The global tide of “democratic backsliding” is forcing academics and citizens alike to confront uncomfortable truths about the system once hailed as “the best.”

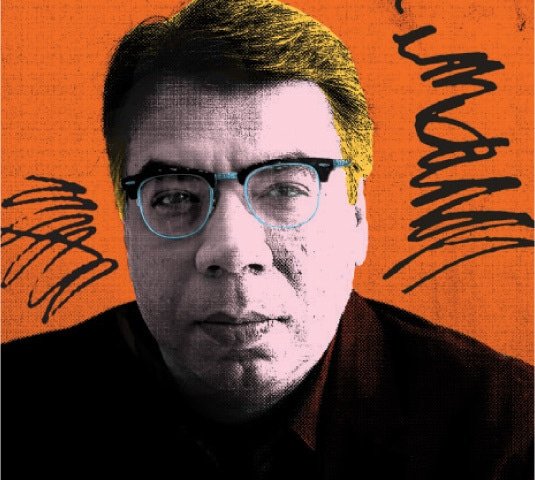

As political scientist Joel Day observed in the May 2025 issue of the Journal of Democracy, voters feel the need for change but remain deeply unsure about what that change should be. This widespread skepticism is not only fueling dissatisfaction with the democratic results but is also casting doubt on the numerous proposals put forward to halt or reverse the decline.

The central issue, it seems, lies in a fundamental disconnect between the idealized version of democracy and its lived reality. For decades after World War II, the West deeply romanticized democracy as a largely impeccable ideology, especially during the Cold War, when it was deified as the “champion” fighting Soviet communism and authoritarianism.

This sacralization meant that, while criticism of democracy was common in authoritarian states, established democracies rarely tolerated serious domestic criticism. The fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 was celebrated as a decisive victory for democracy.

However, the disastrous economic and political results of the former dictatorships that adopted democracy forced a reassessment. These systemic problems, initially attributed to the remnants of authoritarian rule, did not simply disappear. Instead, democracy collided with deeply entrenched political, economic, and social monoliths, leading to the creation of “hybrid regimes.”

Around the world, romantic expectations of democracy have collided with social realities, resulting in a pragmatic shift in which stability trumps ideals.

Countries such as Turkey, Russia, Colombia, Egypt, Indonesia, and Mexico developed hybrid forms that sometimes produced better economic and political outcomes than the idealized form of democracy.

A convenient, if increasingly rhetorical, way to lament the “suffocation of democracy” in hybrid systems is to blame an omnipresent “system” or “ruling elites.” While these factors certainly play a role, this explanation falls short when considering the paradox of public support for forces considered illiberal.

Why do more and more people, even in established democracies, agree with events that terrify “true democrats”? Consider the American context: a Change Research poll found that 42 percent of Americans support an unconstitutional third term for Donald Trump. Is this an inability of democracy to come to terms with the rapidly changing global economic landscape?

American political scientist Cas Mudde wrote about the “paradox of democracy”: the inherent tension between the democratic principle of popular sovereignty (majority rule) and the liberal principle of protecting individual rights. This conflict raises uncomfortable questions: should illiberal forces coming to power through legitimate democratic means be tolerated? Should there be constitutional checks to limit the rise of such forces? What happens when a majority of voters actively block reforms necessary for a country’s economic health?

The answer lies not only in policy, but also in psychology. As American political scientists Larry M. Bartels and Christopher H. Achen argued in Democracy for Realists, “Most voters feel more than they think.” If political decisions are based on emotions and cultural dispositions rather than logical institutional propositions, then citizen discontent will not automatically translate into acceptance of proposed procedural solutions. Social conditions, not just institutional design, are blocking reform.

In Pakistan, for example, social media and newspapers are filled with protests against the current government and the “establishment” for stifling democracy through controversial constitutional amendments. However, the alternatives suggested by critics are largely rhetorical.

The question for democracy advocates who resist these reforms must be: were the institutions these amendments attempt to reshape successful in the evolution of democracy in the country?

The answer is a resounding ‘No’.

Current institutional and political elites are proceeding with these amendments in the belief that they will provide political and economic stability by controlling factors seen as sources of tensions and chaos. Unlike past experiments, this current constitutional push is not based on grand ideology. If it has one, that ideology is pragmatism.

The crisis of democracy is a crisis of faith in its procedural solutions. When institutions fail to deliver tangible economic and political outcomes for the majority, the stage is set for a pragmatic turn: a willingness to accept outcomes that prioritize stability and effectiveness over strict adherence to an idealized, yet often ineffective, democratic procedure.

Posted in Dawn, EOS, November 16, 2025