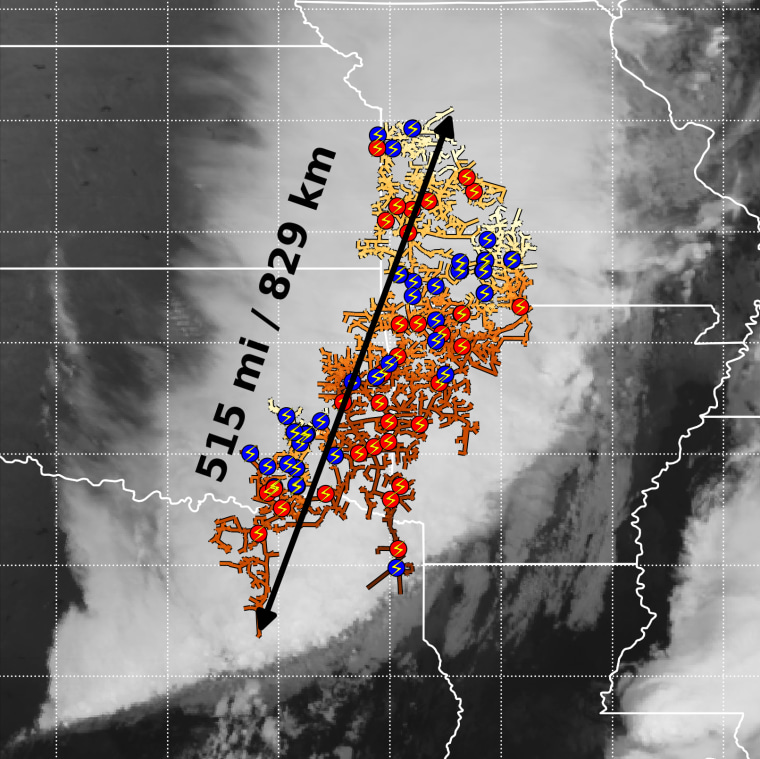

A huge flash of ray of 515 miles that crossed at least three states has been named the longest in the registered history of the world.

The “megaflash” of 2017 extended from East Texas to near Kansas City, a distance that would take at least eight hours by car or 90 minutes by commercial plane, according to the World Meteorological Organization. In comparison, the average ray generally measures less than 10 miles, according to the National Meteorological Service.

The OMM, an agency within the United Nations, announced Thursday that it certified the megaflash as the lighter lightning in the registry. He hit on October 22, 2017, during a severe storm that hit much of the great plains.

A megaflash is a giant ray that travels huge distances from its point of origin, Randall Cerveny said, a professor of geographical sciences at the Arizona State University and member of the OMM committee confirmed by the new record.

“It’s an incredibly strange phenomenon,” he said. “We only discovered them 10 years ago, when we could use a particular set of technologies to detect the start and completion locations of the lights of lightning.”

Megaflashas are not entirely rare, but generally only occur in parts of the world where specific geographical and atmospheric conditions can produce the most severe thunderstorms, said Cerveny. In the big plains and in the west, for example, the warm and humid air of the Gulf of Mexico clashes with the driest and coldest air in the north, creating a strong atmospheric instability.

When these conditions mix and produce severe storms, megaflashas of rays can occur. According to Cerveny, these extra long ray bolts in the United States, Argentina and southern France, and scientists think they can also occur in parts of China and Australia, according to Cerveny.

The 2017 megaflash was produced by an immense storm that covered a large strip from the United States, from Texas to Iowa and Missouri. Although megaflashas can be extended through multiple states, they form in the atmosphere and, therefore, rarely cause damage to the ground, Cerveny said.

“They have more than 10,000 to 18,000 feet high, in the layers above average of a thunderstorm,” he said.

The ray of 515 miles long was described in a study published Thursday in the American Meteorological Society Bulletin.

“These new findings highlight important public security concerns about electrified clouds that can produce flashes that travel extremely large distances and have a great impact on the aviation sector and can cause forest fires,” said the general secretary of the OMM Celeste Saulo in a accompanying statement.

The extreme conditions that generate them are a reminder of whose powerful and dangerous can be ray storms. In the United States, Lightning kills approximately 20 people each year and hurts more, according to the weather service.

With the classification on Thursday, the 2017 Lightning Flash now exceeds the previous world record established five years ago in approximately 38 miles, according to the OMM. That Bolt of Lightning broke out on April 29, 2020 and covered 477.2 miles through parts of the southern US.

The 2017 megaflash was identified after scientists reexamined the file measurements taken when the storm occurred.

“When the original studies were conducted, we did not have the technology we have today,” said Cerveny. “Now we have this instrument in a meteorological satellite that precisely detects lightning and can identify with precision where, how long and a lightning event takes place.”

Experts said that they are likely to be even longer megaflashas in the coming years, particularly as satellite technologies improve the ability to detect them.

“Over time, as the data registration continues to expand, we can even observe the rarest types of extreme lightning on Earth and investigate the broad impacts of the rays in society,” he said in a statement by the main author of the study, an atmospheric scientist at the Center for Severe Storm Research in the Georgia Institute of Technology, in a statement.

The OMM Meteorology and Climate Committee maintains official records of global, hemispheric and regional ends, even for temperature, rain, wind, hail, rays, tornadoes and tropical cyclones.