The leaders of a help organization that has sent more than 100 Haitian children with serious heart conditions to the US.

The prohibition, which comes into force on Monday, has led to generalized uncertainty for many and condemnation of international leaders. The proclamation issued on Tuesday offered exceptions to those who are legal permanent residents of the United States and those who travel to the United States for the World Cup and Olympic Games, among other examples. Such mention was not made for cases of medical necessity, such as those seeking treatment in the United States through the International Cardiac Alliance.

The total waiting list of the International Cardiac Alliance for Haitians, ranging from babies to young adults, totals at least 316 people who need cardiac surgery, said executive director Owen Robinson. Some are placed in hospitals in the Dominican Republic and occasionally in the Cayman Islands. But there are currently five open surgical spaces in the US.

“Some of them could wait a few months, and others, if they are not going now, they will die very quickly,” Robinson said.

The president’s executive order adds that the Secretary of State can issue exemptions for visas in cases that “serve a national interest in the United States.” It is not clear if the clients of the International Cardiac Alliance with medical needs conform to that description. Neither the White House nor the State Department responded to a request for comments on the matter.

“We have children who die every week waiting because there are not many international spaces for these children,” Robinson said.

Some of the children in the program travel directly from their country of origin to the United States, undergo surgery and then return to Haiti. But for many Haitians, international trips require multiple levels of logistics disputes, said Robinson. Some patients and their parents who can ensure surgeries in other countries must request a visa from the United States, travel here and then go to their eventual destination. The prohibition of travel from the United States now throws a key in that process.

Fabienne Rene, 16, was diagnosed with rheumatic heart disease in February. Due to his condition, Fabienne, who lives in Prince Port-Au, cannot even attend school, since he experiences difficulty breathing, said his father, Fignole Rene. The “bad news” he received about the prohibition of traveling that caused the postponement or possible cancellation of his daughter’s trip through the United States to the Dominican Republic is “really disturbing and breaking my heart,” he said.

“I wasn’t waiting to listen to something like that,” said Rene, 53, in Creole through a translator. “We know with certainty that there is nowhere in Haiti that we can have this possibility. The only option we have was to have an open door of the cardiac alliance.”

He also said that the news will be worrying for his family to listen and that they do not know “where they will find another open door that can give it a chance.”

Robinson said the United States embassy in Haiti recently informed him that he could probably not issue visas due to the prohibition of traveling. In the past, the Embassy has repeatedly issued visas for Haitian children to travel to the US to receive attention. The Office of the representative Becca Balint, D-Vt., Offered to communicate with the State Department to see if the children can receive exceptions, he added.

Dr. John Clark, a pediatric cardiologist at Akron’s Children’s Hospital in Ohio who has worked with Ica, said that many children in impoverished countries such as Haiti suffer from Fabienne’s condition because they are not seen by a doctor and treated by the flashing of common disease. Unre treated and recurring streptococcal infections can lead to rheumatic heart disease.

The St. Damien Pediatric Hospital in Port-Au Prince received pediatric surgical equipment from 2015 to 2019, Robinson said. Now, dangerous conditions in Haiti prevent doctors from other countries from entering or providing attention. Meanwhile, Haiti does not have enough doctors who practice there, and the loss of opportunities for medical education in Haiti only perpetuates the problem, Clark said.

Clark participated in a surgical mission there in 2019, when the visiting doctors performed two cardiac surgeries per day, he said. A drastic increase in gang violence, including an attack against one of the hospital ambulances and a worker who was stoned to death, ended most of the medical missions to Haiti.

Gang violence has only intensified since then, according to the United Nations figures, particularly after the murder of the president of Haiti, Jovenel Moïse, in 2021. Haiti is one of the poorest countries in the world, and more than half of the Haitians live under the poverty line. The country is also full of government corruption, gang violence and food insecurity, as well as vulnerability to natural disasters, including a devastating earthquake of 2010 that killed at least 220,000 people. The lack of adequate medical care also feeds diseases such as cholera, according to the Foreign Relations Council.

