Texas’s teenager Walter Campbell was not sure what to do with pointed pieces that make fun of the Prairie land during a fossil search last month with his grandfather in southern Manitoba.

But in a few moments it was clear to the hugged experts around the couple in the secret excavation site that Campbell, 14, had unearthed teeth and jawbone of a Mosasaur, a reptilian predator with legs of the wing that hunted seas inland 80 million years ago.

“About six inches or so, I hit bone,” Campbell said. “I called the boy and he says: ‘What is this? I think it could be a skull of Mosasaur’, and I was very surprised.”

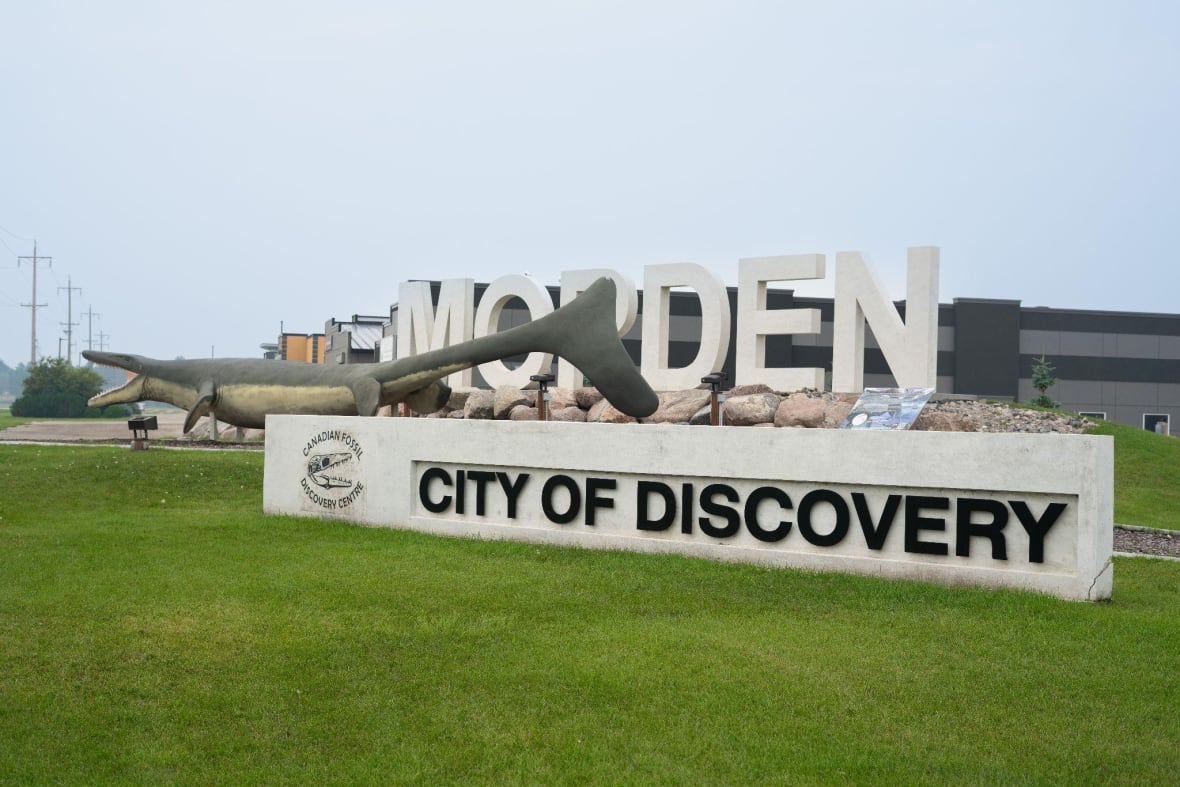

It is the third set of Mosasaur remains that are in just three field seasons in this new site of the Discovery Fossil Canadian Fossil center, where paleontologists and fossil hunters provide guided summer excavations to the public.

