North Carolina Gov. Roy Cooper, on his last day in office Tuesday, commuted the death sentences of 15 inmates to life in prison without parole.

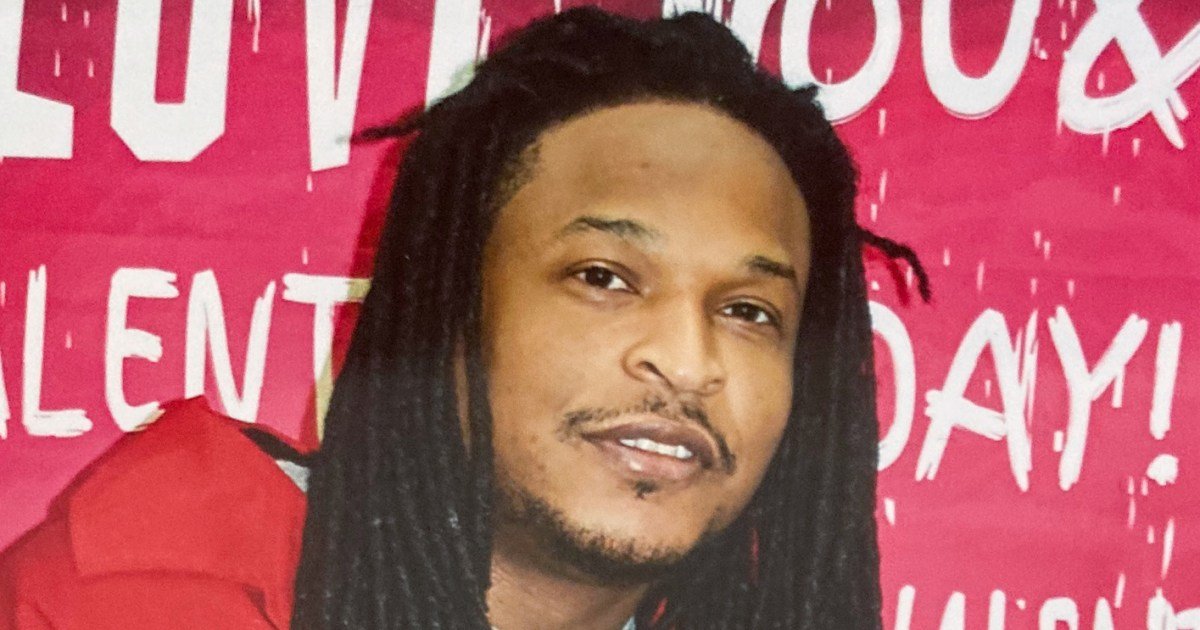

One of the inmates granted clemency was convicted murderer Hasson Bacote, a black man who had challenged his sentence under the Racial Justice Act of 2009, a groundbreaking state law that allows convicted inmates to request a resentencing if they can. demonstrate that racial prejudice played a role in their cases.

The pardons came as Superior Court Judge Wayland Sermons Jr. was considering the case of Bacote, who was sentenced to death in 2009 by 10 white and two black jurors.

“These reviews are among the most difficult decisions a governor can make and the death penalty is the harshest sentence the state can impose,” Cooper said in a statement. “After extensive review, reflection and prayer, I have concluded that the death sentences imposed on these 15 individuals should be commuted, while ensuring that they will spend the rest of their lives in prison.”

While Cooper insisted that “no factor was determinative in the decision of any case,” among the factors considered were “the possible influence of race, such as the race of the defendant and the victim, the composition of the jury, and the final jury “. “

Opponents of the death penalty had been urging Cooper to commute the sentences of the 136 prisoners currently on death row in North Carolina. While the Democratic governor fell short of that figure, the state has not executed any prisoners since 2006.

Cooper’s action was applauded by the American Civil Liberties Union, the Legal Defense Fund, the Center for Death Penalty Litigation and others working to repeal the death penalty.

“This decision is a historic step toward ending the death penalty in North Carolina,” Cassandra Stubbs, director of the ACLU Capital Punishment Project, said in a statement.

The other inmates whose sentences were commuted are:

Iziah Barden, 67, convicted in Sampson County in 1999; Nathan Bowie, 53, convicted in Catawba County in 1993; Rayford Burke, 66, convicted in Iredell County in 1993; Elrico Fowler, 49, convicted in Mecklenburg County in 1997; Cerron Hooks, 46, convicted in Forsyth County in 2000; Guy LeGrande, 65, convicted in Stanly County in 1996; James Little, 38, convicted in Forsyth County in 2008; Robbie Locklear, 52, convicted in Robeson County in 1996; Lawrence Peterson, 55, convicted in Richmond County in 1996; William Robinson, 41, convicted in Stanly County in 2011; Christopher Roseboro, 60, convicted in Gaston County in 1997; Darrell Strickland, 66, convicted in Union County in 1995; Timothy White, 47, convicted in Forsyth County in 2000; Vincent Wooten, 52, convicted in Pitt County in 1994.

Sermons began reviewing the Bacote case in February, after the ACLU and other groups filed a challenge on behalf of the Johnston County convict.

Bacote, now 38, is being held in a Raleigh prison while death sentences in North Carolina remain on hold, in part because of legal disputes and difficulties obtaining lethal injection drugs.

The law Bacote used to challenge his sentence was passed in 2009. But in 2013, then-Gov. Pat McCrory, a Republican, repealed the law, arguing that it “created a judicial loophole to avoid the death penalty and not a path to justice.”

But in 2020, the state Supreme Court ruled in favor of many of the inmates, allowing those, like Bacote, who had already filed challenges in their cases, to move forward.

At the time, nearly all people on death row, including black and white inmates, requested reviews under the Racial Justice Act, according to The Associated Press.

During Bacote’s two-week trial court hearing, several historians, social scientists, statisticians and others testified that the jury selection process in Johnston County, a majority-white suburban area near Raleigh that exhibited prominently billboards for the Ku Klux Klan during the Jim Crow era, had long been infected by racism.

In court papers, Bacote’s attorneys suggested that local prosecutors at the time of his trial were “nearly twice as likely to exclude people of color from jury service as white people.” In Bacote’s case, prosecutors chose to exclude potential black jurors. The number of jurors is more than three times that of white potential jurors, lawyers argued.

Bacote’s legal team also provided evidence indicating that in Johnston County, the death penalty was 1.5 times more likely to be sought and imposed on a black defendant and twice as likely “in cases with black defendants minorities.”

Then-North Carolina Attorney General Josh Stein’s office had sought to delay Bacote’s hearing. They argued in a court filing that the claims made by Bacote’s attorneys were based, in part, on a Michigan State University study that the North Carolina Supreme Court had already deemed “unreliable and fatally flawed” last year. ”.

While the attorney general’s office said in its court filing that racial bias in jury selection is “abhorrent,” the office added that “a claim of racial discrimination cannot be presumed based on a defendant’s mere assertion.” “You have to try it.”

Stein, a Democrat, is now governor-elect of North Carolina.