There are actually two solid foods that eight-year-old Mohammad Farhad eats safely: hard-boiled eggs, because of their taste, and spaghetti or lasagna, because of their shape.

Mohammad, explains mother Ramzia El Annan, has avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder, known as ARFID.

While it is an eating disorder, it differs from anorexia or bulimia because it is not driven by concerns about weight or body image. Rather, it is a severe, sometimes debilitating, sensory reaction to many or most types of foods.

El Annan says he wants to share his family’s story because the disorder is often misunderstood.

“My son doesn’t eat. It would probably be a lot easier to be a picky eater,” she said. “This is not a behavioral problem or a mental health problem.

“It’s actually more of a hypersensitivity that leads to fear of trying food.”

The disorder was formally recognized in 2013, although it was previously recognized as a pediatric eating disorder in children under six years of age.

El Annan said he knew there was something different about the way Mohammad ate since he was a baby. Only last year was she able to get a formal diagnosis for Mohammad.

He said people with ARFID often don’t realize they are hungry until they are starving, but when they do eat, they don’t eat enough.

“This is the curve we keep going up and down,” he said. “It’s really challenging and exhausting for him.”

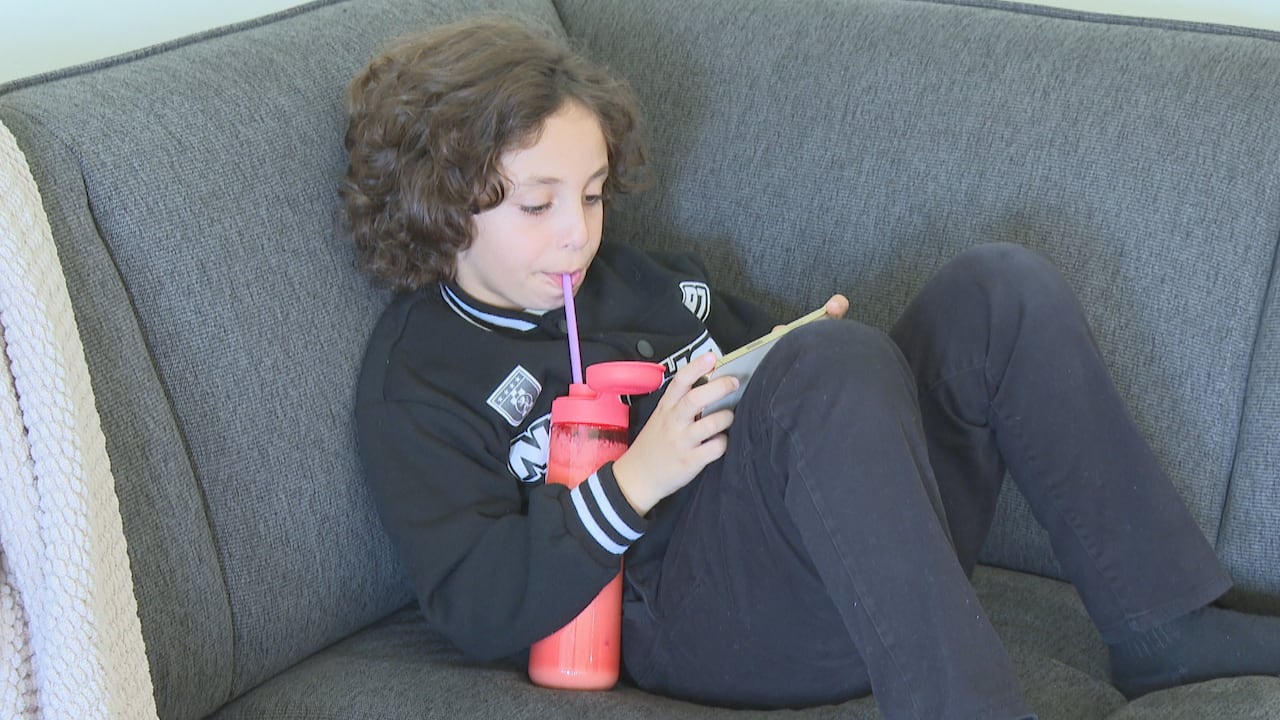

One Tuesday afternoon, El Annan offered his son a milkshake: milk with wheat powder, banana and vanilla pudding. While mixing it, he asked about the thickness. Good, he said. The color? Well too, said Mohammad.

