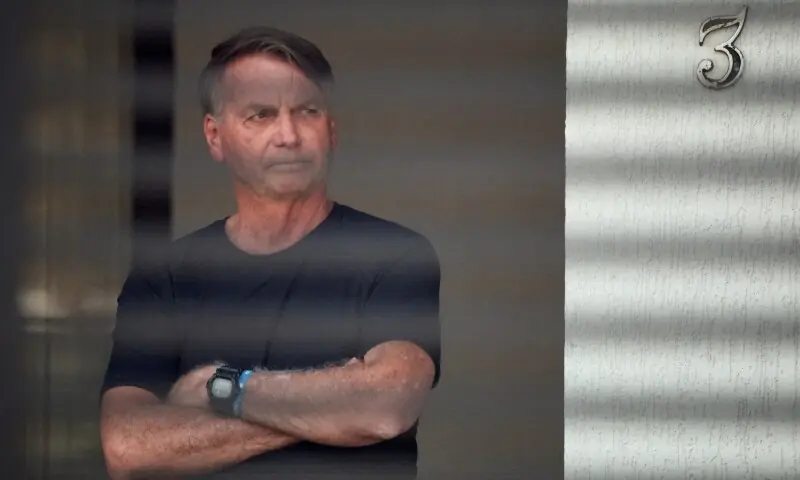

The former Brazilian president, Jair Bolsonaro, was sentenced on Thursday to 27 years and three months in prison, hours after being convicted of consigning a coup d’etat to remain in power after losing the 2022 elections, trying a powerful reprimand to one of the most outstanding populist populist leaders in the world.

The conviction ruling for a panel of five judges in the Supreme Court of Brazil, which also agreed to the sentence, turned the Bolsonaro of 70 years into the first former president in the country’s history to be convicted of attacking democracy, and caused the disapproval of the Trump administration.

“This criminal case is almost a meeting between Brazil and its past, its present and its future,” Judge Carmen Lucía said before his vote to condemn Bolsonaro, referring to a story story with military blows and attempts to overthrow democracy.

There was ample evidence that Bolsonaro, which is currently under house arrest, acted “with the purpose of eroding democracy and institutions,” he added.

Four of the five judges voted to condemn the former president of five crimes: participate in an armed criminal organization, trying to violate democracy, organize a coup d’etat and damage the property of the government and protect cultural assets.

The conviction of Bolsonaro, a former army captain who never hid his admiration for the military dictatorship that killed hundreds of Brazilians between 1964 and 1985, follows legal convictions for other extreme right -wing leaders this year, including Marine Le Pen and the Dutte of Rodrigo de France.

The near Bolsonaro, the president of the United States, Donald Trump, who had called the case a “witch hunt” and, in retaliation, hit Brazil with tariff walks, sanctions against the president judge and the revocation of visas for most of the judges of the superiors.

When asked about Thursday’s conviction, Trump praised Bolsonaro again, calling the verdict “a terrible thing.” “I think it’s very bad for Brazil,” he added.

While observing his father’s conviction from the United States, said Brazilian congressman Eduardo Bolsonaro Reuters I expected Trump to consider imposing more sanctions on Brazil and his judges of the Superior Court.

The Secretary of State of the United States, Marco Rubio, said in X that the Court had “unjustly governed”, added: “The United States will respond accordingly to this witch hunt.”

The Brazilian Ministry of Foreign Affairs issued a statement by calling Rubio’s comment a threat that “the Brazilian authority attacks and ignores the facts and the convincing evidence in the records.” The Ministry said that Brazilian democracy would not be intimidated by the United States.

President Luiz Inacio Da Silva also said that he does not fear new sanctions from the United States in an interview with the local television channel Bandhours before Bolsonaro’s sentence was confirmed.

The verdict was not unanimous, with Judge Luiz Fux on Wednesday breaking with his colleagues by absorbing the former president of all charges and questioning the court jurisdiction.

That unique vote could open a path to the challenges to the ruling, which could carry the conclusion of the trial closer to the presidential elections of October 2026. Bolsonaro has repeatedly said that it will be a candidate in those elections despite the fact that they are prohibited from running for a position.

Bolsonaro’s lawyers said in a statement that the sentence was absurdly excessive and that they would present the appropriate appeals.

From rear banks to the presidency

The conviction of Bolsonaro marks Nadir in his career from the rear banks of Congress to his forge of a powerful conservative coalition that tested the limits of the young democratic institutions of the country.

His political trip began in the 1980s at the City Council of Rio de Janeiro after a brief career as a parachute army. He became almost three decades as a congressman in Brasilia, where he quickly became known for his defense of the policies of the authoritarian era.

In an interview, he argued that Brazil would only change “the day we explode in the civil war here and do the work that the military regime did not do: kill 30,000”.

For a long time, fired as a marginal player, then refined his message to play anti-corruption issues and pro-family values.

He found fertile land when massive protests broke out in Brazil in 2014 and 2015 in the middle of the extensive graft scandal of “car washing” that involved hundreds of politicians, including President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, whose own sentence was annulled.

The anger against the establishment opened the way for its successful 2018 presidential career, with dozens of extreme right and conservative legislators chosen in their casts. They have restructured Congress in a lasting obstacle for Lula’s progressive agenda.

Bolsonaro’s presidency was marked by intense skepticism of vaccines during pandemic and a hug of illegal mining and livestock in the Amazon jungle, where deforestation rose.

While facing a tough re -election campaign against Lula in 2022, which Lula won, Bolsonaro’s comments acquired an increasingly messianic quality, which generated concerns about their willingness to accept the results.

“I have three alternatives for my future: being arrested, killed or victory,” he said, in comments to a meeting of evangelical leaders in 2021. “No man on earth will threaten me.”

In 2023, the Brazilian Electoral Court prohibited it from public office until 2030 for generating unfounded claims on the Brazilian electronic voting system.

Lula’s Institutional Relations Minister Gleisi Hoffmann said Bolsonaro’s conviction “says no one dares again to attack the rule of law or the will of people as expressed in the polls.”

Protection of democracy

The conviction of Bolsonaro and its durability will be a powerful evidence for the strategy that the highest rank judges in Brazil have adopted to protect the country’s democracy against what they describe as dangerous attacks by the extreme right.

Their objectives have included social media platforms that accused of spreading misinformation about the electoral system, as well as politicians and activists who have attacked the Court. Send the former president and his allies to jail to plan a coup reflects a culmination of that polarizing strategy.

The cases have been largely directed by the dominant figure of Judge Alexandre de Moraes, appointed for the Court by a conservative president in 2017, whose hardball approach to Bolsonaro and his allies has been held by the left and denounced by the right as a political persecution.

“They want to get me out of the political game next year,” said Bolsonaro Reuters In a recent interview, referring to the 2026 elections in which Lula is likely to look for a fourth term. “Without me in the race, Lula could beat anyone.”

The historical meaning of the case goes beyond the former president and his movement, said Carlos Fico, a historian who studies the Brazilian army at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro.

The Supreme Court also failed to condemn seven of Bolsonaro’s allies, including five military officers.

The verdict marks the first time since Brazil became a republic almost 140 years ago that military officers have been punished for trying to overthrow democracy.

“The trial is a call for attention for the armed forces,” said Fico. “They must realize that something has changed, since there was never any punishment before, and now there is.”