The test tube carrying the Pakistan-origin wheat seeds was aboard the SpaceX Dragon Capsule, which was launched from Nasa’s Kennedy Space Centre on August 1.

Space, as all Trekkies agree, is the final frontier. It is mysterious, magnificent, mighty, and draws in earthlings who have long dreamed of exploring other worlds. In recent years, these dreams have crossed over from the realm of ambition to the reality of necessity. As billion-dollar companies and superpowers race toward the stars, a Pakistani engineer has crossed the Kármán line with nothing more than a handful of wheat seeds and a vision.

“As we speak, Pakistan-origin wheat seeds are on their way to space,” Mahhad Nayyar told Dawn.com. He and his colleague, Muhammad Haroon, successfully sent the first Pakistani payload to the International Space Station through the Kármán-Jaguar Earth Seeds for Space partnership.

The initiative brought together researchers and space leaders from four countries to explore how native crops respond to microgravity. Pakistan’s contribution, wheat seeds, was spearheaded by Mahhad.

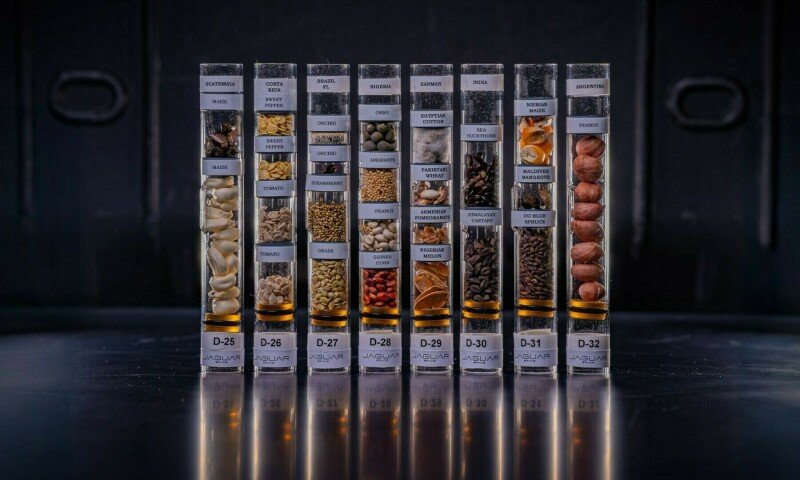

The seeds took up one-quarter of the space in the test tube, equal to the Nigerian melon seeds, Armenian pomegranate seeds, and Egyptian cotton seeds. The test tube was aboard the SpaceX Dragon Capsule — mounted on a Falcon 9 rocket — which launched from Nasa’s Kennedy Space Centre in Florida, on August 1.

“I was quite literally living a dream,” Mahhad gleamed. “Watching the rocket fire up and blaze into the sky, leaving behind a trail of smoke … all of it happened just within a few minutes. For me, though, it was the experience of a lifetime.”

But the flight from land to space, one that the 34-year-old had dreamt of for years, was long and riddled with challenges.

How it started

As a young boy, Mahhad was obsessed with the boundless horizon above him. At the time, the only way he knew to explore the skies was through flying, and, in what he describes as “quintessential fashion”, the engineer joined PAF College Sargodha, where he underwent five years of training and subsequently joined the Pakistan Air Force.

“My aim was to become a fighter pilot, but I fell short due to my short-sightedness and was hence sent towards engineering by the PAF,” he recalled to Dawn.com. In 2009, Mahhad enrolled in the aeronautical engineering programme at the PAF College, Risalpur, during which he secured a scholarship at the US Air Force Academy.

This is where his life took a turn. Mahhad went to the States with the intention of studying aeronautical engineering, but came back as an astronautical engineer. “It was here that I found my love for space; when I controlled, monitored and designed satellites.” But he couldn’t explain it to the people around him when he came back home, who thought it was a subject far-fetched, one that “didn’t even have an office here”.

For the next few years, he served as a flight engineer for search and rescue helicopters during the day and volunteered for astronomical societies in the evenings. Meanwhile, Mahhad immersed himself in the world of astrodynamics — his nights were occupied by documentaries such as ‘Cosmos: A Personal Voyage’ and ‘Cosmos: A Spacetime Odyssey’.

“I fell in love with how vast the space is. I could see all the possibilities of what could be done there,” he reminisced. As years passed by, however, he couldn’t help but wonder how Pakistan was losing out on the vast potential of the cosmos.

His disappointment further grew when, in 2020, Mahhad came across a research paper featuring a world map of countries that had participated in initiatives with the ISS. One conspicuous gap was hard to ignore: Pakistan was the only one of the world’s 10 most populous countries to not have taken part.

The image stayed with him, almost as if it were imprinted in his mind. “I realised that in two and a half decades, we were unable to send an experiment into space, let alone an astronaut. This was a matter of shame to me.” He resolved to change this and bring to life the idea that space should be accessible and meaningful for everyone, not just a select few nations or industries.

So when in 2024 he came across the Kármán Project, he knew exactly what he needed to do.

A journey into space

Mahhad applied to become a pioneer for the project, named after the line 100km above the ground from where space begins. By this time, he had retired from the PAF and was pursuing a PhD from Purdue University in the US.

“I got an email from the Kármán Project one day, wherein they were seeking proposals for sending a free-of-cost experiment to space, so I drafted a proposal with the help of my colleague Haroon, who is currently studying botany at the same varsity as mine,” he said.

Their proposal, for sending wheat seeds to space, was among the four that were accepted from across the world. These seeds, once back on Earth, will be examined at length to see the changes they underwent while in space.

“For me, just the fact that a Pakistani experiment is going to space matters the most, and the fact that we are finally on the ISS map,” Mahhad remarked. For him, it is a matter of national pride and a call to future Pakistani scientists, astronauts and aerospace engineers that nothing is beyond their reach, not even space.

