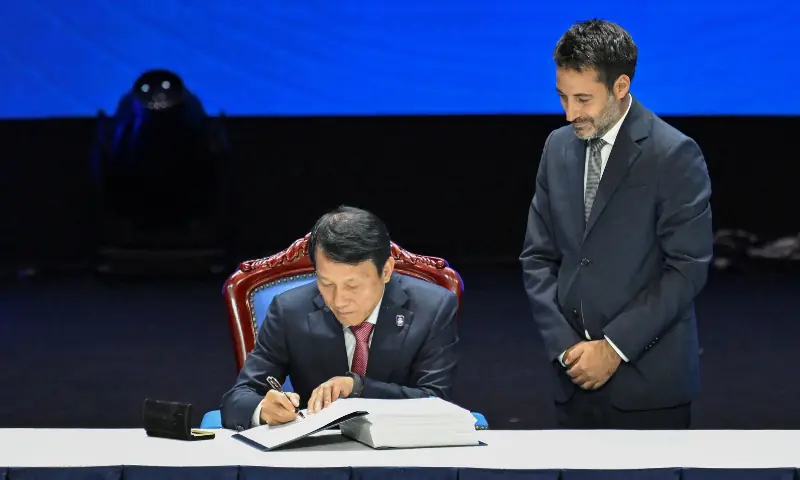

The countries signed their first United Nations (UN) treaty against cybercrime in Hanoi on Saturday, despite opposition from an unlikely group of technology companies and human rights groups who warn of greater state surveillance.

The new global legal framework aims to strengthen international cooperation to combat digital crimes, from child pornography to transnational cyber scams and money laundering.

More than 60 countries signed the declaration on Saturday, meaning it will come into force once it is ratified by those states.

UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres described the signing as an “important milestone” but that it was “just the beginning.”

“Every day, sophisticated scams destroy families, steal immigrants and drain billions of dollars from our economy… We need a strong, connected global response,” he said at the opening ceremony in Vietnam’s capital on Saturday.

The United Nations Convention against Cybercrime was first proposed by Russian diplomats in 2017 and approved by consensus last year after lengthy negotiations.

Critics say its broad language could lead to abuses of power and allow cross-border repression of government critics.

“Multiple concerns were raised during the negotiation of the treaty about how it ends up forcing companies to share data,” said Sabhanaz Rashid Diya, founder of the Tech Global Institute think tank.

“It’s almost an approval of a very problematic practice that has been used against journalists and in authoritarian countries,” he said. AFP.

‘Weak’ safeguards

Vietnam’s government said this week that 60 countries were registered for the official signing, without revealing which ones.

But the list is probably not limited to Russia, China and their allies.

“Cybercrime is a real problem around the world,” Diya said. “I think everyone is dealing with that.”

The wide-ranging online scam industry, for example, has exploded in Southeast Asia in recent years, with thousands of scammers involved and victims scammed around the world out of billions of dollars a year.

“Even the most democratic states, I think, need some degree of access to data that they don’t get with existing mechanisms,” Diya said. AFP.

Democratic countries could describe the UN convention as a “compromise document” as it contains some human rights provisions, he added.

But these safeguards were called “weak” in a letter signed by more than a dozen human rights groups and other organizations.

technology sector

Big tech companies have also expressed concern.

The Cybersecurity Tech Accord delegation to the treaty talks, representing more than 160 companies including India’s Meta, Dell and Infosys, will not be present in Hanoi, its boss Nick Ashton-Hart said.

Among other objections, those companies previously warned that the convention could criminalize cybersecurity researchers and “allows states to cooperate in almost any criminal act they choose.”

Potential overreach by authorities poses “serious risks to corporate IT systems that billions of people rely on every day,” they said during the negotiation process.

In contrast, an existing international agreement, the Budapest Convention on Cybercrime, includes guidance on using it in a “rights-respecting” way, Ashton-Hart said.

The location of the signing has also drawn attention, given Vietnam’s history of cracking down on dissent.

“Vietnamese authorities routinely use laws to censor and silence any online expression of opinions critical of the country’s political leadership,” said Deborah Brown of Human Rights Watch.

“Russia has been a driving force behind this treaty and will no doubt be pleased once it is signed,” he said. AFP.

“But a significant amount of global cybercrime comes from Russia, and it has never needed a treaty to address it from within its borders,” Brown added.

“This treaty cannot compensate for Russia’s lack of political will in that regard.”