While the Percy Onabigon family extended the cedar and tobacco around its tomb, located more than 1,200 kilometers from its origin, Marcus Ryan said he never felt so overwhelmed by emotion.

Percy was taken from his family in Long Lake #58 First Nation in northern Ontario when he was a child and placed himself at the Indian residential school of San José in Thunder Bay. Due to its epilepsy and partial paralysis, it was sent to several institutions, including what was called Orillia Asylum for idiots, without the consent of their family.

In 1966, Percy died of tuberculosis at the Oxford Regional Center in Woodstock. I was 27 years old.

His family spent decades fighting to bring his remains back to the Long Lake #58. Next week, it is finally happening, with a traditional burial ceremony and a funeral mass planned for two days.

As Oxford County Guardian, where Percy was originally buried, Ryan said that knowing the Onabigon family has been a revealing experience.

“We all know that there are residential school denialists today, but there are also people who simply do not know,” Ryan said. “Especially in a community where you do not have a reservation and where there was no residential school, there is always the risk that some Oxford residents think:” Well, those were bad things, but they didn’t happen here. “

“While I was standing there with the family in the grave, I was thinking: ‘It happened here, I am looking at the grave. The family is here. This is where Percy ended.'”

Percy had a twin brother, Harold, who died when he was a baby.

Claire Onabigon, Percy’s niece, completed his thesis on the impact of the residential school system on Like #58 First Nation and the first neighboring nation of Ginoogaming. Through his research, he learned that four generations of his family were placed in the residential school system, including Percy, his mother Bertha and the Kenny and George.

After the exhumation of Percy in Woodstock this spring, its remains were sent to the Forensic Pathology Service of Ontario in Toronto, where an autopsy and DNA analysis were performed.

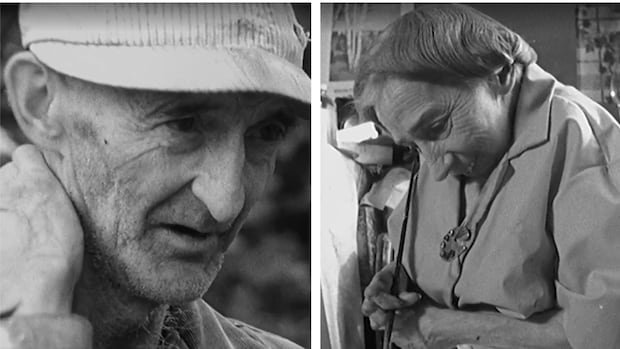

Superior tomorrowMarcus Ryan/Liz Dommasch: Percy Onabigon Memorial Exhibit

“It has been a long road on the road, sure for Percy. We met with the Forensic Chief, Forensic Pathologist and forensic anthropologist this week, and now we can make the final arrangements,” said Percy’s niece, Claire Onabigon, in a press release issued by Oxford County at the beginning of September.

Meanwhile, Ryan came up with the idea of honoring Percy locally with a special exhibition. With the family blessing, the archive team has established four showcases in the Oxford County Administration Building.

“It was an honor to be asked to do so, just knowing that there is so much behind, not only as a story, but so many bigger problems,” said Oxford County Archivist Liz Dommasch.

The process involved communicating with files and ontarium museums that provided documents, as well as indigenous artifacts.

“We just wanted to make sure we were doing well and we were honoring Percy’s legacy in the process,” Dommasch said.

‘Steps towards reconciliation’

The exhibition consists of four glass boxes, each of which telling a different part of the history of Percy. He begins with an introduction to Percy and his family in Long Lake #58 while telling the indigenous history of Oxford County.

Then, it presents the experience of Percy at the Indian residential school of St. Joseph, as well as information on the residential schools closest to Oxford County. The third case highlights the story behind the institutions to which Percy was sent, with the final piece highlighting his family’s efforts to repatriate his remains.

“We also play some of the greatest problems … of denial, as I know, unfortunately, there has been a bit of online setback over all the repatriation of Percy,” Dommasch said.

“It provides a series of resources that people can consider whether they want to learn more, not only about residential schools and truth and reconciliation. [but] Broader and general general context that leads to September 30 “.

September 30 is the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation – A federal legal festival in Canada that aims to recognize the lasting legacy of the residential school system. and honor the survivors and those who never came home.

“As Archiveros, our work is to preserve historical records and make sure the stories do not forget,” Dommasch said. “I think this is a story that must definitely tell again and again.”

The exhibition, which has been updated since the beginning of September, will be withdrawn after a closing ceremony of October 6 with members of the Onabigon family and other dignitaries.

“This [display] It means a lot to us and is very appreciated. Thank you, Oxford County, for taking these steps towards reconciliation, “said Claire Onabigon.

A line of crisis of the Indian National Residential School has been established has been established to provide support to former students already affected. People can access emotional services and crisis reference by calling the national crisis line 24 hours: 1-866-925-4419.

Mental health advice and crisis support are also available 24 hours a day, seven days a week through the HOPE for Wellness Direct Line at 1-855-242-3310 or by online chat www.hopeforwellness.ca.