The port city has witnessed 55 cases of lynching in the last three years, with experts who attribute the tendency to the lack of confidence in the police, the courts and the justice system.

It was in the tumultuous decade of the 2000s that Karachi and I witnessed our first lynching. In the area of the ancient city of Nishtar Road, three “thieves” of the street were arrested, beaten and flames by an enraged mafia.

The incident took place on May 14, 2008, on Wednesday, when four men broke into an apartment, looted value objects and opened fire against residents. While they fled, the family called the alarm, calling the attention of the neighbors. Subsequently, a persecution began, ending only when the thieves were finally cornered by the crowd that had gathered at that time.

And then all hell was released. While one of the suspects managed to escape, the remaining three men were beaten by all and all available for the crowd: canes, iron bars, bricks, kicks and blows. They were dragged to the main road later, where gasoline were thrown and a phosphorus was lit.

While the flames wrapped the thieves, the police were close and observed. So did the volunteers of the Edhi Foundation because the crowd did not allow them to rescue men. It was not clear if the three men had died before they were burned or succumbed to it.

For me, it was difficult to understand what happened that day; An angry group of people developed all the roles of prosecution, jury and judging in the street.

As a reporter of the crime in the metropolitan city of Karachi, I had acclimatized to explosions and bloody bodies full of gunshot wounds, but lynch, where the suspects were beaten and burned on behalf of justice.

I knew little that a decade later, such incidents would become routine, more or less to say.

The emergence of the “justice” of the mafia

According to the data compiled by the Liaison Committee of the Citizen Police, around 100 people lost their lives while resisting the incidents of theft in Karachi in 2024. He also highlighted a remarkable increase in the number of gangs involved in street crimes, with their number from 20-35 to 50-60.

With the growing crime, lynching have also increased in the city. According to the Pakistan Human Rights Commission (HRCP), 55 suspects were lynching in the streets of Karachi in the last three years; 20 each in 2023 and 2024 and 15 in 2022.

“There are a number of factors behind the escalation of this so -called Mafia Justice,” said Dr. Zoha Waseem, an assistant professor of Criminology at the University of Warwick, England. “The lack of confidence in the police, the courts and the criminal justice system in general is partly the problem.”

An incident of lynching that remains fresh in my memory is the murder of two sialkot brothers, which left the country shocked. Mughees, 17, and Muned, 15, were lynching by a mafia in broad daylight in Butran Wali, in view of police officers who did not make any attempt to stop the murders.

The brothers were declared thieves, their bodies were dragged through the streets and hanging against a water tank. The mafia was about to set them fire when the members of the adolescents’ family arrived at the scene and took them home.

Perhaps it was one of the rare incidents of lynching where the seven people accused of lynching received a death sentence, six years of life imprisonment. The police present at the scene were sent to jail for three years.

The incident also led two students from a private university to carry out a study called ‘Psychology behind the tragedy of Sialkot’, which was published by an international magazine in 2018.

Written by Farheen Nasir and Khadeja Naim, the Institute of Science and Technology of the Social Sciences of Shaheed Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, the document pointed out: “It seems that, in general, our society is becoming corrupt and evil and evil, where people lose self -control, feelings of empathy, confidence in others and while enjoying other sufferings.”

In addition, he stressed that some of the most atrocious actions and insidious behaviors can be attributed to the interaction of the dynamics that question their morals, ignore their values and commit to acts of those who would never have been considered capable.

The analysis showed that the common causes of human evil come from disappointment, inaction against evil committed by others, propaganda to distinguish itself from others, psychological distancing, rationalization, semantic framework and stereotypical labeling, resulting in dehumanization.

The investigation recommended that the future roads must include an approach in the studies carried out in the nations in which such horrible acts of violence are rarely found to discover which social values follow and the procedure to instill in their nation.

Where the legal system fails

For the layman, Lynching is a fair treatment and the rapid justice, said Muhammad Ali Qasim, a main defender of the Sindh Superior Court.

“But for a man of the law, it is a view of the disaster and sufficient evidence for the legal system to be failing somewhere, which leads to the public to resort to such measures,” he said.

In the current civilized world, the spill of unfair blood, the chaos and the disorder of the primary times have been replaced by the justice of the Court of First Instance. The reason itself behind the existence of a legal system is to stop violence and protect innocent lives. He is also intended to punish criminals according to the seriousness of their crimes.

“And this is what supreme should reign in the civic and civilized world, not street justice,” Qasim emphasized.

