Alberta is planning legislative changes that would allow people to pay out of pocket for diagnostic and preventive tests, such as MRIs, CT scans and full-body scans, without a doctor’s order.

Some private testing is now available in Alberta. However, the government says options are currently limited, adding that if a privately purchased test reveals an important or critical condition, then the out-of-pocket cost will be reimbursed, “ensuring no Albertan pays for a medically necessary test.”

The government maintains that the measure will increase availability and relieve pressure on public resources, while improving early detection and health outcomes.

Adriana LaGrange, Alberta’s minister of primary and preventive health services, framed the plan as a modernization push.

“We want to see an outpouring of investment and healthcare professionals in Alberta to strengthen our preventative healthcare system for Albertans across the province,” LaGrange said in a government video. “This will help us do that.”

But some warned the plan could end up leaving more Albertans behind and putting more pressure on the public health system.

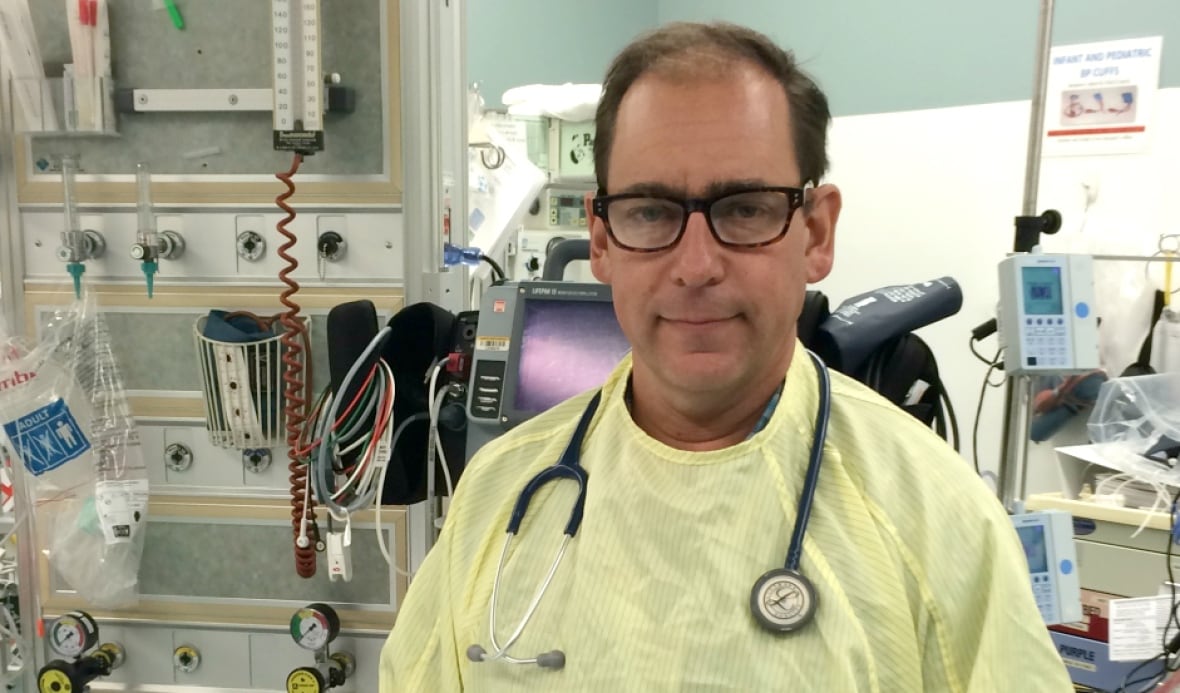

“This will have major ramifications and completely collapse our public health care system, and absolutely set up a system where those who have resources and money will receive much better and faster care,” said Dr. Paul Parks, president-elect of the emergency medicine section of the Alberta Medical Association.

Officials added that doctor-recommended testing would “continue to be fully covered and prioritized in all facilities, public or private.”

About the number of technicians available

The problem at hand has nothing to do with a lack of technicians, according to Alberta Premier Danielle Smith. The problem is that Alberta only pays for a certain number of procedures, he said Thursday.

“[Alberta Health Services]When they managed all this, they rationed care. And as a result, we know we have unused capacity. “We want to be able to use all the capacity and also have people be able to get preventative and diagnostic testing,” Smith said.

“But the most important thing is that if someone finds something, we want to reimburse them and get them into treatment… right now, that’s not happening.”

Some, including Renaud Brossard, vice-president of communications at the Montreal Economic Institute, are optimistic about the idea.

“Every time someone goes to a private testing center, well, that’s one less person waiting in line at one of those public facilities. It helps reduce wait lists in both sectors,” he said.

“And again, the earlier we can detect a disease, the earlier we can detect a condition, the earlier it can be treated, the less expensive it will be to treat and, of course, the less the patient will suffer.”

Parks disagrees. He said the biggest hurdle in Alberta’s diagnostic system is not a shortage of machines, but a shortage of trained technologists.

He said if the government expands private pay pictures, those technicians will be attracted to higher-paying private jobs, nine to five, rather than working nights and weekends in hospitals.

“Right now, we can’t get technicians to work in our hospitals because it’s a harder job, it’s after hours, it’s weekends,” Parks said. “As soon as the government opens this up for paid private ultrasounds, for example, all our technicians will be gone.”

Alberta already has a division for MRIs, he said, and it’s a “perfect example of where there is inequality.”

“Private paying access to MRI is measured in days in Alberta…Right now it’s measured in months or years in the public paying system,” Parks said.

In a statement, a spokesperson for LaGrange said new workers are “constantly coming to Alberta and graduating from training programs.”

“When we fund a new publicly funded hospital or increase the budget to pay for more family physicians, new jobs are created for staff and, over time, the workforce expands and fills those positions,” the statement read.

“Of course, there are shortages; all growth increases the demand for workers, which sometimes cannot be met immediately. This applies equally to growth in the public and private sectors.

“The idea that new private sector jobs ‘steal’ workers from a fixed pool and leave no one working in public facilities is a meaningless talking point for ideological opponents of any private service.”

Preventative benefit likely minimal: doctor

Dr. Eddy Lang, an emergency physician with the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Healthcare, said this move could, in theory, create more jobs and improve bottom lines for companies doing this work.

“But don’t tell me you’re going to prevent future hospitalizations and cancers by offering this service. That’s only true in a very, very select number of conditions,” he said.

Lang said that while full-body CT scans or MRIs may look appealing, they often uncover harmless, incidental things or “incidentalomas,” abnormalities that would never have caused problems if they had not been discovered.

However, once detected, patients can end up in a cycle of follow-up scans, biopsies and unnecessary anxiety, he said.

“I can understand the financial incentive, but I’m really concerned about the scientific basis for opening up and making access to preventative screenings, scans and MRIs free for everyone. I think that could be very dangerous.”

In a statement, a spokesperson for LaGrange said many Albertans only go to the doctor once a problem arises, at which time some conditions may be more difficult to treat or detect. Therefore, increasing access to preventive testing can detect problems earlier and improve health outcomes.

“We do not agree that this will create further delays. Greater control over preventive health screenings can save and improve lives,” the statement read.

Meanwhile, patients stuck in long waits are watching closely. Isabelle Cliche, a 47-year-old Calgary mother of three with debilitating hand pain, said she is scheduled for an MRI in August 2027.

“Just think about everything you need your hands for, right? Like holding a book or just turning the page,” Cliche said.

The province said it will consult stakeholders on the changes and outline any legislative and policy amendments needed to expand preventative screening options, with updates expected in the first half of 2026.