as barriers that have a new investment.

Stable, but not busy

In Fort McMurray, Alta., The heart of Alberta’s oil sands, the volatile nature of the boom and fall of the province has been testified first -hand for decades.

These days, it seems that things are not boom or busts.

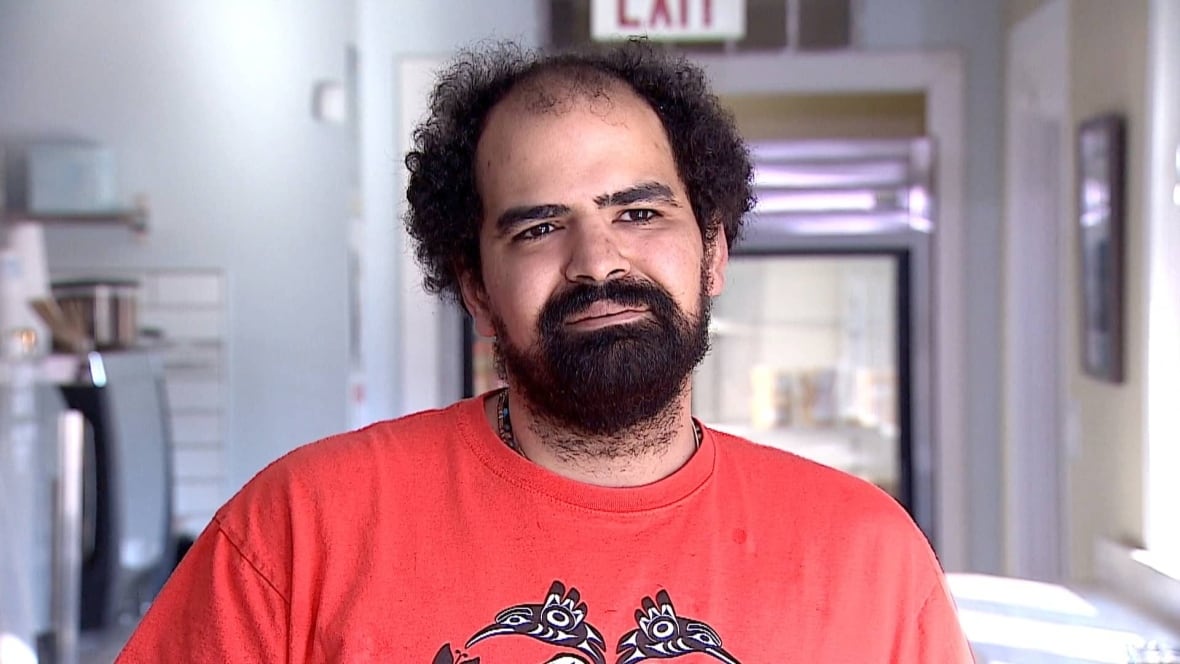

For Owen Erskine, owner of Mitchell’s Cafe in the center of Fort McMurray, in recent years they have been stable, but not occupied.

“I don’t think we have seen a great boom of staff as in past years … We are seeing more oil at some points, but I think they are a little bottleneck where it is investment and that kind of thing,” said Erskine.

“We are not seeing a great huge [rush of] People outside the city who comes to the city at this time. “

Erskine, who has lived in Fort McMurray in 36 years, said the community is well known to the nature of the industry.

“What we are seeing now is, as, since the last two busts, we don’t have such an intense boom,” he said. “The busts have become a little less amazing, especially as a small business like us.”

THE PHASE ‘MATURA’

Oil has been a blessing for the province, but it also means that Alberta depends largely on a income flow that will face challenges as the energy transition continues, according to ST-Anaud.

“[The government has] I have been very proactive to ensure that this income is still there and protects that income, because it is a great source of financing for the government, “he said.

“If it is not there, there will be a very difficult decision. And a very hard conversation is, do we maintain the level of services or do we increase taxes?”

In St-Arnaud’s opinion, the industry may have reached a “mature phase” where companies focus on optimizing existing operations instead of expanding production.

“As much as I said that in the mid -2000s in mid -2010 it was the starting phase, well, we are in a mature phase where we are producing,” he said. “These companies are making a very good return of these investments, and they do not see the need to expand drastically.”

Meanwhile, Masson said that the recent expansion of Trans Mountain Tpeline has helped, but it is Already close to total capacity. The construction of a new infrastructure, especially pipes to the west coast, could take up to a decade, which hinders long -term planning.

“It will probably continue in that range, from $ 30 to $ 40 billion, for the future, until we know what we have for access to the market and we see some of the federal policies that CEOs are talking about changing,” he said.

Next year I could also try how oil companies prioritize their money if prices fall, said Forrest.

“If we get prices in the following $ 60 [US] or at $ 60 [US] Rank, I think you’re going to start understanding what priority is, “he said.

“And I think that shareholders will be a fairly large priority in terms of, if the cash flow is more scarce, what they do with it.”