In January, an old position on Elon Musk’s social networks, X, became a concern for the police in the Indian city of Satara. Written in 2023, the brief message of an account with a few hundred followers described a high -level politician as “useless.”

“It is likely that this publication and content will create a serious community tension,” wrote Inspector Jitendra Shahane in a content recovery notice marked as “confidential” and aimed at X.

The post, which remains online, is among the hundreds cited by X in a lawsuit filed in March against the government of India, challenging a radical repression in the content of social networks by the administration of Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

Since 2023, India has increased efforts to monitor the Internet by allowing many more officials to present the elimination orders and send them directly to technology companies through a government website launched in October.

X argues that India’s actions are illegal and unconstitutional, and that they soak freedom of expression by empowering dozens of government agencies and thousands of police officers to suppress the legitimate criticisms of public officials.

India maintains in judicial documents that its approach addresses a proliferation of illegal content and guarantees online responsibility. He says that many technological companies, including the Google of Meta and Alphabet, support their actions. Both companies declined to comment for this story.

Musk, who calls himself an absolutist of freedom of expression, has faced the authorities in the United States, Brazil, Australia and elsewhere on compliance and demolition demands.

But as regulators weigh worldwide the protections of freedom of expression against concerns about harmful content, Musk’s case against Modi’s government in the Superior Court of Karnataka is directed to the entire basis for hardened internet censorship in India, one of the largest users of X users.

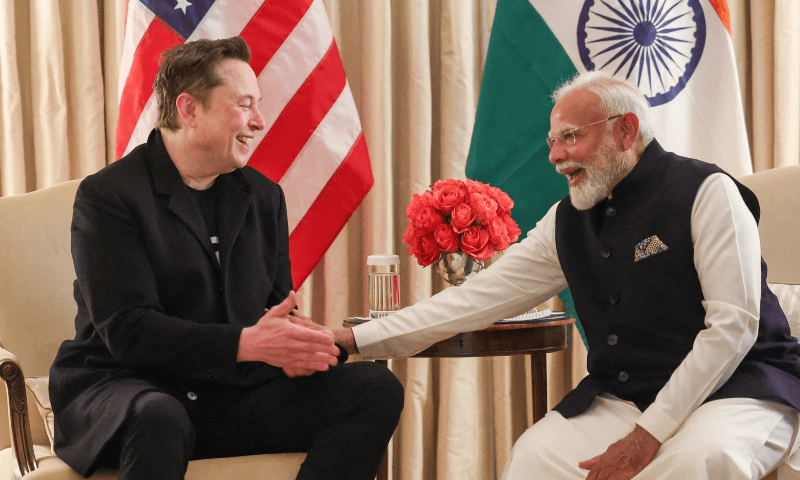

Musk said in 2023 that the nation of southern Asia had “more promise than any large country in the world” and that Modi had pushed him to invest there.

This account of the battle behind the scene between the richest person and authorities in the world in the world’s most populated country is based on a Reuters Review of 2,500 pages of non -public legal presentations and interviews with seven police officers involved in content recovery requests.

It reveals the operation of a demolition system wrapped in secret, the anger of some Indian officials on “illegal” material in X and the broad spectrum of content that the police and other agencies have tried to censor.

Although demolition orders include many that sought to counteract erroneous information, they also cover the directives of the Modi administration to eliminate news about a deadly stampede, and the state police demands to scrub the cartoons that represented the prime minister with an unfavorable light or made fun of local politicians, the presentations show.

X did not respond to Reuters’ Questions about the case, while the Ti Ministry of India declined to comment because the matter was before the court. Modi’s office and his ministry of origin did not answer the questions.

There have been no immediate signs of bitter personal relationships between Musk and Modi, which have enjoyed a warm public relationship. But the confrontation occurs when the entrepreneur born in South Africa, whose commercial empire includes the manufacturer of EV Tesla and Starlink Starlink, the satellite Internet provider, prepares to expand both companies in India.

Even the supporters of the Bharatiya Janata (BJP) party of Mod

Koustav Bagchi, lawyer and member of BJP, published an image in X in March that represented a rival, the Prime Minister of Western Bengal, Mamata Banerjee, in an astronaut demand. The State Police issued a demolition notice, citing “risks to public security and national security.”

