For Canadians, Beaver is more than a rodent to teeth of dollars: it is a national emblem, recorded in five cents and in the center of the country’s history of origin. Now, a new study by the USA suggests that this symbolic animal can cause the arid western landscapes to be more resistant when leaving drought, slowing down floods and areas of protection of forest fires with the dams they build.

The study, conducted by researchers from Stanford University and the University of Minnesota and published in Nature, analyzed more than 1,500 Castor ponds in 40 currents in the west of the United States. The study found that the size of those ponds was not random. Instead, predictable rules linked to the length of the owner, the power of the current and the surrounding vegetation followed.

The findings add weight to a growing body of evidence that beavers can be acting as ecosystem engineers, remodeling the river routes so that they benefit not only their own survival, but that of the entire landscapes. By slowing the streams and extending the water in the flood plains, their prey creates lush habitat bags that can endure long after the fire or drought has dragged.

And as climate change promotes longer droughts, the heaviest floods and the most fierce forest fire seasons, researchers and land managers are looking for low -cost natural solutions to generate resilience. The study suggests that the Canadian icon could be part of the answer: intervene where human engineering cannot.

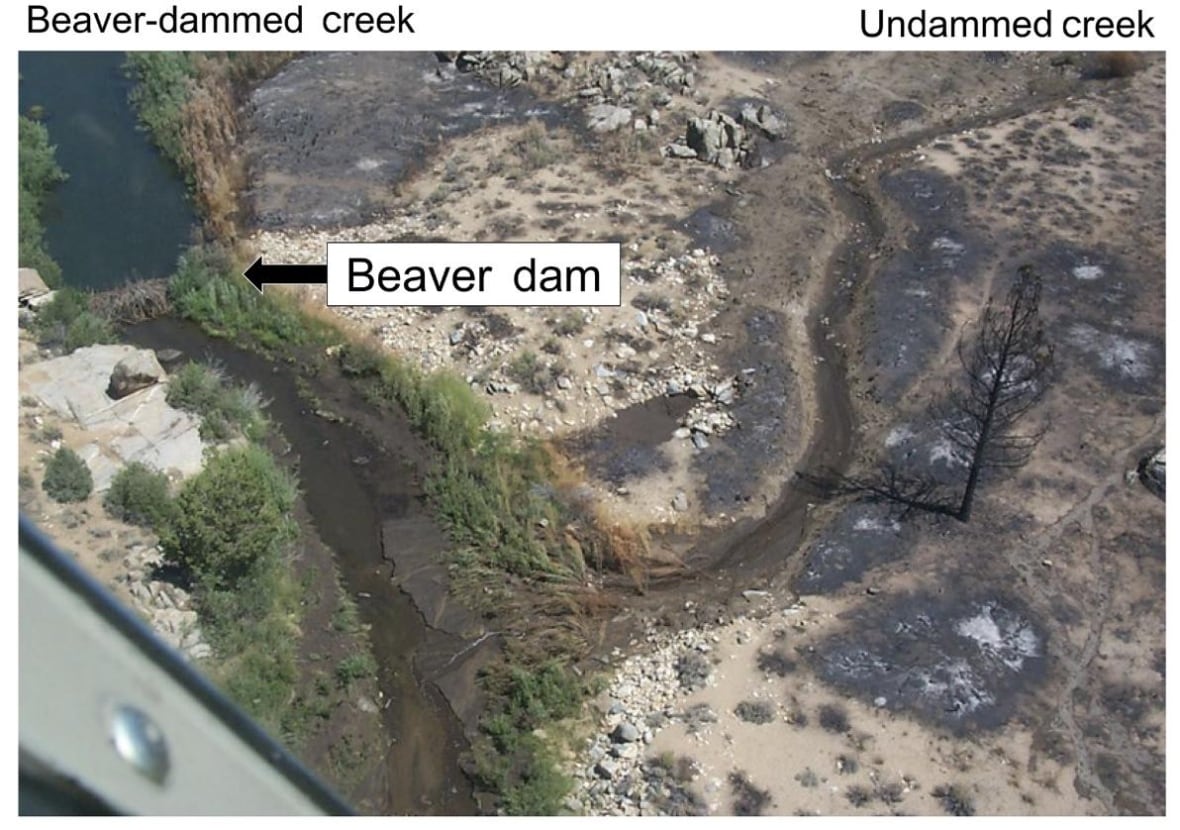

Aerial images reveal the scope of Beaver Engineering

To capture the full scope of Beaver Engineering, the researchers used aerial and satellite images to show how groups of dams that work in tandem can transform the landscapes.

“Aerial images are such a different perspective,” Emily Fairfax, a geography assistant professor at Minnesota University and one of the study researchers in an interview told CBC News.

On the ground, Beaver’s wetlands can take a full day to navigate, he said. But air images can reveal a landscape 10 times larger in minutes.

The study mapped more than a thousand Castor ponds in Colorado, Wyoming, Montana and Oregon, using aerial photos and water detection algorithms. The ponds that worked together were grouped in what the researchers called “complexes” and analyzed which environmental factors determined how large the ponds and dams were.

The researchers discovered that the weather, the soil and the management management form an important role, and that the largest prisoners created reliably larger wetlands.

For example, the ponds in the Northwest mountains were smaller than those of the big plains, probably because the mountains have narrower valleys and a different water flow. Work helps explain where beavers can succeed and how big their ponds can be.

Castor complexes such as ‘speed blows’ of forest fires

Castor’s complexes create more humid and green patches through a landscape. Fairfax compared the phenomenon of giving the landscape a mosaic of “speed blow” resistant to fire, allowing wildlife a place to take refuge and give ecosystems a springboard to recover more quickly.

In a 2020 study, the researchers found a visibly marked example of this during the 2000 Manter Fire in California, where an image showed that the vegetation near a Castor’s pond remained green while the surrounding areas burned.

This recently discovered power of Beavers is an abrupt turn of its historical role as a precious product in the early development of Canada. The animal’s skins forged the economic ties between European settlers and indigenous communities and tied the colonists west.

At one time, the overload of their thick skins led them to almost extinction, but the animals have returned notable, and not only in Canada. In the United Kingdom, where the beavers were taken to extinction during the Middle Ages, their reintroduction has caused environmental damage and has made them a nuisance.

The beales ‘can make a difference’

“It’s incredibly original,” said Marc-Andre Parisien, a scientist based in Edmonton who studies how forest fires extended through the landscapes with the Canadian forest service, on the recent study of Beaver Pond. He was not involved with the investigation.

“There have not been many studies on real effects … at the landscape level,” he said. “There is this fuel reduction that has been created by those beavers only by virtue of having that prey and the most greenish vegetation. Therefore, it can make a difference.”

However, he points out that given the size and intensity of some of the recent forest fires in Canada, not even the brave beaver has a possibility of stopping one dead on his way.

“You have a 50 -meter flame wall that moves quickly through the landscape; you can throw all the water you want in front of it. It’s like spitting in a fire,” he said. “I would not say that you can count on Beavers to stop large fires … but fragment the landscape in terms of fuel continuity, and you can work with that.”

Fire teams can treat Beaver’s ponds as natural anchor points, said Parisien, using the wettest patches to organize operations and slow down the propagation of flames.

Initially skeptical on the impact of Beaver’s wetlands, he said: “I think [the research has] He convinced me of that. “

In Ontario, where dozens of forest fires have burned thousands of hectares of forest this summer, the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry said that it will not bring more beavers to help.

“Casante populations are already widespread and abundant in Ontario,” said spokeswoman Sarah Fig in an email, adding that the ministry is not considering any relocation or reintroduction effort.