A new research review of the University of Columbia Britanic (UBC) discovered that indigenous peoples experience better health results when they speak their traditional languages.

The researchers analyzed 262 academic and community studies in Canada, the United States, Australia and New Zealand, and determined 78 percent of them the vitality of indigenous language connected with better health.

Studies found positive results that varied from better physical and mental health to greater social connections and healing, to greater educational success.

A BC 2007 study revealed that youth suicide rates were reduced in the communities of the first nations, where greater amounts of people spoke indigenous languages.

“Part of the reason we did this review of the literature in the first place was because almost all of us who speak in indigenous communities who are working on the revitalization of the language report that claiming and learning their language has played an important role in their own personal health,” said co -author Julia Schillo, a doctoral student in the UBC linges department.

He made the literature review, language improves health and well -being in indigenous communities, along with a team of UBC researchers, with the help of the University of Toronto and the University of Sydney.

One of its main findings was the importance of medical care offered in an indigenous language, with adequate translation. Without that, patients ran the risk of incorrectly or misunderstood the medical instructions, and informed feeling alienation or disrespect.

In an example, Inuit children were erroneously classified as cognitive tests because their tests were in English, not Inuktitut.

The review found connections between language and well -being that is also executed more than direct communication.

For example, Schillo says that physical health improves when indigenous people participate in traditional sports and consume a traditional diet, and that both activities correlate with talking about traditional languages.

“Based on the review of literature, but also on the people I have spoken with, it has to do with how language revitalization plays in identity and feelings of belonging and connection,” he said.

“It has a lot to do with the healing of trauma and intergenerational trauma related to the Indian residential system.”

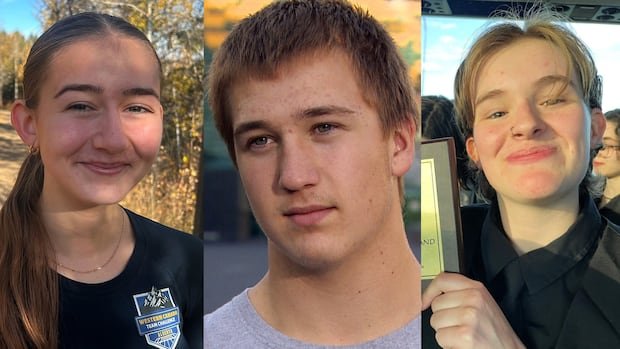

These findings are valid for Chantu William, a young language speaker Tsilhqot’in and survivor of the second generation residential school who says that learning his language growing supported his mental health and identity as an indigenous person.

William, who was not involved in the study, is a early childhood educator and a policy analyst in his nation. She is working in language manuals to give parents in the local nursery, “so that the language stays inside the house.”

She jointly developed a language curriculum with her mother, as part of the empowered young speaker program, with the cultural council of the first peoples.

William says that the idea of language manuals came from Maori relatives in New Zealand, which have a similar programming that began in the 1980s, and are speakers of strong languages.

“I feel very honored to be able to teach and learn [Tsilhqot’in] With my children in preschool and nursery and young people in my life. I feel very grateful to be in this space, in our community sharing the language. “

William says that listening to young people and the elderly speaks the language with each other happy, and that for her, “gave direction in life.”

Johanna Sam, who is also Tsilhqot’in and assistant teacher at UBC in the Department of Education, says that if governments want to support indigenous health, the revitalization of language must be part of the conversation.

“Indigenous languages are much more than words; they carry our laws, our stories and our knowledge systems that have sustained our nations since time immemorial,” he said, and pointed out that some words in indigenous languages cannot be translated into English.

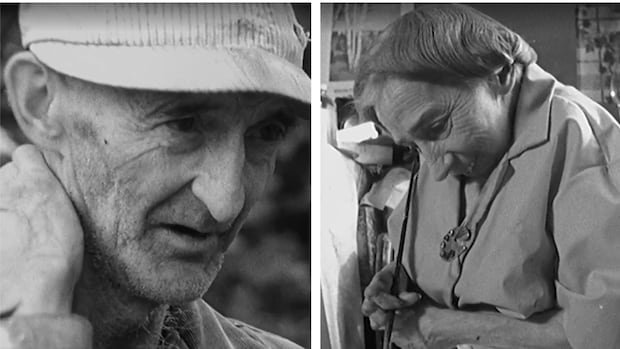

Sam says he did not have many opportunities to learn that his language was a survivor of the first generation residential school, but he grew up listening to the major generations in his family to speak it and that raised his pride and identity.

She wants to see more investment in the indigenous language curriculum and more options for medical attention to indigenous languages.

It is something that the review researchers are also asking. They are asking all levels of government to provide long -term funds for the revitalization of indigenous language and that recognize languages as a social determinant of health.