Tract representatives have brilliantly launched the project to residents, saying that the center will be “a good neighbor” while generating hundreds of millions of dollars for the local government.

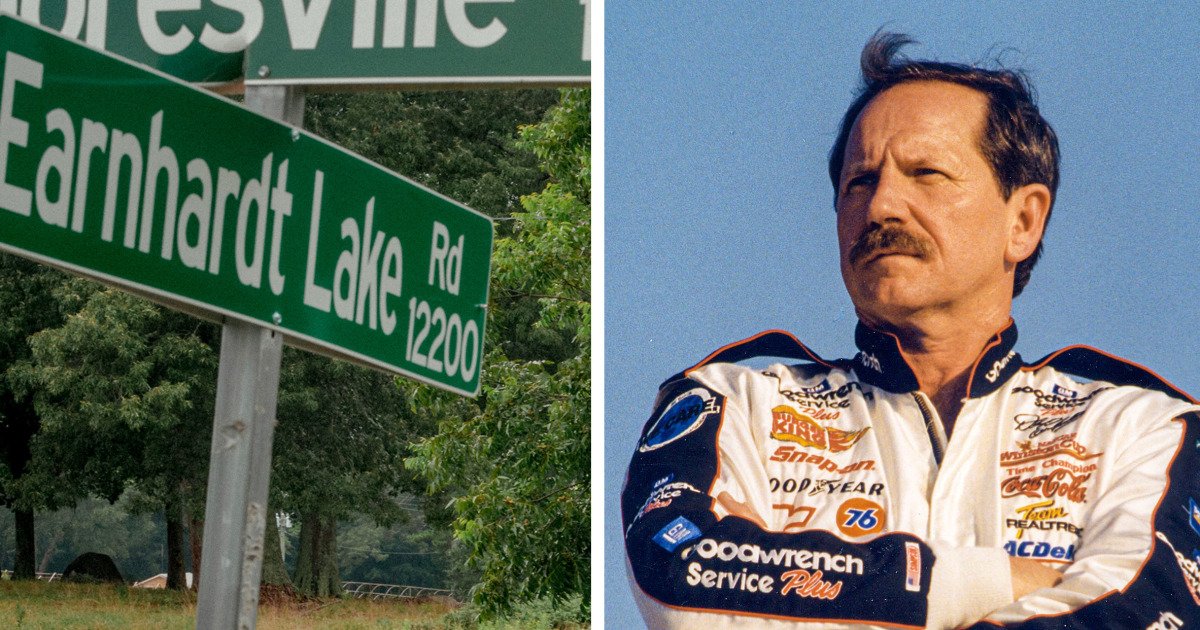

Leaving aside the family disputes of Earnhardt, the fight in Mooresville echoes similar debates throughout the country as communities deal with possible economic benefits and environmental disadvantages of giant data centers that swallow land and resources to feed the insatiable demand for computer power.

The multitudes of people have packed Arizona meetings to Alabama to express fears that these projects can overcome the electricity grid, contaminate water and air and, in general, interrupt their rural peace with structures that emit a high technology buzz. Supporters, who often include local officials and business development groups, present data centers as a way of infusing economic opportunities and tax revenues in areas with difficulties and making good land use that would otherwise be vacancies.

The White House also praises the projects in the midst of the country’s artificial intelligence career against China. In July, President Donald Trump signed an executive order to accelerate federal permits for data centers.

There are already more than 5,400 data centers in the United States, with many more on their way. The McKinsey consulting company said in April that it predicts approximately $ 7 billion in global expenses in data centers in the next five years, it largely caused the demand for processing power to meet the needs of technological companies that are composed to build and develop advanced artificial intelligence systems.

Data centers, often massive buildings dedicated to the capacity of computer science and data storage, can force local energy and water resources. A study by the Institute of Environmental and Energy Study found that large data centers can consume up to 5 million gallons of water per day.

