Over the next five years, up to 100,000 people in Ontario will be tested for genetic conditions that increase the risk of hereditary cancers and a condition linked to high cholesterol and heart disease, says Princess Margaret Cancer Centre.

In what the hospital calls one of the largest population genomics studies in Canada, the project combines screening results to allow participants and their healthcare team to make decisions to potentially delay, reduce or prevent cancer and heart disease. At the same time, hospital researchers gain a rich set of data that they can combine with patient information, which could help address those with disproportionate health risks.

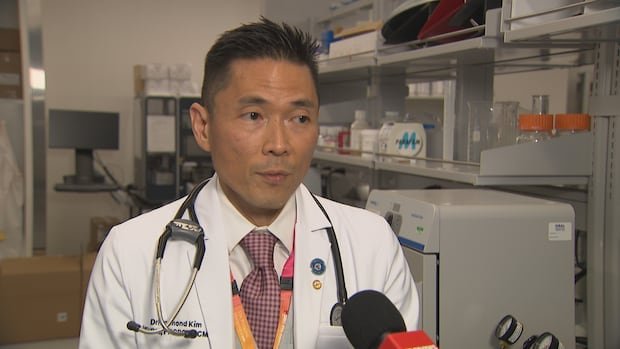

The first participants will be cancer patients at the hospital who may have genetic risks that could influence their treatment or how they are monitored, said Dr. Raymond Kim, medical director of cancer early detection at Princess Margaret.

“Yes, these patients have cancer, but we don’t know their genetic makeup,” Kim said. “Knowing their genetic makeup helps them see if [doctors] “We have to worry about any other cancer.”

Knowledge the towns genetic composition can alert doctors to the risks and influence next steps in treatment, Kim said, noting that people with BRCA mutations are recommended to start monitoring their breasts in their 20s. Or if someone has a genetic variant for lynch syndrome, which associated with colorectal cancer and other types of cancer, they may need colonoscopies, he said.

Leslie Born, a patient who participated in a previous research project at the hospital, was diagnosed with advanced ovarian cancer in March 2020 that had spread to the lining of her stomach. She was treated with surgery and chemotherapy.

Born had no immediate family history of cancer, but was screened for a variety of mutations associated with cancer.

“I received the news that I had a BRCA2 genetic mutation after my surgery and biopsy results,” Born said. “That was a shock. I had no idea.”

The BRCA2 gene provides instructions for making a protein that acts as a tumor suppressor. People with a BRCA2 mutation face an increased risk of certain cancers, including breast, ovarian, prostate, pancreatic, and melanoma.

Born now receives a breast MRI and mammogram every year as part of surveillance. Without the genomic information, she and her doctors wouldn’t know what was needed, Kim said.

Expand the net for genetic testing

Because family sizes are on average smaller than in previous generations, traditional methods for identifying high-risk families can miss many individuals, says Laura Palma, a certified genetic counselor at the McGill University Health Center in Montreal, who is not involved in the project.

“Some of these families are not so easy to identify,” he said Palm. “Widening the net in terms of access to genetic testing might be the best strategy moving forward.”

Palma says it will be interesting to see the project’s findings and what participants do with the information, such as changing eating habits or physical activity levels.

Genome testing and the care that follows will have costs, and palm says The profitability will not be immediately clear.

“I think we need those studies in Canada to really see: can our system absorb a model like that? Does it make sense for taxpayers?” Palma said.

After genetic testing revealed that two Saskatchewan sisters had a mutation that increased their chances of developing a deadly type of stomach cancer, they face agonizing decisions to save their lives.

Like Palma, Jenna Scott, co-director of the master’s program in genetic counseling at the University of British Columbia, welcomed the “fantastic” project.

According to Scott, the cost of genomic testing has dropped and become simpler, such as using mouthwash instead of blood draws to collect the DNA sample. But he also has questions about expanding the project on a broader scale while also understanding cultural needs.

“If I am an Indigenous patient and live in a remote rural community, how can I have a breast MRI? Is there any funding to help me get to the urban centers where the exam is performed?” she said.

The researchers will share the results with participants and hope to use the data collected to find out how useful this type of broader screening could be and for whom. Kim has her sights set on enrolling not only patients in the Toronto University Health Network, but also those referred by family doctors.

Relatives of patients, including those with familial hypercholesterolemia, an inherited condition associated with high cholesterol and cardiovascular risk, will be offered personalized counseling, monitoring and treatments when appropriate, Kim said.

Helix, a biotechnology company based in San Mateo, California, is a partner in the project. Kim said the hospital’s research ethics board worked diligently to ensure people’s privacy was protected.