The fossilized skull of a marine reptile called an ichthyosaur is now being studied after being found in the Kiskatinaw River Valley in British Columbia, approximately 52 kilometers south of Fort St. John.

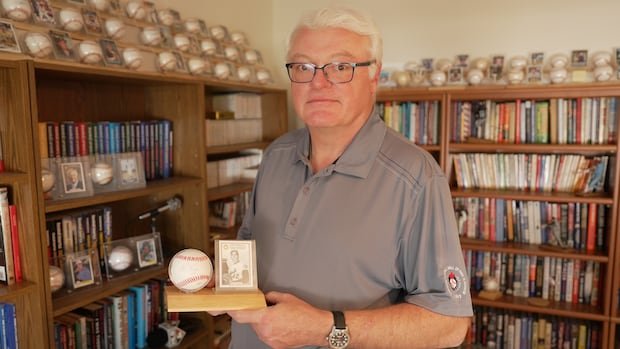

Local resident Kevin Geist and his 11-year-old son Andreas discovered the skull two summers ago, spotting a strange black rock along the river shoreline in the fossil-rich Peace region.

The Kiskatinaw River has fallen to record levels after four years of drought, meaning there are more rocks exposed there. In this case, one of those rocks contained a prehistoric skull.

“It wasn’t in the water. And that’s what makes some of these things show up now, because unfortunately we’re in a drought situation,” Geist said. “Many of the rocks are more exposed than before.”

It is a place that is believed to hold the secret not only for humanity but also for the Earth itself. Located in the Rocky Mountains, Yoho National Park is home to the Burgess Shale. Considered one of the best preserved fossil sites in the world. CBC teamed up with a paleontologist who led an expedition last summer in search of fossils of marine life dating back more than 500 million years.

Geist wasn’t sure what the rock was at first and didn’t think it was that important at first.

After returning to check out the rock this summer, Geist’s sister-in-law, Diana Hofmann, sent photographs to the Tumbler Ridge Museum.

“They showed a lot of interest, which made it exciting,” Geist added.

The Tumbler Ridge Museum Foundation has since confirmed that it is an ichthyosaur.

Ichthyosaurs are not dinosaurs, they are marine reptiles. A cross between a dolphin and a fish, they were completely adapted to an aquatic environment and gave birth to their young in the ocean.

The ichthyosaur is assumed to have died in the Triassic period, explained Eamon Drysdale, the museum’s resident paleontologist.

But Drysdale says the river valley dates back to the Cretaceous period, a time when ichthyosaurs would have been extinct, meaning the skull’s location is unusual.

The skull, which lived in a shallow sea that covered British Columbia more than 250 million years ago, was encased in Triassic carbonate rock and was most likely pushed by a glacier into the river valley after the formation of the Rocky Mountains.

“It’s been quite a journey for that one,” Drysdale said of the skull.

Fossils in the Peace region of northeastern British Columbia can date back 500 million years, Drysdale noted, and cover a good portion of Earth’s history.

“We have such a diversity of fossils,” he added.

“And for people who are just in the area looking for things or just wandering around enjoying the beautiful surroundings that we have, it’s interesting that they find specimens and fossils from a variety of different time periods.”

West Radio7:51Tumbler Ridge Museum Just Got a Rare 250 Million Year Old Ichthyosaur Fossil

Paleontologist Eamon Drysdale has been studying the ichthyosaur fossil. He is the collections manager for the Tumbler Ridge Museum.

Fossil-rich area

The Peace Region is rich in fossils and is home to numerous discoveries, including dinosaur bones, footprints, and other forms of prehistoric life.

A UNESCO World Heritage Site at Tumbler Ridge includes exhibits and trails showcasing some of those discoveries.

Drysdale says it’s hard to say if there’s anything more like the ichthyosaur skull in the valley, because of how it arrived via the glacier, but there’s a chance the low water levels could expose other fossil-bearing rocks.

“We currently haven’t explored much of that area, but I wouldn’t be surprised if there was fossil material exposed,” Drysdale said in an email.

To secure the skull safely, it was transported by helicopter to the back of a van and then driven to the museum.

Other partial ichthyosaur specimens have been recovered from Tumbler Ridge in mountainous areas, but mostly fragments of vertebrae and some skull material, Drysdale said.

He added that it is difficult to find a complete specimen, noting that the best example from the La Paz region is a shonisaurus, another marine reptile from the Triassic. It was removed from the Sikanni Chief River in 2001.

Drysdale says the recovery was a community effort, starting with the Geist family.

“We are a small local museum. Therefore, many of our reports and fossil finds come from local people,” Drysdale said.

“Everyone was great. We had a great time and are very excited to see what this specimen can tell us.”