WARNING: This story discusses suicide.

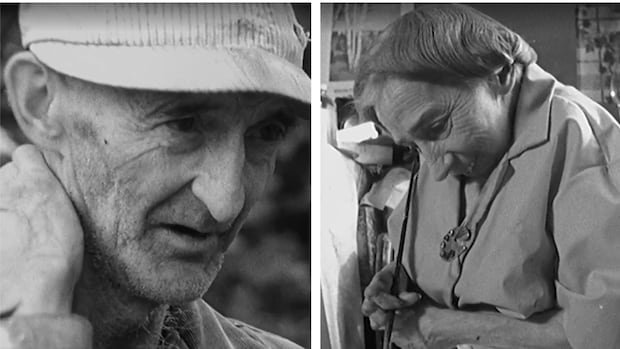

Verna Strickland was preparing for a wedding just one week before she lost a young relative with suicide.

“[He] And his friend was on the ladder, placing balloons and having fun as if nothing happened in his mind, “said Strickland.

The 13 -year -old boy in Strickland’s family died for suicide on July 7.

John Main, Nunavut’s Minister of Health, said there were three suicides for a short period of time in Mitimatalik (Pond entrance). In July, the Forensic Office of the territory said it was investigating three deaths in the community.

Strickland said the family is still suffering, but that they are managing to deal with the support they are receiving. But she said it was a loss that “nobody saw come at all.”

She describes her young relative as a fun and outgoing child, who loves hunting and was a good older brother and son.

“He was just a child with a lot of potential,” he said.

Comfort and connection after tragedies

According to a report presented in the legislature last year, 458 people in Nunavut died for suicide from 2010 to March 2024 to 451 of those deaths were among the Inuites.

Between 2014 and 2022, less than a third of those who died for suicide met with a mental health advisor or professional in the 12 months prior to their death.

And in his annual report 2023-2024, the Nunavut representative for children and young people found the 19-year-old, 19 years old, represented 23 percent of the suicides recorded in the five years that led to that report.

Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, the National Inuit organization of Canada, estimates that suicide rates in Inuit nunangat will be five to 25 times higher than the rest of Canada. In June, the Nunavut government again declared suicide a crisis in the territory.

After the suicides in July, Strickland said there was a lot of support that flowed to the community, even of charity groups such as the Canadian Red Cross and the Pulaarvik Kablu Friendship Center of Rankin Inlet.

“Pulaarvik offered not only advice but also significant activities such as rock painting, healing circles, community meetings and games. These efforts brought comfort, connection and much healing,” he said.

In the Legislative Assembly last week, Tununiq Mla Karen Nutarak said that the situation could have worsened if it were not for the interventions and resources that the Department of Health and other organizations provided.

“Several young people for advice were sent, since there were not enough resources in the community to support them all. We feared there would be more and more attempts. Several young people were put in mental health surveillance,” he said.

“While I will always be grateful for the support and resources that were provided to address the recent situation at the entrance of pond, the sad fact is still that these young lives are lost forever.”

In an interview with CBC News, Main said he cannot definitely say if tragedies at the pond entry have changed the way the government addresses suicide prevention, but has brought a new sense of urgency.

“Each consecutive tragedy serves to underline the urgency and underline the need for action,” he said.

Backed by action

Main emphasized that the work to address suicide rates in the territory is ongoing. That includes the introduction of more housing support and land programs.

He also said that RCMP has launched new efforts to educate Nunavummiut about the proper storage of firearms and medications, which is one of the steps identified in the fourth suicide prevention action plan of the territory. That is also part of a $ 5 million package, which would also include funds for the programming of the male group, which will be presented this week to debate at the Legislative Assembly.

“You can’t simply offer thoughts and sentences, it has to be backed by action,” he said.

With the Parliament back in the session, Idlout said he will be raising his concerns to federal leaders in Ottawa.

“I will express people’s concerns from today, and I will ask all the people to stay high because the Inuit are very capable, even today using our culture, our language,” he said.

“They need more support and training for advice services using Inuit qaujimajatuqangit. Helping each other, loving us, we will arrive better times.”

During a tour of some medical care facilities in Iqaluit at the end of July, the Federal Minister of Health, Marjorie Michel, said that youth suicide rates in Nunavut are a particular concern for her, and is working with the territorial government to introduce new programs for young people in smaller communities.

Strickland appreciates that there is no easy solution, but said she is tired of trying to operate in broken systems that are disconnected from the way of life Inuit.

“I will not pretend to have all the answers, but I am tired … I am tired of waiting for a change that never comes quickly enough. We are bleeding and the band’s aids are no longer enough,” he said.

“We are losing our children and we are losing our future.”

If you or someone you know are fighting, this is where to get help:

This guide of Mental addiction and health center Describe how to talk about suicide with someone who worries him.