The withdrawal from Russia of Napoleon Bonaparte and the French Grande Armée in 1812 was a catastrophic event that marked the beginning of the end of his empire and his personal rule in Europe, with the death of some 300,000 soldiers in a force that originally numbered approximately half a million.

A new study using DNA extracted from the teeth of 13 French soldiers who were buried in a mass grave in Vilnius, the capital of Lithuania, along the retreat route, offers a deeper understanding of the misery experienced by the Grande Armée, detecting two previously undocumented pathogens in this event.

The discovery of the bacteria that cause paratyphoid fever and relapsing fever transmitted by lice demonstrated, along with previous work, that several infections had circulated among soldiers already weakened by cold, hunger and fatigue.

The Vilnius site, discovered in 2001, contains the remains of approximately 2,000 to 3,000 soldiers from Napoleon’s army.

“Vilnius was a key point on the retreat route of 1812. Many soldiers arrived exhausted, hungry and sick. A substantial number died there and were quickly buried in mass graves,” said molecular biologist and geneticist Nicolas Rascovan, head of the microbial paleogenomics unit at the Pasteur Institute in Paris and lead author of the study published in the journal Current Biology.

“While the emphasis has long been on cold, hunger and typhus, our results show that paratyphoid fever and lice-borne relapsing fever were also present and may have contributed to debilitation and mortality,” Rascovan added.

Paratyphoid fever is usually transmitted through food or water, and its symptoms include fever, headache, abdominal pain, diarrhea or constipation, weakness, and sometimes a rash. The form of relapsing fever detected is transmitted by body lice and causes episodes of recurrent high fever, with headache, muscle aches and weakness.

In the study, four of the 13 soldiers tested positive for paratyphoid fever bacteria and two for relapsing fever bacteria. The symptoms of the two ailments coincide with those described in historical accounts of the retreat.

A 2006 study using the DNA of 35 other soldiers from the same cemetery detected the pathogens behind typhus and trench fever, diseases that cause symptoms similar to those of paratyphoid fever and relapsing fever. The new study did not detect typhus or trench fever.

Napoleon led the Grande Armée in an invasion of Russia in 1812 and marched towards Moscow, but the campaign collapsed and he was forced to retreat thanks to factors such as supply shortages, counterattacks, and the onset of the brutal Russian winter.

The new findings add nuance to the story of the plight of the French emperor’s soldiers, pointing to a scenario not of one or two ailments in circulation, but rather of a high prevalence of various infectious diseases. The study does not quantify the overall impact of the newly identified pathogens or establish their distribution throughout the military, but it helps explain the medical complexity of the drawdown.

“Ancient DNA allows us to put names to infections that symptom-based explanations alone cannot resolve. The coexistence of pathogens with different transmission routes underlines how dire the sanitary conditions were,” Rascovan said. “Future work on more sites and individuals will refine the picture of the 1812 disease.”

The study illustrates how the constantly improving science of ancient DNA analysis can provide new insights into historical events.

“Ancient DNA allows us to test historical hypotheses directly, adding evidence that can confirm or complicate narratives constructed from chronicles and symptoms,” Rascovan said.

“With careful authentication, genomics reveals what pathogens were present, how they evolved and persisted, and how they spread, helping historians and scientists reconstruct complex crises with greater resolution.”

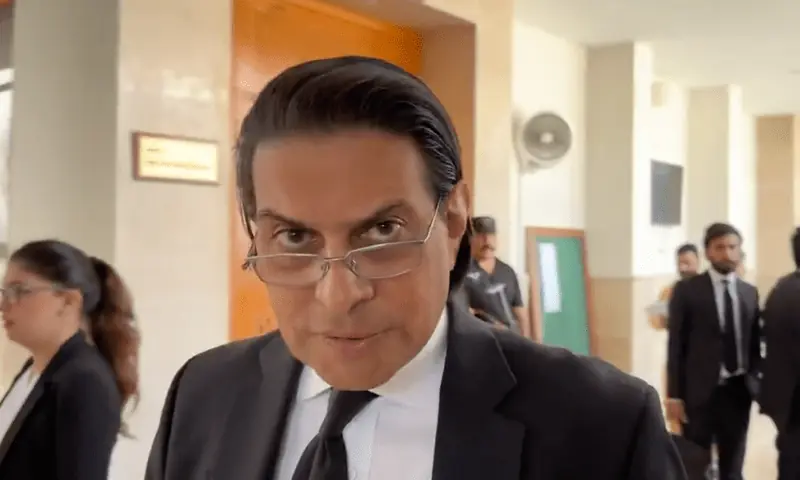

Header image: People sit in front of the 1802 painting “Le Premier Consul franchissant le Grand-Saint-Bernard” by French artist Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825) as they visit the “Napoleon and Europe” exhibition at the Musee de l’Armée (Army Museum) at Les Invalides in Paris, France, March 26, 2013. — Reuters/File