For its part, the police believe that lynching incidents are largely reported in less educated areas and neighborhoods. “The public tolerance in recent years has been reduced and all they need is a trigger to eliminate anger,” said Zeeshan Siddiqui, a main superintendent of the Central District of Karachi.

He stressed that it was the priority of the police to avoid such a situation in the first place and do everything possible to rescue the suspects from the Mafia clutches. Citing the example of the Central District, the SSP said that a single incident of lynching in one year had not taken place.

That, however, does not decrease the seriousness of the problem in the city. On April 10, nine dumpers and water oil tankers were burned in angry mobs near the main artillery that leads to Chowrangi 4 km after a heavy vehicle hit and wounded a motorist in northern Karachi. They were angry at the growing traffic incidents in the city. According to the police, the mafia also threw stones at fire trucks when they tried to turn off the fire.

Only two days later, another water tank truck was burned in northern Nazimabad. In a statement, the police said the driver had hit a motorcyclist near Popsy Nagar and fled the scene along with the vehicle. However, a group of 10-12 people persecuted him and intercepted him near the five-star Chowrangi. They attacked the driver and damaged the oil windows before burning it.

Separately, last month, a thief was captured and beaten after he killed a merchant in the Quaidabad area. He suffered serious injuries and was taken to the Jinnah Postgraduate Medical Center (JPMC), where doctors declared him dead upon arrival.

In a similar incident in November last year, another alleged thief was beaten until death in Gulistan-i-Jauhar. In May, the Police of the city of Orangi rescued an alleged thief to be burned alive for a mafia.

Restoring public confidence

Dr. Waseem of the University of Warwick highlighted socioeconomic disparity as among the main causes behind the increase in the incidents of the justice of the mafia. “People are frustrated due to inflation, class divisions and their lack of access to basic services,” he said.

This frustration, the academic continued, was increasingly in anger.

“You cannot separate the political-religious landscape of this country from socioeconomic disparities and broader dysfunctions within the criminal justice system that collectively are responsible for the increase in the mobs of the lynchings and the violence of the mafia in Karachi or other cities of Pakistan,” he added.

The first time Karachi witnessed a lynching, in 2008, triggered a domino effect. Only a few days later, on May 18, two alleged thieves were mistreated and burned by a mafia in northern Nazimabad. Following the incident, the then Chief of Police of Sindh, Dr. Shoaib Suddle, admitted that people were convinced that the system, which is supposed to give them justice, had never responded to their complaints.

In the following days, the newspapers led holders as “Karachi Mob Justice worries the government”, “Law of the Jungle?” etc. Clearly, it was a situation never seen before.

“Each incident stands out as a marked accusation of the justice system and should serve as a call for attention for politicians, legal professionals, political and social leaders and civil society activists,” Abdul Khaliq Shaikh, former Inspector General of Baluchistan, observed, who spent most of his service in Sindh and Karachi.

“Urgent reforms are needed to restore public confidence in the legal process and cultivate a culture of tolerance and respect for the law,” added the senior officer.

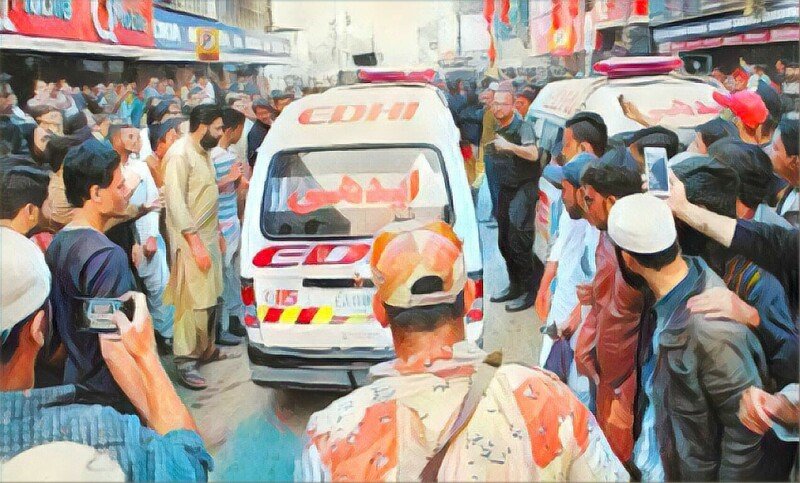

Image of heading: Security staff and merchants meet in the Saddar electronic market area after a lynching incident. – PPI