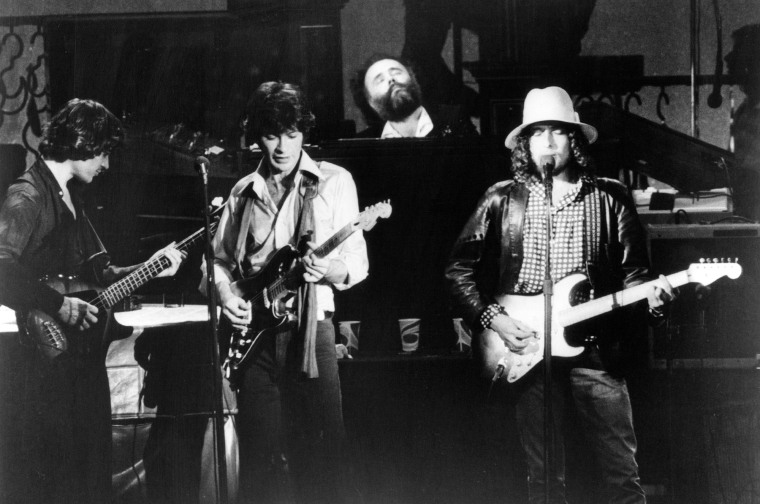

Garth Hudson, the band’s virtuoso keyboardist and multi-talented musician who drew on a unique palette of sounds and styles to add a conversational touch to rock standards like “Up on Cripple Creek,” “The Weight” and “Rag Mama Rag.” . He has died at the age of 87.

Hudson was the oldest member and last surviving member of the influential group that once backed Bob Dylan. His death was confirmed Tuesday by The Canadian Press, which cited Hudson’s friend Jan Haust. Additional details were not immediately available. Hudson had been living in a nursing home in upstate New York.

A rustic figure with a broad forehead and extensive beard, Hudson was a classically trained performer and self-taught Greek choir performer who spoke through piano, synthesizers, trumpets and his favorite Lowrey organ. No matter the song, Hudson evoked the right feeling or nuance, whether it was the boozy clavinet and wah-wah pedal on “Up on Cripple Creek,” the galloping piano on “Rag Mama Rag,” or the melancholic saxophone on “It Makes.” No Difference.” .”

Hudson, the only non-singer among five musicians celebrated for their camaraderie, texture and versatility, appeared mostly in the background, but he did have one feature: “Chest Fever,” a Robbie Robertson composition for which he devised an introductory organ solo ( “The Genetic Method”), an eclectic display of moods and melodies that gave way to the song’s hard rock riff.

Robertson, the band’s guitarist and main songwriter, died in 2023 after a long illness. Keyboardist and drummer Richard Manuel hanged himself in 1986, bassist Rick Danko died in his sleep in 1999, and drummer Levon Helm died of cancer in 2012. The band was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1994.

Formed in the early 1960s as a backing group for rocker Ronnie Hawkins, the band was originally called The Hawks and featured Arkansas-born Helm and four Canadians recruited by Helm and Hawkins: Hudson, Danko, Manuel and Robertson.

The Band mastered their craft through years of performing as unknowns: first behind Hawkins, then as Levon and the Hawks, then as unsuspecting targets of outrage after connecting with Dylan in the mid-1960s. They all joined Dylan. on his landmark tours of 1965-66 (Helm departed midway), when he broke with his folk background and joined the Band to perform some of the band’s most moving and storms of the time, which angered some longtime Dylan fans but appealed to many. the new ones. The group would change its name to Band in part because many people around Dylan simply referred to his backing musicians as “the band.”

By 1967, Dylan was in semi-reclusion, having reportedly broken his neck in a motorcycle accident, and he and the group settled into the Woodstock artist community that two years later would become world famous thanks to the festival in nearby Bethel. With no album planned, they wrote and played spontaneously in an old pink house on the outskirts of town shared by Hudson, Danko and Manuel. Hudson manned the tape machine while Dylan and The Band recorded more than 100 songs, for years available only as bootlegs, which became known as “The Basement Tapes.” Often cited as the foundation of “roots” and “American” music, the music ranged from oldies, country, and Appalachian songs to new compositions such as “Tears of Rage,” “I Shall Be Released,” and “This Wheel’s on “Fire.” “

“There was an informal discussion before every recording,’” Hudson told the online publication Something Else! in 2014. “There would be ideas floating around and stories being told. And then we went back to the songs.

“We looked for words, phrases and situations that were worth writing about. “I think Bob Dylan showed us discipline and an undying concern for the quality of his art.”

Dylan re-emerged in late 1967 with the austere “John Wesley Harding,” and the band debuted soon after with “Music from Big Pink,” their down-home sound so radically different from the then-fashionable improvisations and psychedelic tricks that artists since The Beatles even Eric Clapton of the Grateful Dead would cite his influence. The Band followed up in 1969 with a self-titled album that many still consider their best and has often been ranked among the best rock albums of all time.

Future albums included “Stage Fright,” “Cahoots” and “Northern Lights/Southern Cross,” a 1975 album that earned Hudson special praise for his keyboard work. A year later, Robertson decided he had tired of live performances and the Band organized the all-star concert and Martin Scorsese film, “The Last Waltz,” featuring Dylan, Clapton, Neil Young and many others. Tension between Robertson and Helm, who would claim that the film unduly elevated Robertson above the others, led to a complete breakup before the documentary’s release in 1978.

Hudson played briefly with the English band The Call; appeared with various later incarnations of the Gang, usually with Danko, Hudson and Helm; assisted on solo albums by Robertson and Danko; and joined Danko and Helm for a performance of Pink Floyd’s “The Wall” at the Berlin Wall. Other works from the session included records by Van Morrison, Leonard Cohen and Emmylou Harris.

Hudson also organized his own projects, although his first solo work, “The Sea to the North,” came out on the day of the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. In 2005, he formed a 12-piece band called The Best!, with his wife as voice. “Garth Hudson Presents: A Canadian Celebration of The Band” was a 2010 tribute featuring Neil Young, Bruce Cockburn and other Canadian musicians.

In recent years, Hudson had financial problems. He had sold his interest in the Gang to Robertson and went bankrupt several times. He lost a home to foreclosure and saw many of his belongings auctioned off in 2013 when he fell behind on storage payments. Hudson’s wife Maud died in 2022. They had a daughter, Tami Zoe Hill.

The son of musicians, Hudson was born in Windsor, Ontario in 1937 and received formal training at an early age. He was performing on stage and writing even before he was a teenager, although by his early 20s he had soured on classical music and played in a rock band, the Capers.

He was the last to join the Gang and was worried that his parents would disapprove. The solution was for Hawkins to hire him as a “musical consultant” and pay him an extra $10 a week.

“It was a job,” Hudson said of the Band in a 2002 interview with Maclean’s. “Play in a stadium, play in a theater. My job was to provide arrangements with pads underneath, pads and fillers behind good poets. “The same poems every night.”