I’ve spent the last few weeks staring at what appear to be digital ghosts; They look human, they talk like us and provoke anger and despair. But they are not real. They are machines that wear human skin.

Something is changing in Pakistan’s social media landscape. It’s not just a rumor. It’s not the old misinformation cycle. It feels darker. Artificial intelligence is reshaping reality frame by frame until the Internet looks like a hall of mirrors.

For me, it started on November 8, when an account called ‘PakVocals’ posted a video on X purporting to show journalist Benazir Shah dancing in a nightclub. The title was cruel. He tried to mock her by using derogatory comments against her professional credibility. As of this writing, that video has garnered more than half a million views.

It did exactly what it was designed to do: make a journalist a target. Mission accomplished!

To most viewers, the clip probably passed as real, but to me, something felt off.

When the mask slips

I opened the clip in DaVinci Resolve, a video editing software that can be downloaded online, and watched it frame by frame because deepfakes are rarely perfect; They usually leave little crumbs of evidence.

And on frame 30, I found it!

For a split second, the skin tone wavered. The outline of the face rippled like water. Apparently, the mask had slipped: a clear sign of facial manipulation had been identified.

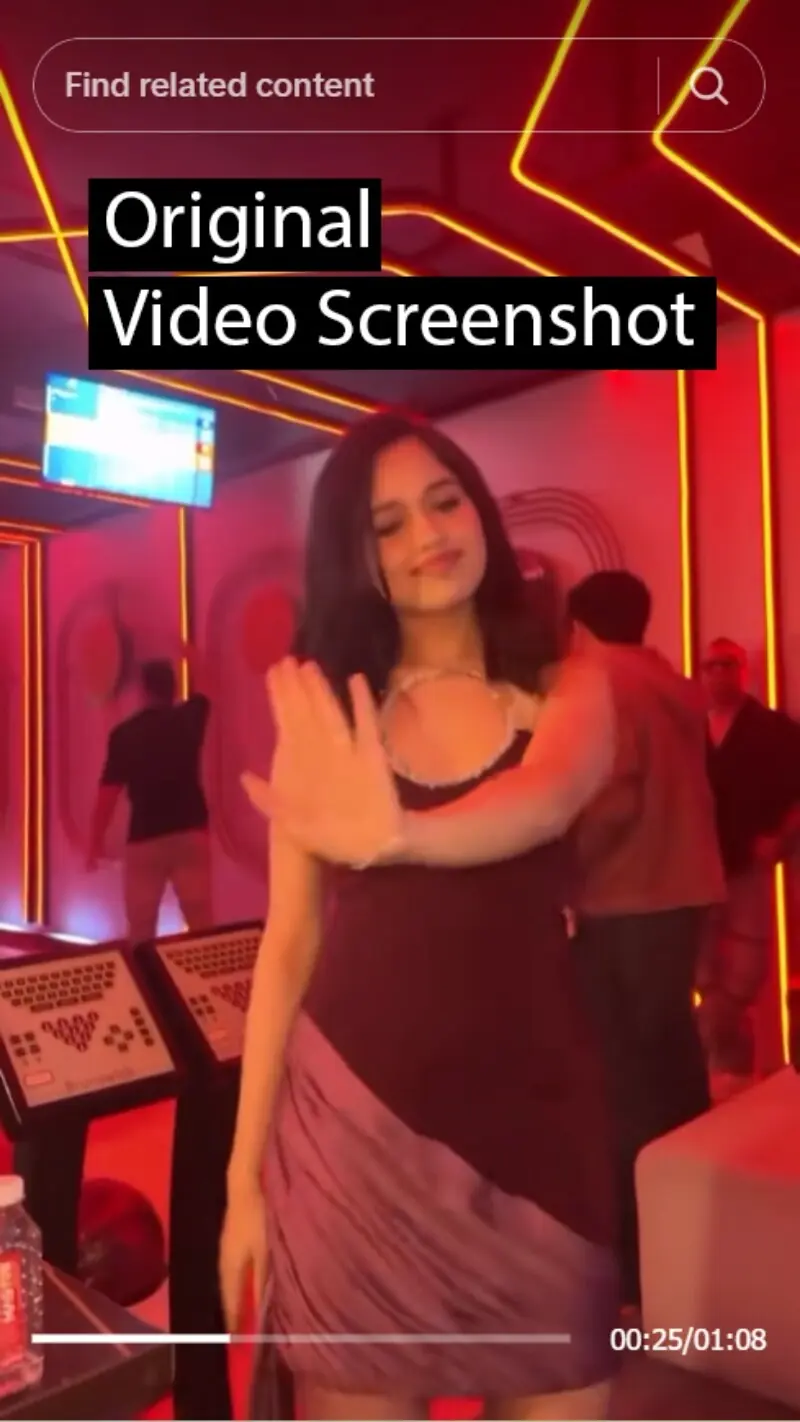

I then used Google Lens, another free online tool, to scan several screenshots of the deepfake video. The goal was to identify the source of the video and success was in sight when several search results appeared one after the other.

The body that appears in the video did not belong to Benazir Shah but to the Indian actress Jannat Zubair Rahmani: the clothes were the same, as was the lighting. The only thing the fakers had changed was their faces.

On X, Shah mentioned the deepfake video and noted that the account was followed by the government’s sitting Information Minister. That’s when the story took a strange turn. ‘PakVocals’ apologized, citing religious fear of slander. But despite the pious language, the video is still there, proving that its true intention was to damage someone’s reputation.