“It is probably like what happened in your life,” said Walter’s mother, Angela Campbell, in a recent interview with CBC News. “Yes. Well, as, apart from my birth,” he replied.

Walter and his expatriate parents were in the city of Lorena, just south of Waco, Texas, visiting his grandfather Dave Stobbe in June.

Stobbe bought a couple of excavation passes through the fossil center. Walter is curious about nature and science, and Stobbe thought he could want to take his father or mother.

“And he chose me, and I have to confess that I had a slightly bad attitude, because here we are outdoors, on their knees, digging on earth, the warm climate,” said Stobbe, 73, looking at the active excavation site this week.

“But he wanted me to come, and I’ll tell you that it was an incredible day.”

Look | Teen Teen Bavia Mosasaur of 80 million years in Manitoba:

Walter Campbell, 14, has the rights to blush unlike almost any other teenager. He has just returned home in Texas from a visit to see his grandfather in Manitoba, where he unearthed the bones of the skull of a Mosasaur of 80 million years that he has been called from him.

In the weeks after that day, subsequent excavations have discovered the bones of the limbs, vertebrae, hips and skulls, said Gerry Peters, laboratory and field technician with the fossil center in Morden, about 100 kilometers to the southwest of Winnipeg.

Peters has had the fossil hunting error since he was eight years old in the 1970s, when he found his first Mosasour bone.

Part of your work is to explore probable bone beds. He does it by scanning the environment in search of clues. But it can be more an art than science, admits.

“I can’t explain it … I guess you develop a special ability,” Peters said.

That ability guided him where he directed Walter and his grandfather to dig.

“Everyone really got excited, like you,” Peters said. “I love seeing children when they find a fossil and take it out of the ground, you can see that their eyes light up.”

Bruno Costa saw the light in Walter’s eyes that day.

Costa is a doctoral student in the Department of Earth Sciences of the University of Manitoba who studies Paleontology and Geochemistry.

He is trying to decipher the analysis of rocks and fossils what life was like for the many marine dinosaurs, birds, sharks, fish, turtles and other creatures of former local ecosystems, even along Manitoba’s escarpa.

That crest of hills and slopes, which extend through western Manitoba to the border of Saskatchewan, are what remains of the western coasts of the AGASSIZ prehistoric lake.

But the Mosasaurs wandered in the late Cretaceous, long before that giant glacial lake was formed 11,500 years ago and exhausted Hudson Bay about 3,800 years later.

Local fossils of the late cretaceous rest under 13 layers of sediment and bentonite, a clay that was formed by decomposing volcanic ashes.

“Manitoba would be completely underwater at this time, 80 million years ago,” Costa said.

“It was a quite lush atmosphere for these animals, so it basically imagines a complete ocean of probably more than 300 feet deep at this time …

That’s how it is. Walter now has blush rights unlike almost any teenager.

“Always … we informally inform each specimen and obviously this will be Walt, our new Mosasaur,” said Adolfo Cuetara, curator of the Fossil Discovery Center.

It is a nickname that Walter says that his grandfather released the fossil team at the time of discovery.

“It was a bit spontaneous but it was very exciting,” Walter said. “Now I have evidence for all people in school that I unearthed this Mosasaur because it is named after me.”

Cuetara said that more evidence is needed to discover exactly what species Walt is from three local varieties in Mosasaur. What is clear is that Walt is not the most gigantic type that the Discovery center has long promoted as a pet.

Bruce The Mosasaur, a Tylosaurio more than 13 meters long dug west of Morden in 1974, and the head of Guinness World for the major Mosasaur on public exhibition, could have been almost twice the length of Walt.

Stobbe and his grandson do not care if Walt does not rival Bruce’s record.

Fossil excavations cost around $ 200 per person, but it was an invaluable experience for the grandfather-niet duo.

“There are so many things that you can spend money with your grandchildren. Go to a Winnipeg Jets game. Or go to Disney World and set up walks. But in my backyard I have paleontologists that give a grandfather already a grandfather a practical experience. That was quite special.”