Bagchi told him Reuters The publication, which is still online, was “cheerful” and was not aware of the demolition order. The office of the Prime Minister and the State Police did not respond to Reuters’ Consultations.

From the first position of 2023, said Shahane, Satara’s police officer, said Reuters He could not remember the demolition order, but said that the police sometimes ask the platforms that block the offensive viral content proactively.

‘Censorship Portal’

For years, only IT and broadcasting ministries of India could order the elimination of content, and only for threats to sovereignty, defense, security, foreign relations, public order or incitement. Some 99 officials from all over India could recommend demolition, but the ministries had the last word.

Although this mechanism remains in place, Modi’s Ministry in 2023 trained all federal and state agencies and police officers to issue demolition notices for “any information that is prohibited by any law.” They could do so under the existing legal provisions, the ministry said in a directive, citing the need for “effective” content.

The companies that do not comply can lose immunity for the user’s content, making them responsible for the same sanctions that a user could face, which could vary greatly depending on the specific material published.

The Modi government took a step further in October 2024. He launched a website called Sahyog, Hindi for collaboration, to “facilitate” the issuance of demolition notices, and asked Indian officials and social media signatures that are uploaded on board, show the memoranda in the judicial documents.

X did not join Sahyog, who has called a “censorship portal,” and demanded the government earlier this year, challenging the legal basis for both the new website and for directive 2023 of the Ministry of IT.

In a presentation of June 24, X said that some of the blocking orders issued by the officials “are directed to the content of the satire or the criticisms of the ruling government, and show a pattern of abuse of authority to suppress freedom of expression.”

Some defenders of freedom of expression have criticized the most strict demolition regime of the government, saying that it is designed to suffocate dissent.

“Can it be affirmed that some content is illegal to be called illegal simply because the government affirms that?” Subramaniam Vincent, director of journalism and media ethics at the Markkula Center for applied ethics of the University of Santa Clara.

“The Executive Branch cannot be so much the arbitrator of the legality of the media content and the emitter of demolition notices.”

Red dinosaur

Judicial presentations reviewed by Reuters Federal and state agencies ordered X to eliminate around 1,400 positions or accounts between March 2024 and June 2025.

More than 70 percent of these elimination notices were issued by the Indian Cybercrime Coordination Center, which developed the Sahyog website.

The agency is within the Ministry of Interior, which is headed by the assistant of Modi Amit Shah, a powerful figure in the BJP ruler.

To counteract X in the Court, the Government of India presented a 92 -page report written by the Cyber Crime Unit to show that X is “hosting illegal content.” The unit analyzed almost 300 publications that it considered illegal, including erroneous information, deceptions and child sexual abuse material.

X serves as a vehicle to “disseminate hatred and division” that threatens social harmony, while the “false news” on the platform have caused unpalified law and order problems, the agency said in the report.

The government’s response to the demand of X highlighted examples of misinformation.

In January, the cyber crimes unit asked X to eliminate three positions that contained what officials said they were manufactured images that portrayed Shah’s son, the international president of the Cricket Council, Jay Shah, “in a derogatory way” next to a woman dressed as a bikini.

The publications “Outstanding Office Beores and VIP” dishonors “, said the notices.

Two of those publications remain online. Jay Shah did not respond to Reuters Consultations.

Other directives went beyond aiming fake news. X

These included February directives seeking the elimination of publications from some media, including two Adani Group’s NDTVwhich contained Stampede news coverage at the largest train station in New Delhi that left 18 dead.

He NDTV Publications are still online. NDTV did not respond to Reuters The consultations and the Railroad Ministry declined to comment.

In April, the police in Chennai asked X to eliminate many “deeply” and “provocative” publications, including a cartoon now inaccessible with a red dinosaur labeled as “inflation”, which portrayed Modi and the Prime Minister of the State of Tamil Nadu as well as fighting to control prices.

The same month, the police demanded the elimination of another cartoon that mocked the lack of preparation of the state government for floods by showing a boat with holes.

X told the judge that the cartoon was published in November, and could not “encourage political tensions” several months later, as the Chennai police said. The publication remains online.

The state government did not respond to a request for comments.

When Reuters He visited the Chennai cybercrime police station that issued these directives, Deputy Commissioner B. Geetha criticized X for rarely acting on demolition requests.

X does not “completely understand cultural sensibilities,” he said. “What can be acceptable in some countries can be considered taboo in India.”