Millions of years ago, a pony-sized hornless rhino roamed the forests and chewed on leaves in what is now northern Nunavut, making it the northernmost rhino ever found.

A new study published Tuesday identifies it as a new species and offers an intriguing explanation for how it got there.

Epiatheracerium itjilik It was about the size of a modern Indian rhino and much smaller than an African rhino, measuring about three feet at the shoulder, said Danielle Fraser, lead author of the new study published in the journal Nature Ecology and Evolution.

Researchers found more than 70 percent of the animal’s skeleton in Haughton Crater on Devon Island, about 1,000 kilometers north of the Arctic Circle, breaking the record for the northernmost rhino set previously by a specimen from the Yukon.

From his skull, teeth, and other bones, they were able to learn a lot about him.

The wear and tear of his teeth showed that he was in early to middle adulthood.

Natalia Rybczynski, a paleobiologist at the Museum of Nature and Carleton University who co-authored the new study, said researchers believe the rhino was a female. This is due to the small size of some lower teeth which tend to be much larger in male rhinos.

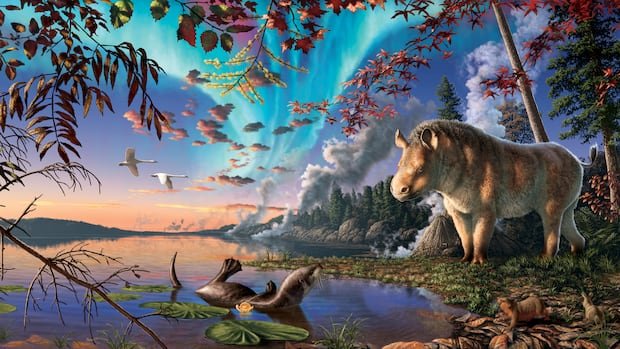

In an artist’s reconstruction, a hairy rhinoceros with widely spaced nostrils and no horns stands at the edge of a lake near lilies, swans and an otter-like creature. In the background is a forest of pine and spruce, along with maple, birch and alder in autumn colors, and the northern lights break through the twilight sky.

“I wanted the artist to make the rhino look like a pony in winter,” said Fraser, head of paleobiology at the Canadian Museum of Nature in Ottawa.

While the climate was similar to southern Ontario today, the winters would have been snowy, and Fraser reasoned that the animal would have had to stay warm during the long, dark winters in its polar home.

In fact, its species name is the Inuktitut word for “frost” or “frost” and was chosen by Jarloo Kigutak, an Inuit elder from Grise Fiord who worked with some of the paleontologists on fossil collecting trips to Devon Island and Ellesmere Island.

Fraser said the new species walked on four toes instead of the three used by most rhinos: “It’s a bit strange in that way.”

Interestingly, the fact that it was hornless is not unusual: most fossil rhinos were hornless, despite the name “horned nose” that comes from their modern descendants.

Overall, however, the new species is quite different from the dozens of fossil rhino species that roamed North America. Instead, it has been added to a genus of similar species found in Europe, Epiateracerium.

That raised questions about how he ended up on Devon Island. Previous studies suggested there was a land bridge between Europe and North America, but it broke down about 33 million years earlier. E. itjilik vivid.

The researchers propose that the discovery of this rhino provides evidence that some animals were still able to cross during the Early Miocene, even though there was water between islands at that time.

“In different time periods… it’s possible that there was actually some ice there in the winter that allowed them to cross,” Fraser said.

A wait of 40 years

While E. itijlik has just become a new species, its first bones were discovered four decades ago by Mary Dawson, paleontologist and curator at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History, posthumous co-author of the new study, after having died in 2020.

The lake where E. itijlik I drank once in Haughton Crater, a huge pit created by an asteroid impact on Devon Island. The artist’s impression of the rhino includes background steam from hydrothermal vents believed to have opened due to the impact.

The lake has long since dried up, leaving behind a polar desert that has been a rich source of fossil fragments, Rybczynski says.

Fossils found there include many fish, swans, ducks, an otter-like ancestor of seals, “tons of” rabbits and a shrew, many of which appear in the artist’s reconstruction.

It was a time when many types of horses, camels, rhinos, and large predators such as saber-toothed cats roamed North America, although so far the rhinoceros is the only large animal found in Haughton Crater.

The Arctic’s freeze-thaw cycles cause the soil there to frequently churn, rising to the surface, burying and scattering bone fragments over wide areas.

Paleontologists dig them out of the dusty ground, then bag them and take them back to the museum. But putting them back together can be a long and challenging process. Rybczynski said that when the bones are placed, “on one side we have a table of remains” that researchers hope to identify and place someday.

When Dawson found the first rhino bones in 1986, he knew immediately that it was a rhino, since rhinos have distinctive bands on their teeth, Fraser said.

After returning to the Carnegie Museum, Dawson showed the bones to some fossil rhino experts. One of them was Donald Prothero, a professor of geosciences at California Polytechnic State University, who has since written a book on fossil rhinos.

He noted that the animal’s teeth and four toes resembled those found in some very ancient rhinos, but none as young as 23 million years ago.

“I said, ‘Well, this is a very strange animal, good luck,'” Prothero recalled.

He suggests that’s one of the reasons it took so long to study it thoroughly.

A team including Dawson and Rybczynski returned to the fossil site several times in the late 2000s and eventually managed to find about 70 percent of the skeleton.

Jaelyn Eberle, a Canadian paleontologist at the University of Colorado Boulder who studies Arctic mammal fossils, said it is very unusual to find such a complete fossil skeleton, especially in the Arctic. Most of the time, only “small pieces, fragments, maybe part of a jaw, maybe a single tooth” are found.

She said given the amount of the animal they had, she feels confident in the results.

Both she and Prothero said they were intrigued by the study’s suggestion that animals used a land bridge between Europe and Asia for much longer than previously thought.

“That’s pretty interesting and exciting,” Eberle said, adding that it makes him want to look for more evidence of animals crossing in that region.

Like Prothero, she and other fossil mammals have long known about this fossil rhino and are excited to learn more.

“We were waiting for him.”