On November 18, another X account called ‘Princess Hania Shah’ posted a new deepfake of Benazir Shah and accused her of being a “traitor.” This deepfake edit was a lazy attempt, I thought to myself. But the intention, once again, was dangerous.

This time I didn’t even need editing software. I used Google Lens to put the fake video next to the original footage I found online. They were perfect mirrors: the same movements, the same lighting, just a different face. It took five minutes to prove it was a lie. However, more than 180,000 people had already seen it.

Fact Check: A Necessity

X, formerly Twitter, has a system called “Community Notes” designed to flag false content. But it has failed too many times. Deepfake videos still appear on the social media platform without a warning label.

What’s worse is that when users asked X’s own AI chatbot, Grok, to verify the videos, it failed to identify them as AI-generated content, revealing the limitations of billion-dollar algorithms. Simply put, we cannot trust the tech giants to protect us. If third-party fact-checkers don’t do their job, no one will.

With every passing day, fact-checking is becoming a necessity, especially in times of conflicts and wars, because AI-manipulated content is not only consumed by ordinary people but also by mainstream media.

During the recent conflict between Israel and Iran in mid-2025, a viral post on X allegedly showed analysts from an Israeli news channel fleeing their studio after an alleged attack by Iran. While the images initially looked convincing, closer inspection revealed ghostly movements, immaculate camera pans, and flat audio. But many Pakistani media outlets broadcast the clip as an authentic event.

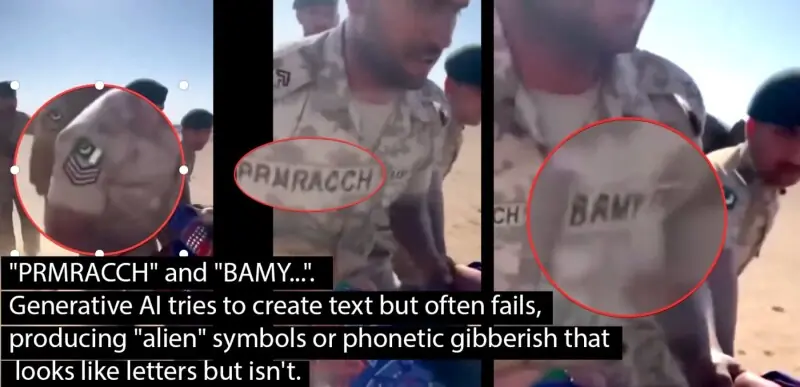

After Benazir Shah’s deepfakes, just a few hours later, I found another deepfake video. It claimed to show Pakistani soldiers abusing a Baloch woman in a desert setting. The account that posted the clip, called ‘Yousuf Bahand’, added a taunt: “Some will say this is fake.”