“I hope things can calm a day enough for us to go back there [to Haiti]”Clark said.” But at this time, there is no way to get back. “

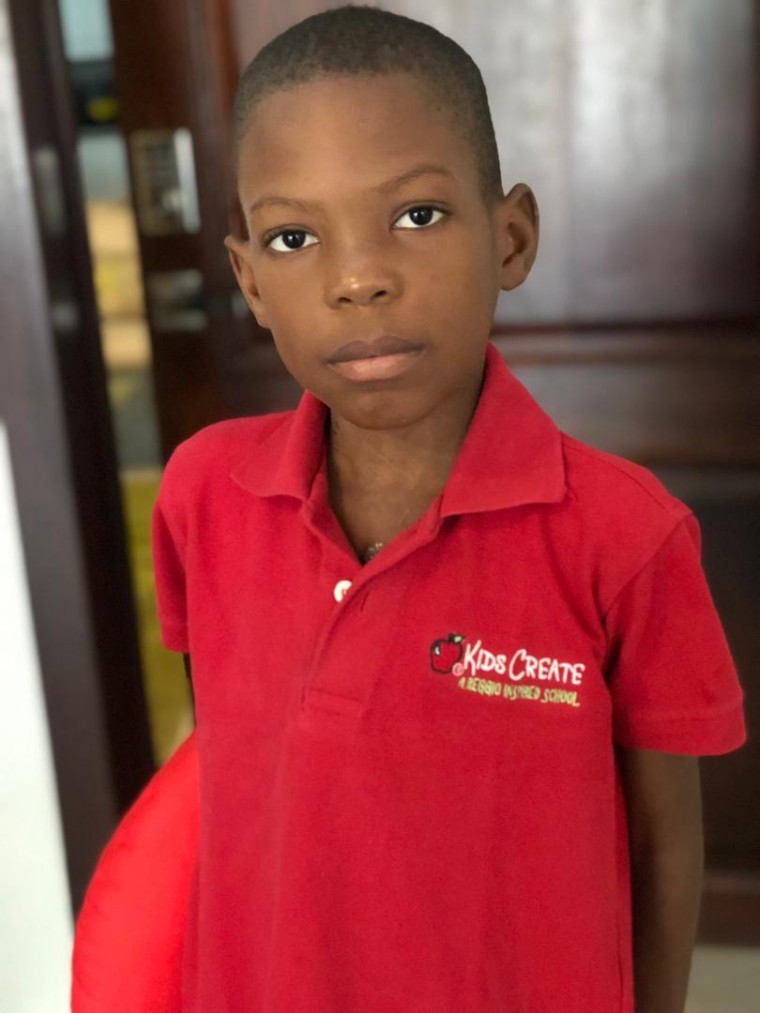

Andice Boncoeur from Port-Au Prince received free open heart surgery at the Cedimat Cardiovascular Center in the Dominican Republic To repair a valve when I was 9 years old. That procedure, however, was only destined to be a temporary solution. Now, the plans for Andrice, 16, to travel through the US for more permanent surgery have been interrupted.

On Thursday, Andice’s father, Andre Boncoeur, said he had not yet told his son about the prohibition of traveling that prevented him from going through the United States Boncoeur, said he knows “something can change at any time.”

Even so, children like Andrice do not have much time to wait. In April, Andrice was once again hospitalized for three days at the Hospitalier Eben-Ezer of the Haiti center for heart failure. Boncoeur said his family has spent “everything we had” and that his funds “have almost left.” He said he hopes that the situation changes so that his son, who aspires to become a shepherd, “can have the opportunity to live his life as a normal child.”

Clark, Robinson and the patient’s parents agree that it is the disposition of the Trump administration to accommodate sick children.

“These children are someone’s son and someone’s grandson and have no access to life’s attention,” Clark said. “Is there space for compassion?”