While the need for technology companies of data centers is only growing, the opponents of these projects have begun to advance the arrest. In Arizona, the Tucson City Council voted Wednesday against the Project Blue Data Center in Amazon, worried that it would increase public services costs. In Oldham County, Kentucky, a data centers developer withdrew from a project last month and the County Tax Court approved a moratorium on the data centers after the community setback on environmental concerns.

Data Center Watch, a group financed by the firm of the 10A Labs that tracks the local opposition, found in May that $ 64 billion in data centers developments in the US. UU. Had been blocked or delayed in the previous year.

“The volume, speed and effectiveness of the local opposition are remodeling the panorama of political risks for the data center industry,” said Data Center Watch in a statement to NBC News.

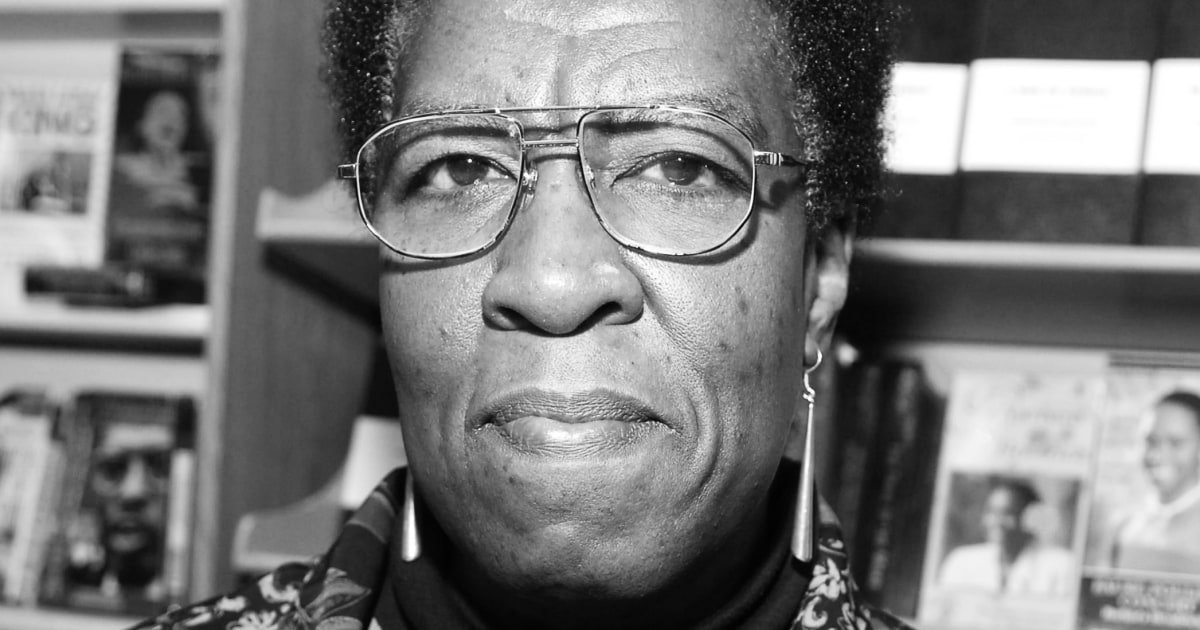

Wendy Reigel, activist in Chesterton, Indiana, routinely gives advice to other communities to fight the data centers after a successful movement began against a project of $ 1.3 billion in its city last year. She tells those who ask for help that developers often present to the centers as a treatment made, but that is not the case.

“In the end, people need hope,” he said, “and then need information, and then they had to work their rear ends.”

That is what the organizers in Mooresville have been doing. Around 200 people filled a meeting of the Commissioner Board last Monday, many with red shirts to point out their opposition to the project. The 10 people who spoke at the meeting expressed concerns, questioning the promises of the tract about the works and care about the demand of the center of the center in a region prone to drought.

“Does a data center belong to the middle of a prosperous rural residential community?” Kerry Pennell, who lives near the proposed site, later said. She helped distribute around 170 grass signs “No Data Center” that now splashed the surrounding roads. “I don’t want an industrial wasteland at a mile from my house,” he said. “I can listen to crickets at night.”