While sipping the smoothie through a water bottle with a straw, El Annan decided to prepare an egg the way he likes it, at least for now: hard, with a little salt and a lot of cinnamon.

Sitting next to him, El Annan counted how many times he chewed, giving him lots of encouragement and gently encouraging him to take another bite or half a bite. The egg, not having consumed more than half when it seemed that Mohammad had had enough.

Small portions, breathing and facial exercises, and spending more time with meals help, she said, as do regular sessions with a therapist.

ARFID is a challenge for her, because of the time and intense effort it takes to make sure her son eats enough and gets enough nutrients, as well as providing all the therapy and extracurricular activities that will help him.

Mohammad said ARFID makes chewing and eating difficult.

But he says he’s learning more about ARFID and how to eat better.

“It makes me feel brave,” Mohammad said.

By speaking, El Annan says he hopes to connect with more families whose children struggle with ARFID, gain some recognition of the disorder in young children, and support for more services in the community. Help is available, but children with ARFID need more.

He also hopes for greater recognition within the education system, he says, because of the accommodations Mohammad needs at school, such as extra meal breaks.

Eventually, she hopes to start a program to help families with ARFID expose their children to more types of foods.

Most of the services around ARFID are for older teens and adults, and what El Annan can access is not covered by insurance and she pays out of pocket.

Annan says the biggest mistake is thinking that your child is simply picky or that this is something you can control.

“He tells me, ‘This is for you, I’m trying for you,’ because he’s seeing how much I’m giving him. And I tell him, you have to do it for yourself because this is for you to grow and be strong… it will keep you healthy.”

It’s a misconception that Heather Leblanc says is common among the adult clients she serves.

leblanc, a registered social worker with The Bulimia Anorexia Nervosa Association (BANA) in Windsor is part of the team that treats clients with ARFID through outpatient programs. Right now, they have about 10 adults receiving treatment.

There are three main types, he said, and sometimes people with ARFID will have a combination of all three: sensory sensitivity, such as an extreme aversion to the smell of food, fear of negative experiences, such as choking or vomiting, or a complete disinterest in food and lack of feelings of hunger.

There are no specific Windsor-Essex estimates for ARFID, but a Canadian study identified 2.02 cases per 100,000 pediatric patients.

Leblanc said the condition can be debilitating: For children, there are concerns about gaining adequate weight and maintaining a healthy weight, as well as nutrients for proper growth.

In adulthood, if left untreated, people with ARFID can lose hair and teeth or see their organs break down, as well as other medical complications due to nutritional deficiencies.

There are also social and psychological impacts: depression and anxiety are common and sometimes overlap with autism and obsessive-compulsive disorder.

“You may feel misunderstood. You don’t want to have to explain yourself,” he said. “It’s really sad because the alternative is just not participating in life. And for a lot of people, that seems like a safer option.”

It turns out that many ideas you had as a child about your body and your diet can affect how you feel about food today. Jennifer White is a clinical social worker specializing in eating disorders. During Eating Disorders Awareness Week, White speaks with CBC Windsor Morning’s Amy Dodge about what parents can do to break that cycle of negative thoughts about food and encourage body acceptance in their children.

Treatment for ARFID, he says, is very individualized, but at BANA it includes cognitive behavioral therapy with a team consisting of a psychologist, dietician, nurse practitioner and therapist with the goal of increasing “the volume and variety” of foods.

Services for youth with ARFID in the community begin at age 11 and BANA works specifically with adults. But Leblanc said she would urge parents to consult their pediatrician, and there are therapists and dietitians in the region who have ARFID training.

The first thing to know, Leblanc said, is that it’s not the person’s fault.

“For those who suffer from it, the anxiety and distress they feel around food is very, very real,” he said.

“My hope is that with people talking…people with ARFID and families who support people with ARFID will feel less ashamed and less alone.”

If you or someone you know is struggling with eating disorders, here is where you can seek help:

- Help phone for children: 1-800-668-6868. Text 686868. Live chat advice on the website.