The pride Mahhad talks about, he felt it the most when he visited the Kennedy Space Centre last week for the launch, making sure to keep a neatly folded Pakistani flag with him.

But Mahhad kept his excitement at bay because he knew entering the centre could be a lengthy process. It involved a lot of paperwork, and more so in his case, because Pakistan fell under the strictest criteria. A Nasa escort accompanied him throughout the visit. “Once inside, I worked with my Armenian, Nigerian and Egyptian colleagues on the final work required for the payload,” he recalled.

After a day’s delay that triggered Mahhad’s anxiety, the SpaceX Dragon Capsule finally took off from the Kennedy Space Centre’s Space Systems Processing Facility at 11:43am Eastern Time (around 8:43pm in Pakistan) on Friday and docked at the International Space Station just 15 hours after the launch.

There were many thoughts racing in his mind at the time, those of childlike wonder and pure fascination. “A rocket is essentially a controlled explosion and to put human beings on top of that and launch them to another realm of existence is not only thrilling but also leaves you in awe of how far science and technology has come for the betterment of humans.”

The science

As grand and groundbreaking as the project was, at first glance, it may seem too simple. Why wheat seeds? Isn’t that too ordinary for a space mission?

“For us, wheat seeds were a strong candidate because they’re a staple food in Pakistan and other countries,” said Haroon, the collaborator on the payload. Elaborating on the same, Mahhad told Dawn.com that the cultural and dietary significance of wheat made it a powerful symbol of sustenance, resilience and everyday life.

“Scientifically, wheat is also a strong candidate for space agriculture due to its relatively short growth cycle, high nutritional value, and adaptability to controlled environments. As space agencies explore long-duration missions and potential off-world settlements, crops like wheat will be essential to support human life sustainably,” he explained.

But most importantly, the crop serves as a bridge between nations, and while it has been studied in space before, this experiment focuses on a variety native to South Asia, cultivated in different climatic and soil conditions. Hence, both Mahhad and Haroon agreed that this could open the door to valuable comparative insights into genetic resilience and environmental adaptation under extreme conditions.

The scientific objective of the payload is to observe the effects of microgravity on the seeds. “One key focus will be on studying stomatal traits — the microscopic pores on the surface of leaves that regulate gas exchange and water loss. Stomata play a vital role in photosynthesis, respiration, and overall plant-water relations.

“By observing how these traits develop in a microgravity environment, we can better understand how space conditions may affect plant physiology at a structural and functional level. This could reveal critical insights into drought tolerance, water use efficiency, and stress adaptation,” Mahhad said.

Once the seeds come back to Earth, which is expected by the end of the month, they will be germinated under controlled conditions, and their physiological and anatomical traits will be studied.

“We will identify beneficial traits related to drought tolerance concerning stomata so these seeds won’t require extra water and will be good for both space and land. For sure they will have effect from space which will help us understand how this physiology is different from when they were sent to space,” Haroon added.

Moreover, if these traits prove to be beneficial, they could inform future breeding programmes to develop cultivars that require less water and are ideal for regions like Pakistan that are facing water scarcity or extreme climate stress. “The insights from this space-based study may help design crops that are not space-resilient but also more sustainable for vulnerable ecosystems on Earth.”

Beyond the science

But for Mahhad, the true impact of the payload goes far beyond the science behind it. Working with wheat — a staple food for millions across the globe — creates an opportunity for Pakistan and gives it a chance to connect space exploration with daily life in a way that feels intimate and real.

“It will open doors for young Pakistanis to understand, discover and fall in love with space,” he said, expressing the hope that the mission is remembered as a gentle but lasting turning point — a moment when space became a little more accessible, a little more culturally grounded, and a lot more inclusive. This also comes at a time when Pakistan, in collaboration with China, plans to send its first manned space mission to the latter’s space station

Personally, though, for Mahhad, this is just the beginning for him. A PhD student at Purdue University, Mahhad’s research revolves around space situational awareness, and his study has brought him face to face with some hard realisations.

“Emerging space economies such as Pakistan have a maximum of five objects in space; we have been unable to use the space medium adequately. Now this is not just a question of scientific exploration but also that of fundamental human equity. With developed countries now exponentially populating space with their objects, the space for countries like ours is shrinking every day.”

Mahhad wants to change this, for which Pakistan’s strategic geographical location is his biggest asset. “It is one of the best sites for looking into space traffic, and this data can be sold globally,” he said.

The benefits are not just monetary. A person going about their usual day may not even realise but space plays a huge part in their lives — from enabling smooth communication to navigating through traffic (basically Google Maps) and monitoring the climate. The benefits are endless.

“But all of this can only come through with situational awareness of the space environment,” the engineer stressed. He believes that this can only happen when Pakistan starts investing in a space programme, where students in universities, schools and colleges are encouraged to develop, launch and monitor satellites.

And to play his part, the 34-year-old plans to build a virtual mentorship lab to turn his story into a conversation starter, ultimately encouraging more experiments from Pakistan in space.

To prove his point, the engineer quotes his favourite astrophysicist and writer, Neil deGrasse Tyson: “Recognise that the very molecules that make up your body, the atoms that construct the molecules, are traceable to the crucibles that were once the centres of high mass stars that exploded their chemically rich guts into the galaxy, enriching pristine gas clouds with the chemistry of life.

“So that we are all connected to each other biologically, to the earth chemically and to the rest of the universe atomically. That’s kinda cool! That makes me smile and I actually feel quite large at the end of that. It’s not that we are better than the universe, we are part of the universe. We are in the universe and the universe is in us.”

Header image: The payload of seeds sent to space. — all photos provided by Mahhad Nayyar