He was right. It’s fake!

I went back to the frame-by-frame analysis. The clues were in sight. The name tags on the soldiers’ uniforms read “PRMRACCH” and “BAMY,” a classic AI mistake when typing text, hallucinating words and producing gibberish.

The clip was also filled with other visual inconsistencies. For one thing, one of the supposed soldier’s hands in the video appeared to be fused with the woman’s hands.

Not only the video, but also the audio gave it away. When the soldier yelled “damn,” he said it with a clear American accent, nothing like what you would expect in that environment. I then ran the clip through FFMPEG, a command-line tool that converts audio or video formats.

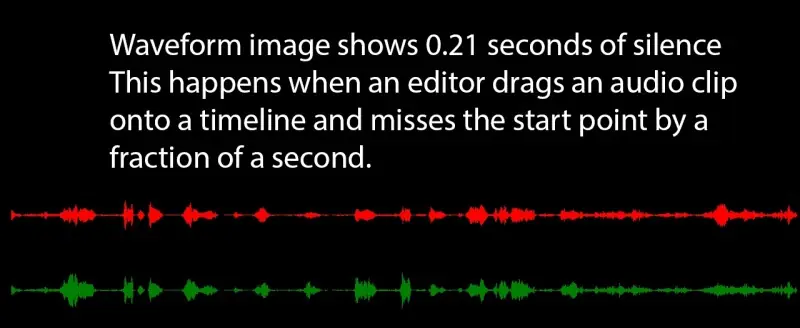

The data showed something never seen in a real desert recording: 0.21 seconds of total silence from the beginning. In an open, windy environment, the microphone always picks up ambient noise the moment it is turned on. That dead air only happens when someone pastes the audio track into the video later.

And this is not an isolated episode in which real issues are touched on. I remember, for example, the wide circulation of videos showing cows drowning during the Punjab floods of 2025. Instead of pure chaos, the videos presented a sterile calm: unnaturally still, perfectly framed, and completely lacking the expected camera shake or human sounds.

Unfortunately, most viewers seemed to stop at the initial shock of the disaster, possibly without questioning the engineers behind the synthetic content.

The ‘fall of AI’

A recent BBC investigation revealed that Pakistan has become a global hub of “AI Slop”. Creators appear to be churning out fake content, using real-world settings to spread lies, just to game algorithms and make money. The incentive is simple: Virality pays, the truth doesn’t..

Until early 2024, AI videos were mostly a buggy novelty shared by enthusiasts, but the landscape arguably changed with Sora (OpenAI), which created a sense of competition in the market with heavyweights like X’s Grok and Google’s Veo.

But to its credit, Google has just stepped in with a partial remedy: its Gemini chatbot can now flag images created with Google’s own AI tools by detecting invisible SynthID watermarks, a technology that embeds invisible watermarks on AI-generated content, such as images, audio, and text, to identify it as machine-created.

The tools I used to expose these lies are free. Anyone can use them. But unfortunately, the tools to make these lies are just as accessible. That’s the terrifying symmetry: Anyone with an ulterior motive, financial or otherwise, can invent a reality, but not everyone will have the incentive to break with those fabrications.

AI is no longer a futuristic threat. It is a street level weapon. The next viral clip you see may not be real at all, but the truth is still there beneath the distortions. You just have to slow down enough to find it. Sometimes it’s a flash on a cheek. Sometimes it’s a hand that melts. Sometimes there is silence in the waveform.

Ghosts can be unmasked, but only if we decide to look closely.

Header image created with generative AI