The last time Allen Kudlak saw his father Jacob was in August 1965. The couple hugged, then Allen approached a floating plane that took him to the residential school.

After 60 years, he finally had the opportunity to meet with his father, who is buried near the Charles Camsell hospital in Edmonton.

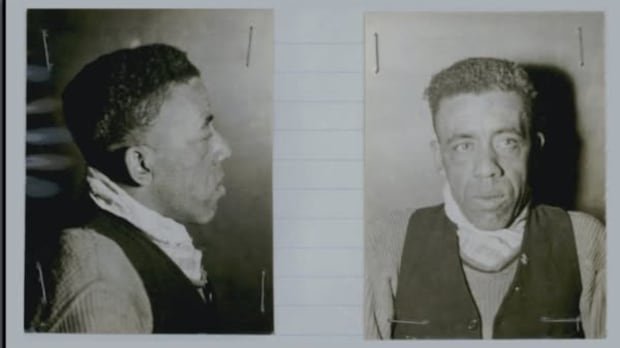

Kudlak is part of a Nunavummiut delegation this week that visited the hospital where, for decades, thousands of indigenous people were sent to receive treatment during the tuberculosis epidemic that reached its maximum point from the years 1940 to 1960. During those years, some arrived home; Many, like Jacob, no.

Nunavut Tunngikvik Inc. brought 49 Inuit from the Nunavut Kitikmeot region to the site as part of the Nanilavut initiative, a federal project dedicated to creating resources for those affected by the epidemic. That includes an Inuit database that underwent medical treatment at that time, commemorative events, monuments and compassionate trips for family members. Nanilavut, a word of Inuktitut, translates as “looking for them.”

Kudlak brought some house flowers so that his father can have a piece of Nunavut with him in his resting place. He said it is difficult to explain the feeling of relief and closing that seeing his father’s tomb, but feels lighter.

“I’ll feel better, knowing,” he said. “I will go home knowing where you are resting.”

Junna Ehaloak, another delegate, said she feels similar relief when she finds her grandfather’s tomb. She said her own father spent most of her life without knowing where her father was buried, and he died wondering.

“It’s a great relief to know,” he said. “My dad is probably full of smiles in heaven.”

Karen Nanook said the test and recognition of what families experienced is why Nanilavut’s initiative is important.

Nanook, originally from Taloyoak, spent much of his life investigating the hospital where his mother spent part of his childhood and where his uncle is buried. She said that she has not always found clear information about what happened there, and that the information she can find is sometimes incorrect, as the name of her late uncle, which she according to her was ill -written in the online records.

She said that seeing the first -hand site and having a record of those affected by the epidemic helps her face her family’s past.

“The road [my family] Handle losing their loved ones is never talking about that, “he said.” Now … they can come here and talk about their loved ones who died of TB. “

The delegates arrived during the weekend and spent Tuesday visiting the site of the old hospital and the nearby cemetery where some patients were buried. On Wednesday, the delegates participated in a commemorative banquet and a circle of healing before a closing banquet gathered everyone.